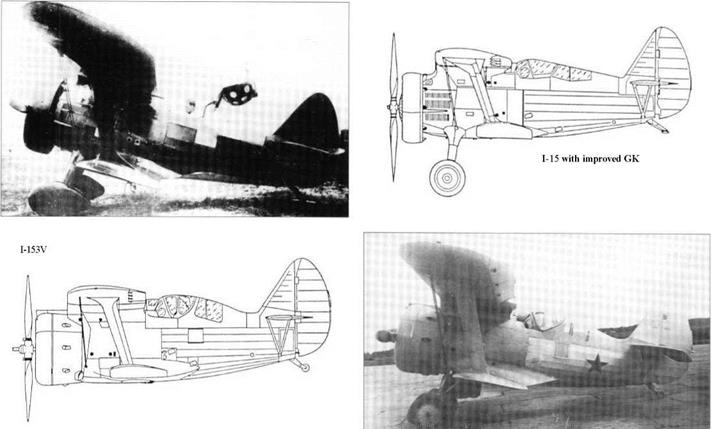

Polikarpov I-15 and I-15 3 with GK

|

|

|

Purpose: To test pressurized cockpits. Design Bureau: OSK (Department for Special Construction), Moscow, lead designerAleksei Y akovlevich Shcherbakov, and Central Construction Bureau (General Designer N N Polikarpov) where Shcherbakov also worked.

In 1935 Shcherbakov was sent to OSK to specialize in the problems of high-altitude flight. He concentrated on the detailed engineering of pressurized cockpits, called GK (Ger – meticheskaya Kabina, hermetic cabin). By this time the BOK-1 had already been designed and was almost ready to fly, but Shcherbakov did not spend much time studying that group’s difficulties. His first GK was tested on S P Korolyov’s SK-9 sailplane, predecessor of the RP-318 described previously. The second was constructed in a previously built Polikarpov I-15 biplane fighter. Polikar-

pov’s biplane fighters were noted for their outstanding high-altitude capability, and from 1938 Shcherbakov spent most of his time as Polikarpov’s senior associate. The modified aircraft first flew in 1938. Later in the same year an I-15 was tested with a very much better GK. In 1939the definitive GKwas tested on an I-153, an improved fighter whose design was directed by Shcherbakov. The test-bed aircraft was designated I-153V (from Vysot – nyi, height). This cockpit formed the basis for those fitted to MiG high-altitude fighters, beginning with the 3A (MiG-7, I-222). Later Shcherbakov managed GK design for four other OKBs, and from 1943 created his own aircraft at his own OKB.

No details have been discovered of the first GK, for the SK-9, and not many of the second, fitted to an I-15 with spatted main landing gear. Like other aircraft of the 1930s, the I-15 fuselage was based on a truss of welded KhMA (chrome-molybdenum steel) tubing, with fabric stretched over light secondary aluminium-alloy structure. Accordingly, Shcherbakov had to build a complete cockpit shell inside the fuselage, made ofthin light-alloy sheet. He had previously spent two years studying how to seal joints, and the holes through which passed wires to the control surfaces and tubes to the pressure-fed instruments. On top was a dome of duralumin,

Above right: I-153V.

Left. l – 153V cockpit.

hinged upwards at the rear. In this were set rubber rings sealing 12 discs ofPlexiglas, with bevelled edges so that internal pressure seated them more tightly on their frames. Pilots said the view was unacceptably poor, as they had done with the original BOK-1. The installation in the second aircraft, with normal unspatted wheels, was a vast improvement. Overall pilot view was hardly worse than from an enclosed unpressurized cockpit (but of course it could not compare with the original open cockpit). The main design problem was the heavily framed windscreen, with an optically flat circular window on the left and the SR optical sight sealed into the thick window in the centre. The main hood was entirely transparent and hinged upwards. Behind, the decking of the rear fuselage was also transparent. The I-153V had a different arrangement: the main hood could be unsealed and then rotated back about a pivot on each side to lie inside the fixed rear transparent deck.

Unknown in the outside world, by 1940 Shcherbakov was the world’s leading designer of pressurized fighter cockpits.