Bartini Stal’-6, El, and StaP 8

Purpose: High-speed research aircraft with fighter-likepossibilities.

Design Bureau: SNII, at Factory No 240.

One of the few aircraft designers to emigrate to (not from) the infant Soviet Union was Roberto Lodovico Bartini. A fervent Communist, he chose to leave his native Italy in 1923 when the party was proscribed by Mussolini. By 1930 he was an experienced aircraft designer, and qualified pilot, working at the Central Construction Bureau. In April of that year he proposed the creation of the fastest aircraft possible. In the USSR he had always suffered from being ‘foreign’, even though he had taken Soviet citizenship, and nothing was done for 18 months until he managed to enlist the help of P I Baranov, head of the RKKA (Red Army) and M N Tukhachevskii (head of RKKA armament). They went to Y Y Anvel’t, a deputy head at the GUGVF (main directorate of civil aviation), who got Bartini established at the SNII (GVF scientific test institute). Work began here in 1932, the aircraft being designated Stal’ (steel) 6, as one of a series of ex

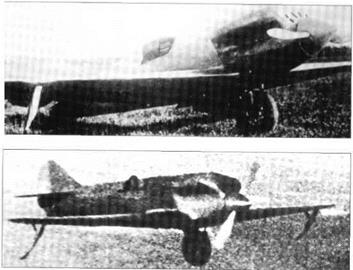

perimental aircraft with extensive use ofhigh – tensile steels in their airframes. After successful design and construction the Stal’-6 was scheduled for pre-flight testing (taxi runs at increasing speed) in the hands of test pilot Andrei Borisovich Yumashev. On the very first run he ‘sensed the lightness of the controls., .which virtually begged to be airborne’. He pulled slightly back on the stick and the aircraft took off, long before its scheduled date. The awesomely advanced aircraft proved to be straightforward to fly, but the engine cooling system suffered a mechanical fault and the first landing was in a cloud of steam. Yumashev was reprimanded by Bartini for not adhering to the programme, but testing continued. Yumashev soon became the first pilot in the USSR to exceed 400km/h, and a few days later a maximum-speed run confirmed 420km/h (261 mph), a national speed record. One of Bartini’s few friends in high places was Georgei K Ordzhonikidze, People’s Commissar for Heavy Industries. In November 1933, soon after the Stal’-6 (by this time called the El, experimental fighter) had

shown what it could do, he personally ordered Bartini to proceed with a fighter derived from it. This, the Stal’-8, was quickly created in a separate workshop at Factory 240, and was thus allocated the Service designation of I-240. Hearing about the Stal’-6’s speed, Tukhachevskii called a meeting at the Main Naval Directorate which was attended by many high-ranking officers, including heads from GUAP (Main Directorate of Aviation Production), the WS (air force), RKKA and SNII GVF. The meeting was presided over by Klementi Voroshilov (People’s Commissar for Army and Navy) and Ordzhonikidze. At this time the fastest WS fighter, the I-5, reached 280km/h. The consensus of the meeting was that 400km/h was impossible. Many engineers, including AAMikulin, designer of the most powerful Soviet engines, demonstrated or proved that such a speed was not possible. When confronted by the Stal’-6 test results, and Comrade Bartini himself, the experts were amazed. They called for State Acceptance tests (not previously required on experimental aircraft). These began

|

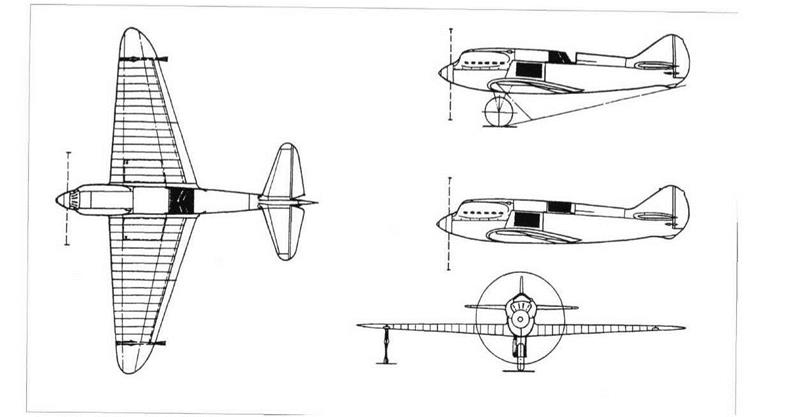

in the hands of Pyotr M Stefanovskii on 8th June 1934 (by which time the fast I-16 monoplane fighter was flying, reaching 359km/h). On 17th June the Stal’-6 was handed to the Nil WS (air force scientific research institute), where it was thoroughly tested by Ste – vanovskiy and N V Ablyazovskiy. They did not exceed 365km/h, because they found that at higher speeds they needed to exert considerable strength to prevent the aircraft from rolling to port (an easily cured fault). On 13th July the landing-gear indicator lights became faulty and, misled, Stefanovskii landed with the main wheel retracted. The aircraft was repaired, and the rolling tendency cured. Various modifications were made to make the speedy machine more practical as a fighter. For example the windscreen was fastened in the up position and the pilot’s seat in the raised position. Aftervarious refinements Stefanovskii not only achieved 420km/h but expressed his belief that with a properly tuned engine a speed 25-30km/h higher than this might be reached. The result was that fighter designers – Grigorovich, Polikarpov, Sukhoi and even Bartini himself – were instructed to build fighters much faster than any seen hitherto. Bartini continued working on the StaP-8, a larger and more practical machine than the Stal’-6, with an enclosed cockpit with a forward-sliding hood, two ShKAS machine guns and an advanced stressed-skin airframe. The engine was to be the 860hp Hispano-Suiza HS12Ybrs, with which a speed of 630km/h (391 mph) was calculated. Funds were allocated, the Service designation of the Stal’-8 being I-240. This futuristic fighter might have been a valuable addition to the WS, but Bartini’s origins were still remembered even in the mid-1930s, and someone managed to get funding for the Stal’-8 withdrawn. One reason put forward was vulnerability of the steam cooling system. In May 1934 the I-240 was abandoned, with the prototype about 60 per cent complete.

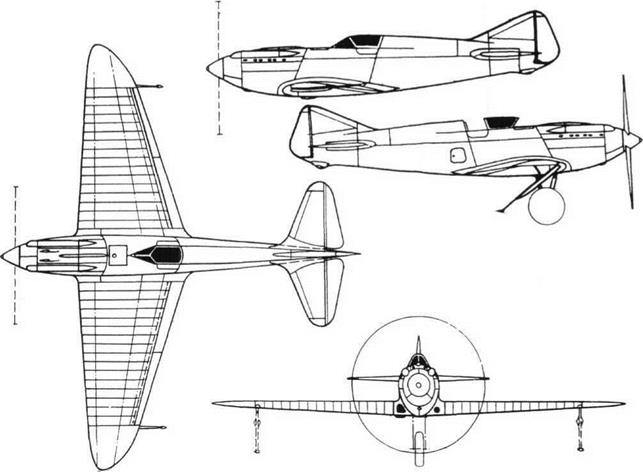

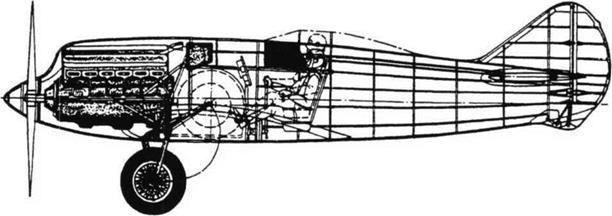

Everything possible was done to reduce drag. The cantilever wing had straight taper and slight dihedral (existing drawings incorrectly show a horizontal upper surface). The two spars were made from KhMA (chrome – molybdenum steel) tubes, each spar comprising seven tubes of 16.5mm diameter at the root, tapering to three at mid-semi-span and ending as a single tube of 18mm diameter towards the tip. The ribs were assembled from Enerzh-6 (stainless) rolled strip. Ailerons, flaps and tail surfaces were assembled from steel pressings, with Percale fabric skin. The flaps were driven manually, and when they were lowered the ailerons drooped 5°. Bartini invented an aileron linkage which adjusted stick force according to indicated airspeed (this was resurrected ten years later by the Central Aero-Hydrodynamic Institute as their

own idea). The fuselage was likewise based on a framework of welded KhMA steel tubes. Ahead of the cockpit the covering comprised unstressed panels of magnesium alloy, the aft section being moulded plywood. In flight the cockpit was part-covered by a glazed hood flush with the top of the fuselage, giving the pilot a view to each side only. For take-off and landing the hood could be hinged upwards, while the seat was raised by a winch and cable mechanism. Likewise the landing gear was based on a single wheel on the centreline, with an 800 x 200mm tyre, mounted on two struts with rubber springing. The pilot could unlock this and raise it into an AMTs (light alloy) box between the rudder pedals. For some reason the fuselage skin on each side of this bay was corrugated. The wheel bay was normally enclosed by a door which during the retraction cycle was first opened to admit the wheel and then closed. Extension was by free-fall, finally assisted by the cable until the unit locked. Under the outer wings were hinged support struts, likewise retracted to the rear by cable. When extended, each strut could rotate back on its pivot against a spring. Under the tail was a skid with a rubber shock absorber. The engine was an imported Curtiss Conqueror V-1570 rated at 630hp, driving a two-blade metal propeller with a large spinner (photographs show that at least two different propellers were fitted). This massive vee-12 engine was normally water-cooled, but Bartini boldly adopted a surface-evaporation steam cooling system. The water in the engine was allowed to boil, and the steam flowed into the leading edges of the wings which were covered by a double skin from the root to the aileron. Each leading edge was electrically spot – and seam-welded, with a soldering agent, to form a sealed box with a combined internal area of 12.37m2 (133ft2).

Each leading edge was attached to the upper and lower front tubes of the front spar. Inside, the steam, under slight pressure, condensed back into water which was then pumped back to the engine. The system was not designed for prolonged running, and certainly not with the aircraft parked.

Bartini succeded brilliantly in constructing the fastest aircraft built at that time in the Soviet Union. At the same time he knew perfectly well that the Stal’-6 was in no way a practical machine for the WS. The unconventional landing gear appeared to work well, and even the evaporative cooling system was to be perpetuated in the I-240 fighter (but that was before the Stal’-6 had flown). Whether the I-240 would have succeded in front-line service is doubtful, but it was the height of folly to cancel it. The following data refers to the Stal’-6.

|

Dimensions Span Length Wing area |

9.46m 6.88m 14.3m2 |

31 ft 14 in 22 ft 6% in 154ft2 |

|

Weights |

||

|

Empty |

850kg |

1,874 Ib |

|

Maximum loaded weight |

1,080kg |

2,381 Ib |

|

Performance |

||

|

v Maximum speed |

420km/h |

261 mph |

|

Maximum rate of climb |

21m/s |

4,135ft/min |

|

Service ceiling |

8,000 m |

26,250ft |

|

Endurance |

1 hour 30 min |

|

|

Minimum landing speed |

llOkm/h |

68.4 mph |

|