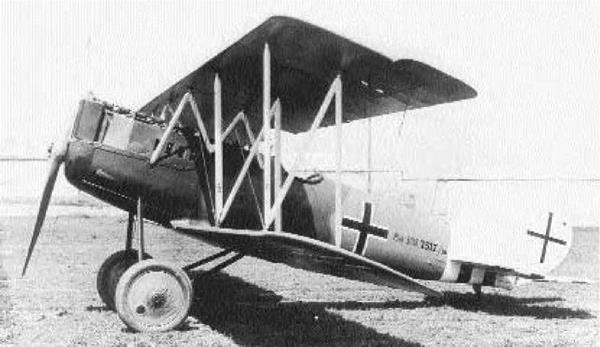

. Pfalz Dllla

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 30 feet, 10 inches; length, 22 feet, 9 inches; height, 8 feet, 9 inches Weights: empty, 1,653 pounds; gross, 2,056 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 180-horsepower Mercedes D III liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 103 miles per hour; ceiling, 17,060 feet; range, 217 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1917-1918

|

T |

he sleek-looking Pfalz D Ills were among the most streamlined fighters to appear in World War I. Its dogfighting abilities were marginally inferior to contemporary Fokkers and Albatroses, but as a balloon-buster it had no peer.

Pfalz Flugzeug-Werke of Bavaria spent the first three years of World War I building Roland D-series fighters and other craft under license. By 1917 chief engineer Rudolph Gehringer advanced plans for a new fighter possessing unmistakably sharklike lines. This new craft, the Pfalz D III, first flew in June of that year. It possessed a plywood-covered mono – coque fuselage with a sharply pointed profile. The wings were slightly staggered with single-bay struts ending in raked, pointed wingtips and mounted as close to the fuselage as possible to afford good allaround view. The lower wing was somewhat shorter than the top and featured cutouts near the roots for enhanced downward vision. The German air service greatly needed a new fighter, so construction of the D III commenced in the summer of 1917.

For all its promise, the Pfalz D III proved something of a bust in combat. Good looks notwithstanding, the plane climbed more slowly and was judged inferior in maneuverability to the contemporary Albatros and Fokker triplane fighters then in service. Yet the Pfalz was fast in level flight, possessed pleasant handling characteristics, and could outdive any German fighter extant. This trait, coupled with robust construction, made it ideal for the dangerous business of balloon-busting. Observation balloons at this time were heavily defended by artillery batteries below and were surrounded by constant fighter patrols. Thus, they were extremely difficult targets to bring down. The great strength of the Pfalz allowed it to dive upon its quarry, absorb considerable damage, and return home safely. At length, the D IIIa version was introduced, which featured minor aerodynamic refinements, including rounder wingtips and bigger tail surfaces. Nearly 600 of both models were completed, and at least 350 were in service by war’s end.

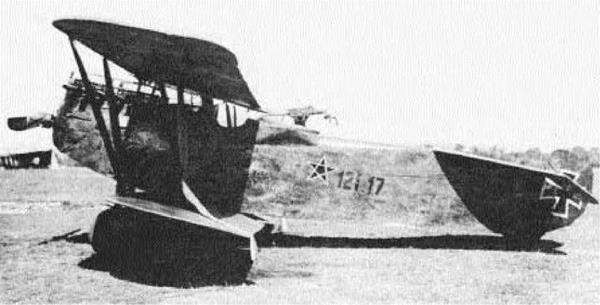

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 29 feet, 6 inches; length, 20 feet, 10 inches; height, 8 feet, 10 inches Weights: empty, 1,579 pounds; gross, 1,984 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 160-horsepower Mercedes D Ilia liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 106 miles per hour; ceiling, 18,500 feet; range, 200 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1918

|

T |

he Pfalz D XII was among the very last German fighters to appear in World War I. It was an excellent machine but always operated in the shadow of Fokker’s superb D VII.

The lackluster performance of the earlier D III fighters induced the Pfalz company to design a better high-performance aircraft as a replacement. Several intermediary prototypes were built and flown, but it was not until the Aldershof fighter trials of June 1918 that the Pfalz D XII made its unheralded appearance. The new craft showed striking resemblance to the famous Fokker D VII already in service, but it was a completely original design. Like the earlier D III, it possessed a plywood monocoque fuselage that tapered rearward to a knife’s edge. A 160-horsepower Mercedes engine was housed in a tight-fitting cowl section, with the top exposed and a radiator in front. The two-bay wings were of unequal length and heavily braced by wiring, while the top wing sported ailerons that flared out past the wingtips. But, given the applause surrounding Fok-

ker’s marvel, skeptics assumed that a few select bribes by the Bavarian government accounted for the Pfalz’s appearance. Nonetheless, several veteran pilots test-flew the craft and praised its many qualities. The government then decided to undertake production of the little-known craft to supplement the Fokkers, then in short supply.

In fact, the D XII proved an excellent design, if marginally inferior to its more famous stablemate. It was fast, immensely strong, and could outdive the D VII with complete safety. However, most pilots had their hearts set upon flying Fokkers, and when the Pfalz machine appeared at aerodromes in September 1918 pilots viewed it with disappointment and suspicion. Familiarization flights soon convinced them otherwise, and in combat it proved one of few German types able to withstand the Sopwith Camel and the SPAD XIII. The much-neglected fighter fought with distinction until the Armistice of November 1918. An estimated 200 Pfalz D XIIs had been constructed.

Type: Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet, 1 inch; length, 24 feet, 8 inches; height, 9 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 1,808 pounds; gross, 2,734 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 230-horsepower Hiero liquid-cooled engine

Performance: maximum speed, 112 miles per hour; ceiling, 17,715 feet; range, 350 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machines guns; 110 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1918-1935

|

T |

he ugly, angular Phonix C I was unquestionably the best Austrian two-seater of World War I. After a brief combat life, it capably served the Swedish air force for an additional two decades.

The advent of newer, more deadly Allied fighters toward the closing months of World War I induced Austria to seek better aircraft and replace its aging fleet of Hansa-Brandenburgs and Lohners. In the spring of 1917 the Phonix Flugzeug-Werke firm entered into competition with a rival firm, Ufag, to design the new craft. Both prototypes were based upon the Hansa-Brandenberg C I, a German two – seater of the “star-strutter” variety. When the Phonix machine emerged, it possessed unequal, positive – staggered wings with an unusual system of dual interplane vee struts. The fuselage was also very deep and placed close to the upper wing. This gave the pilot almost unrestricted frontal and upward view. Another distinctive feature was the very small rudder, which granted the gunner a near-perfect field of fire. The new craft, christened the Phonix C I, was

initially underpowered but demonstrated many useful qualities. Production commenced in the spring of 1918 following a prolonged gestation of nearly a year.

In combat, the Phonix C I proved itself one of the best warplanes of its class. Once retrofitted with a powerful, 230-horsepower motor, it exhibited excellent climbing and turning capabilities. In fact, C Is flew so well that they were easily mistaken for the single-seat Phonix D I fighter—often with fatal results. The noted Italian ace Francesco Baracca met his death at the hands of a C I tailgunner, as did scores of other unsuspecting Allied pilots. It was Austria’s fate that this fine machine served only a few months before the Armistice concluded in November 1918. A total of 110 were built.

After the war, the C I’s excellent reputation came to the attention of the newly founded Swedish air force. Between 1920 and 1932, an additional 32 C Is, known as Dronts, were built, remaining actively employed until 1935.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 32 feet, 2 inches; length, 21 feet, 9 inches; height, 9 feet, 5 inches

Weights: empty, 1,510 pounds; gross, 2,097 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 230-horsepower Hiero liquid-cooled engine

Performance: maximum speed, 117 miles per hour; ceiling, 22,310 feet; range, 217 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1918-1933

|

T |

he Phonix D I was arguably the best Austrian fighter of World War I. Slow-climbing and hard to handle, it was fast in level flight, maneuverable, and served the Swedish air force for several years.

Previously, the Phonix Flugzeug-Werke firm had been contracted to produce the Hansa-Brandenburg DI fighter under license. When it became apparent by 1917 that the infamous Star-strutter could not be developed further, the company embarked on a new aircraft. The design eventually incorporated a fuselage similar to the D I and also sported wings of unequal span that ended in rounded wingtips and swept-back leading edges. It was also considerably more powerful than the earlier machine, being propelled by a 200- horsepower Hiero engine. One interesting innovation was locating the armament within the engine cowling. This enhanced streamlining but placed the guns beyond the pilot’s reach if they jammed. The resulting craft was faster in level flight but somewhat unstable and slow-climbing. The Austrian government, hard – pressed on all fronts, nonetheless ordered the new craft into immediate production. In the spring of 1918

it entered service as the Phonix D I and was deployed with army and navy units.

The new machine was far from perfect, but it represented a dramatic improvement over the earlier Star-strutter. In capable hands the D I proved more than a match for the Italian Hanriots and SPADs. To enhance maneuverability, the new D II model introduced balanced elevators and other refinements, but the craft was judged too stable for violent acrobatics. On this basis, a few machines were fitted with cameras to pioneer single-seat high-speed reconnaissance work. Phonix then concocted the D III model shortly before hostilities concluded. It featured a more powerful engine and ailerons on all four wings, which greatly improved all-around maneuverability. The war ended before the D III could be deployed, but 158 examples of all versions were delivered.

After the war, Sweden expressed interest in obtaining several copies of the D III along with manufacturing rights. Seventeen were ultimately constructed, and they rendered useful service until 1933.

Type: Heavy Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 104 feet, 11 inches; length, 73 feet, 1 inch; height, 19 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 38,195 pounds; gross, 65,885 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 1,500-horsepower Piaggio P. XII RC35 radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 267 miles per hour; ceiling, 27,890 feet; range, 2,187 miles

Armament: 8 x 12.7mm machine guns; up to 7,716 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1942-1943

|

T |

he Piaggio P 108B was the only four-engine strategic bomber employed by Italian forces in World War II. It enjoyed performance comparable to early B-17s but was never produced in great quantity.

Italian aviation had demonstrated talent for strategic bombing, a fact clearly established during World War I. However, throughout the 1930s and until the beginning of World War II, the bulk of dictator Benito Mussolini’s bombardment assets were tied up in short-ranged twin-engine aircraft. In 1939 designer Giovanni Casiraghi attempted a more modern solution when he conceived the Piaggio P 108B (Bom – bardiere). This was an ultramodern, all-metal, four – engine aircraft similar to the famous Boeing B-17, and it was constructed for identical purposes. The P 108B housed a crew of seven and could carry a good bomb load for respectable distances. It was also heavily armed, mounting no less than eight 12.7mm machine guns. Four weapons were placed at various fuselage points, but the remaining four were ingeniously mounted in two remote-controlled barbettes atop the

outboard engines. Sighted and fired by gunners peering through transparent domes, this system anticipated by several years the system that would be utilized in Boeing B-29 Superfortresses. Despite its size, the big craft handled well in the air; it entered production in 1940. Nearly two years lapsed before the P 108B was available in squadron strength, and by that time Axis fortunes had waned considerably.

In service the P 108B proved rugged and dependable, especially when contrasted with Germany’s ill-fated He 177 Greif. It conducted several nighttime raids against Gibraltar, being fitted with flame dampeners on the exhausts. The type also performed useful service in North Africa and Russia until the Italian surrender of 1943. Beforehand, Piag – gio had also been working on a transport version of the craft, the P 108C, which featured a completely redesigned fuselage for seating 56 fully armed troops. Only 12 were built, and these were seized and used by the Luftwaffe. A total of 182 of all types were constructed.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 32 feet, 9 inches; length, 20 feet, 3 inches; height, 9 feet, 2 inches Weights: empty, 3,201 pounds; gross, 4,652 pounds Power plant: 1 x 1,000-horsepower M-62 radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 276 miles per hour; ceiling, 35,105 feet; range, 292 miles Armament: 4 x 7.62mm machine guns; up to 441 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1934-1943

|

T |

he Chaika (Gull) was among the fastest and most maneuverable biplanes ever built. It performed active duty from Spain to Mongolia before taking heavy losses in World War II.

In 1934 the gifted Soviet designer Nikolai Polikarpov, recently released from the gulag, updated his successful I 5 fighter into an even more effective craft. The new I 15 shared some commonality with its predecessor, being constructed of wooden wings, steel tubing, and fabric covering. It differed, however, in possessing an inverted gull wing that melded into the fuselage near the roots. Despite a stubby appearance, the I 15 was rugged, relatively fast, and an excellent fighter. It entered production that year, and in 1936 large numbers were sent to assist Republican forces during the Spanish Civil War. There the Chaika proved demonstrably superior to the German Heinkel He 51, and it was a formidable opponent for the supremely agile Fiat CR 32 Chirri. By 1938 I 15s were also heavily engaged against Japanese forces in Mongolia, but they suf

fered at the hands of modern Nakajima Ki 27 monoplane fighters.

Russian authorities remained convinced that biplanes were still viable weapons, so they authorized Polikarpov to update his design again. In 1937 he responded with the I 15ter, later designated the I 153, which brought biplane performance on par with monoplane opponents. With a powerful engine and retractable landing gear, it climbed faster than many of its intended adversaries. After preliminary combat in Spain during 1938-1939, large numbers of I 153s arrived in Mongolia, where, after heavy losses to both sides, they finally mastered the nimble Japanese monoplanes. Consequently, the Soviets kept the I 153 in production long after it had become obsolete. In 1941 it represented a fair portion of Russian fighter strength and sustained great losses from German Messerschmitt Bf 109s. The rugged biplane then found a new lease on life as a ground-attack craft until being replaced by Ilyushin Il 2s in 1943. A total of 3,457 Chaikas had been built.

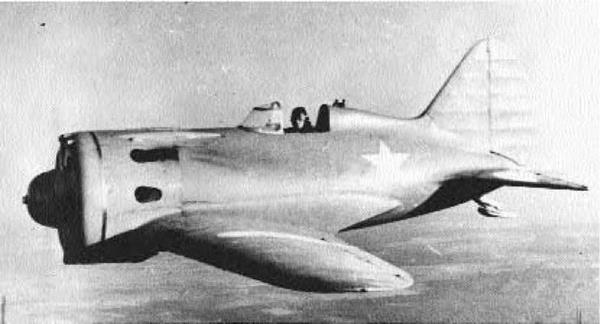

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 29 feet, 6 inches; length, 19 feet, 7 inches; height, 8 feet, 4 inches

Weights: empty, 2,976 pounds; gross, 3,781 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 775-horsepower Shvetsov M-52 radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 242 miles per hour; ceiling, 16,405 feet; range, 497 miles Armament: 4 x 7.62mm machine guns Service dates: 1935-1943

|

T |

he stubby I 16 heralded new concepts in fighter technology, becoming the first monoplane with retractable landing gear to enter squadron service. Obsolete by World War II, it gained further renown by pioneering ramming tactics.

The famous I 16 fighter evolved from attempts by Nikolai Polikarpov to wring greater performance from his already successful I 5 design. His engineers began tinkering with notions of a squat, powerful monoplane fighter, Russia’s first. The resulting prototype was extremely advanced in concept, arguably superior to any fighter in existence. The I 16 was a low-wing, cantilevered monoplane with a metal frame, a wooden monocoque fuselage, and fabric – covered wings. More important, it was the first such Russian craft with fully retractable landing gear. The I 16 was extremely fast for its day, exhibiting a 60-75 mile-per-hour advantage over biplane fighters. It also possessed an excellent roll rate and was superbly capable of climbing and zooming. However, the stubby craft proved unforgiving and somewhat

unstable along all three axes. Pilots had to carefully employ tactics emphasizing speed, not maneuverability, to survive.

I 16s were initially sent to Spain to assist Republican forces, who dubbed the little craft Mosca (Fly). It fought well enough but was never as highly regarded as the slower I 15 biplanes. I 16s were also fielded during the 1939 clash with Japan in Mongolia, rendering useful service against more nimble but slower adversaries. With international tensions on the rise, the Soviets decided to acquire large numbers of I 16s as quickly as possible. By the time production ceased in 1940, more than 7,000 had been produced, making it the most numerous fighter of the Red Air Force. In June 1941 German forces exacted a heavy toll from the obsolete I 16s, but their rugged construction was ideal for the desperate taran (ramming) attacks. Despite perils to both plane and pilot, Soviet fliers bravely adopted the new tactic, inflicting heavy damage on German aircraft. The I 16s were finally withdrawn from service in 1943.

Type: Light Bomber; Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 50 feet, 10 inches; length, 34 feet, 7 inches; height, 11 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 4,916 pounds; gross, 7,716 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 850-horsepower M-34N liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 196 miles per hour; ceiling, 28,545 feet; range, 621 miles

Armament: 3 x 7.62mm machine guns; up to 882 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1930-1943

|

T |

he R 5 was a successful multipurpose Russian design of the 1930s and superior to similar machines in the West. Rugged and fast, it gained notoriety during the Spanish Civil War under the nickname Natasha.

The year 1927 was a banner one for Nikolai Polikarpov, for he introduced two exceptionally long – serving aircraft. The first was the famous U 2, destined to be the most numerous airplane of all time. The second was the R 5, conceived as a general-purpose plane/light bomber, the first of its kind for the Red Air Force. The R 5 was an unequal-wing biplane constructed mostly of wood and was fabric-covered. It had single-bay wings fastened by “N” struts canting outward toward the wingtips. The fuselage was rather streamlined and seated a crew of two in closely spaced tandem cockpits. The craft could be fitted with either wheels or skis, and test flights revealed the R 5 to be fast and strong. It entered service in 1930; by the time production halted in 1938,

more than 6,000 R 5s had been produced. They were the most numerous aircraft of their class in the world.

In service the R 5 was possibly the best light bomber of its day. During a 1930 international airplane meet in Teheran, Persia, it easily bested such notables as the Fokker CV and Westland Wapiti in a number of categories. During this period the craft also did useful work pioneering the art of in-flight refueling. In September 1930 three R 5s flew continuously for 61 hours, landing without incident after covering 6,526 miles. In 1938 the craft was dispatched in small numbers to fight in the Spanish Civil War on behalf of Republican forces. It did useful ground-attack work, earning the affectionate nickname Natasha. R 5s subsequently formed the bulk of Soviet light attack regiments up through the German invasion of 1941. Many were destroyed in that conflict, but others simply soldiered on until being replaced by Ilyushin Il 2s in 1943.

Type: Trainer; Light Bomber; Reconnaissance; Liaison

Dimensions: wingspan, 37 feet, 4 inches; length, 26 feet, 7 inches; height, 9 feet, 10 inches

Weights: empty, 1,350 pounds; gross, 2,167 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 110-horsepower Shvetsov M-11 radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 93 miles per hour; ceiling, 10,827 feet; range, 342 miles Armament: none Service dates: 1928-

|

T |

he amazingly versatile U 2 was built in greater numbers than any other aircraft. It proved equally useful as a trainer or transport, but it won a measure of immortality as a night bomber.

In 1927 the Soviet government expressed need for a new general-purpose biplane. It was intended as their first mass-produced trainer, so the new machine had to be easy to fly, simple to maintain, and able to operate under very primitive conditions. The Polikarpov design bureau was tasked with developing such a craft, but initial efforts proved halting. The first prototype featured rectangular, austere lines, wings, and tail surfaces. When first test-flown, it failed to become airborne. Polikarpov subsequently revamped the design with rounder wingtips and single-bay configuration. The resulting U 2 was completely successful, one of the most versatile aircraft ever flown. It entered production in 1928, and by 1941 an estimated 13,000 were flying. They fulfilled a staggering variety of roles, including agricultural, civilian, ambulance, transportation, glider tug,

and parachute training duties. In 1938 a U 2 made history by locating five Soviet scientists marooned on a floating iceberg for nine months. It seemed there was little that the easy-handling biplane could not do.

The onset of World War II brought additional luster to Polikarpov’s masterpiece. Armed with bombs and small arms, they distinguished themselves as nighttime light bombers, or intruders. Flying low in the dark, the noisy U 2s dropped bombs on German soldiers to deny them sleep. Given their slow speed and great maneuverability, U 2s were also extremely hard to shoot down. When Nikolai Polikarpov died in 1943, Stalin ordered the airplane rechristened the Po 2 in his honor. By war’s end, entire regiments of Po 2 night squadrons existed, many flown exclusively by women. The little plane continued in production up until 1952, after 40,000 had been constructed. Thousands of others were exported to former Soviet satellite countries and are still in use today.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber; Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 52 feet, 6 inches; length, 35 feet, 10 inches; height, 11 feet, 9 inches Power plant: 2 x 700-horsepower Gnome-Rhone 14M radial engines Performance: maximum speed, 276 miles per hour; ceiling, 27,890 feet; range, 932 miles Armament: 5 x 7.5mm machine guns; 1,323 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1938-1942

|

T |

he Potez 63 represented a large multirole family of combat aircraft. Marginally obsolete by 1940, they suffered heavy losses and were later exported to Romania.

In 1934 the French Air Ministry issued specifications for a new two-seat fighter capable of night operations, bombardment, and reconnaissance. A special three-seat version was also desired as a “command fighter” to direct single-seat craft into action. In 1936 Louis Coroller unveiled the Potez 63 prototype to fulfill all these tasks. This was a large, all-metal airplane, one of the first “strategic” fighters then in vogue. Like its German counterpart, the Messerschmitt Bf 110, it possessed twin engines, twin rudders, and a large greenhouse canopy. After teething problems were resolved, the Potez 630 and slightly modified Potez 631s entered service in 1938. They proved to be underpowered and were retained only as trainers. But the company went on to develop the Potez 633 ground-attack version, along with the Potez 63.11 reconnaissance version. The latter model featured an extensively redesigned

nose with glazed windows and a shorter canopy moved aft along the fuselage. With 1,360 machines built in various versions, the Potez 63 series was the most numerous French design of World War II.

A Potez 63 has the distinction of being the first Allied aircraft lost in the West, when one was downed on September 8, 1939. Once the Battle of France commenced in May 1940, the Potez aircraft equipped several groupes de chasse (fighter groups) in northern France and were heavily engaged. Others saw frontline service with numerous reconnaissance outfits.

Lacking adequate fighter escort and committed to low-altitude attacks, both types suffered heavy losses. In fact, several Potez 631s were sometimes shot down by British aircraft who mistook them for Bf 110s. By the time of France’s capitulation, more than 400 machines had been destroyed. Many surviving craft were exported to Romania in time to be used against the Soviet Union in 1941. Small handfuls of Potez 63.11s were also retained by Vichy forces in North Africa, where they flew briefly against Allied forces.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 35 feet, 2 inches; length, 24 feet, 9 inches; height, 9 feet, 4 inches

Weights: empty, 2,529 pounds; gross, 3,968 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 645-horsepower Bristol Mercury VIS radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 242 miles per hour; ceiling, 26,250 feet; range, 435 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns

Service dates: 1935-1939

|

W |

hen it first appeared in 1935, the Jedenastka was arguably among the world’s finest fighter planes. Four years later this distinctive craft was flown with great skill and courage in the defense of Poland.

For many years the fledgling Lotnictowo Wo – jskowe (Polish air force) groped with imported and usually mediocre aircraft. However, in 1929 Zygmunt Pulawski, a brilliant young designer working at the National Aircraft Factory (PZL), conceived a unique, parasol-winged fighter design, the P 1. This was followed two years later by the P 7, which was high – powered, constructed entirely of metal, and covered by stressed skin. Its introduction pushed Poland to the forefront of aviation technology at a time when most Western powers were still designing fabric-covered biplanes. In 1931 Pulawski, before his death in a plane crash, began designing an improved version of the P 7, which became known as the P 11. It enjoyed a more powerful engine and numerous aeronautical refinements that rendered it an even better airplane

than the P 7. The P 11, affectionately known by pilots as the Jedenastka (Eleventh) was ruggedly built, fast for its day, and outstandingly maneuverable. It was so impressive that Romania purchased 50 machines outright and applied for a license to construct them. However, within a few years these world-famous gull-wing wonders were overtaken by low-wing monoplane aircraft—most notably Germany’s Messerschmitt Bf 109—and rendered obsolete.

By the advent of World War II in September 1939, the PZL P 11s constituted the bulk of Poland’s first line of defense. Polish pilots, seemingly helpless in the face of modern opposition, proved fanatically brave in defending their homeland. In fact, the first German aircraft shot down in World War II fell to the guns of a P 11 on September 1, 1939. Although ultimately overrun, these brave aviators managed to claw down 124 German aircraft with a loss of 114 P 11s. Of the 258 Jedenastkas constructed, one survives in Warsaw and is displayed as a cherished symbol of national resistance.

Type: Light Bomber; Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 45 feet, 9 inches; length, 31 feet, 9 inches; height, 10 feet, 10 inches

Weights: empty, 4,251 pounds; gross, 7,771 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 680-horsepower Bristol Pegasus VIII radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 199 miles per hour; ceiling, 23,950 feet; range, 783 miles

Armament: 3 x 7.7mm machine guns; up to 1,543 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1937-1939

|

T |

he Karas was another formerly advanced Polish machine that had fallen behind technologically by 1939. Flown with fanatical bravery, they inflicted heavy losses upon German armored formations.

In 1931 the Polish government sought to acquire a new light bomber based upon the unsuccessful PZL P 13 civilian transport. Several prototypes were then constructed until the cowling was lowered somewhat to improve the pilot’s forward vision. This change gave the new P 23 Karas (Carp) its decidedly humped appearance. It was an allmetal machine with fixed, spatted landing gear and a spacious glazed canopy. The P 23 also mounted a bombardier/tailgunner’s ventral gondola just aft of the main wing. At the time it debuted, the Karas possessed radically modern features such as stressed skin made from sandwiched alloy/balsa wood. This innovation conferred great strength and light weight to the machine. Initial production models were powered by a 590-horsepower Bristol Pegasus radial engine, but their performance proved lim

ited and they served as trainers. Subsequent models featured more powerful engines and greater payload, entering frontline service in 1937. By 1939 P 23s equipped 12 bombing and reconnaissance squadrons in the Polish air force. Bulgaria also expressed interest in the P 23, purchasing 12 and ordering an additional 42 in 1937. Nonetheless, by the eve of World War II the Karas had become outdated as light bombers and helpless in the face of determined fighter opposition.

The initial German blitzkrieg of September 1, 1939, failed to destroy many P 23s on the ground, and they struck back furiously at oncoming armored columns. Several Panzer forces lost up to 30 percent of their equipment in these raids, although many P 23s were claimed by ground fire and enemy fighters. Toward the end of the month-long campaign, a handful of surviving Karas fought their way to neutral Romania. Within two years these machines were reconditioned and flown against the Soviet Union. A total of 253 were built.

Type: Medium Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 58 feet, 8 inches; length, 42 feet, 4 inches; height, 16 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 9,293 pounds; gross, 19,577 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 925-horsepower Bristol Pegasus radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 273 miles per hour; ceiling, 19,685 feet; range, 1,616 miles Armament: 3 x 7.7mm machine guns; up to 5,688 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1938-1939

|

T |

he Los (Elk) was a world-class attack bomber and Poland’s most formidable air weapon of World War II. It arrived in only limited quantities but nonetheless performed heroic work throughout a hopelessly lopsided campaign.

The amazing P 37 Los had its origins in the experimental P 30 civilian transport of 1930, which failed to attract a buyer. That year a design team under Jerzy Dabrowksi conceived a modern bomber version of the same craft and proffered it to the government in 1934. A prototype was then authorized, first flying in 1936. The P 37 marked a pinnacle in medium bomber development for, in terms of design and performance, it was years ahead of contemporary machines. This was a sleek, all-metal, low-wing monoplane employing stressed skin throughout. Although relatively low-powered, its broad-chord wings permitted amazing lifting abilities, and it could hoist more than 5,000 pounds of bombs aloft—the equivalent of half its own empty weight! No medium bomber in the world—and few heavy bombers for that matter—could approach such per

formance. The Los entered production in 1937, and the first units became operational the following year. The government originally ordered 150 machines, but resistance from the Polish High Command, which viewed medium bombers as expensive and unnecessary, managed to reduce procurement by a third. Meanwhile, other countries expressed great interest in the P 37, with Bulgaria, Turkey, Romania, and Yugoslavia placing sizable orders. A total of 103 machines were built.

By the advent of World War II in September 1939, the Polish air force could muster only 36 fully equipped P 37s. Several score sat available in waiting but lacked bombsights and other essential equipment. Nonetheless, the Los roared into action, inflicting considerable damage upon advancing German columns. When the outcome of the fight became helpless, around 40 surviving machines fled to neutral Romania and were absorbed into its air force. Within two years these fugitives were reconditioned and flown with good effect against the Soviet Union.