. Myasishchev M 4 Molot

Type: Strategic Bomber; Tanker; Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 174 feet, 4 inches; length, 169 feet, 7 inches; height, 46 feet, 3 inches

Weights: empty, 166,975 pounds; gross, 423,280 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 20,944-pound thrust Mikulin RD-3M-500Aturbojet engines

Performance: maximum speed, 620 miles per hour; ceiling, 44,950 feet; range, 7,705 miles

Armament: 8 x 23mm cannons; up to 19,842 pounds of nuclear weapons

Service dates: 1956-

|

T |

he impressive M 4, often touted as “Russia’s B-52,” was in fact a strategic white elephant. Incapable of bombing the United States, they found useful employment as tankers and reconnaissance craft.

Vladimir M. Myasishchev was a senior engineer with the Petlyakov design bureau until the end of World War II, when he was summarily told to retire. Having prior experience with the Soviet gulag system, he dutifully slipped into obscurity to teach aeronautics until 1949, when Stalin personally ordered him to create his own design bureau. Mya – sishchev suddenly found himself tasked with creating a huge intercontinental jet bomber capable of dropping atomic bombs on the United States and returning safely! Given the primitive nature of jet technology at that time, the Tupolev rival firm opted to utilize turboprop engines instead. However, Myasishchev performed as ordered, and in 1954 the prototype M 4 Molot (Hammer) made its dramatic appearance during the annual May Day flyover. It was a sight calculated to send shivers down the spines of

Western observers. The M 4 was huge, possessed swept wings and tail surfaces, and mounted four gigantic Mikulin turbojet engines buried in the wing roots. By 1956 around 200 of the giant craft had been delivered and constituted the bulk of Soviet strategic aviation. For many years thereafter, U. S. defense experts strained over the prospect of countering the Soviets’ intimidating “B-52.” NATO code named it BISON.

In reality, the M 4 possessed only half the thrust and range of Boeing’s B-52, a true intercontinental bomber, and was scarcely a strategic threat. The Soviets understood this perfectly and continued building seemingly obsolete Tu 95 turboprop bombers for many years thereafter. By the 1960s the aging Myasishchev giants were employed only as tankers and maritime reconnaissance craft. One example, the VM-T Alant, was given twin rudders and employed to haul oversized parts for the Soviet space program. A few M 4s remain in service as test vehicles. Literally—and figuratively—the massive Molot was a big failure.

Type: Torpedo-Bomber; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 48 feet, 10 inches; length, 34 feet; height, 12 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 6,636 pounds; gross, 11,464 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,800-horsepower Nakajima Mamoru radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 235 miles per hour; ceiling, 27,100 feet; range, 1,237 miles

Armament: 1 x 7.7mm machine gun; 1,764 pounds of bombs or torpedoes

Service dates: 1938-1945

|

T |

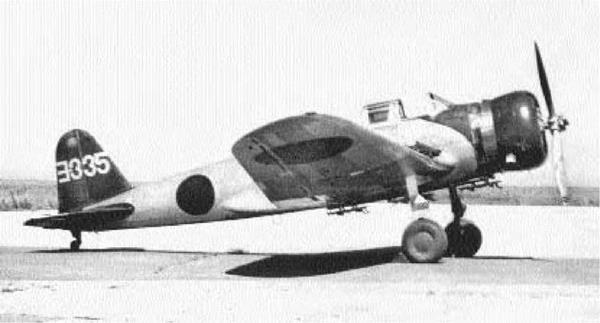

he stately B5N was the world’s best carrier – based torpedo-bomber during the initial phases of World War II. Although somewhat outdated, it sank several thousand tons of U. S. warships.

In 1935 the Imperial Japanese Navy sought quantum improvement in its torpedo-bombers, issuing specifications for a new all-metal monoplane. The new craft had to reflect stringent requirements: less than 50 feet in wingspan, capable of carrier storage, with at least four-hour endurance fully armed. The following year a Nakajima design team under Katsuji Nakamura conceived the B5N, which first flew in 1937. It was a low-wing monoplane with stressed skin and a long greenhouse canopy housing three crew members. It also possessed widetrack landing gear for ease of landing, and had extremely smooth lines. The B5N proved somewhat underpowered but entered production the following year. They performed well against weak Chinese defenses as a light bomber, but clearly a stronger engine was needed. By 1939 new versions with the Sakae 11 radial engine were produced, with little overall im

provement. However, the gentle-handling B5N, once teamed with the Long Lance torpedo, a notorious shipkiller, was a weapon of great potential. At the onset of the Pacific war in December 1941, B5Ns formed the core of elite Japanese carrier aviation. They received the Allied code name Kate.

The deadly effectiveness of the B5N was underscored during the attack on Pearl Harbor when 146, flying as light bombers and torpedo craft, sank eight U. S. battleships. Thereafter, in a succession of naval engagements that ranged throughout the eastern Pacific, Kates were responsible for sinking or severely damaging the carriers USS Lexington, USS Yorktown, and USS Hornet by October 1942. But Japanese forces were severely pummeled in these affairs, and the Americans slowly acquired air superiority with better fighters. Thereafter, Kates became easy targets and suffered severe losses until 1944, when they finally withdrew from frontline service. Several were then fitted with radar and performed antisubmarine patrols until the war’s end.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 48 feet, 10 inches; length, 35 feet, 7 inches; height, 12 feet, 5 inches Weights: empty, 6,636 pounds; gross, 12,456 pounds Power plant: 1 x 1,850-horsepower Mitsubishi MK4T Kasei radial engine Performance: maximum speed, 299 miles per hour; ceiling, 29,660 feet; range, 1,085 miles Armament: 1 x 7.7mm machine gun; 1 x 12.7mm machine gun; 1 x 1,764 pound torpedo Service dates: 1944-1945

|

T |

he rugged Jill, as it was known to the Allies, was a tardy entry to World War II intended to replace the earlier and more famous Kate. A capable machine, it was continually beset by engine problems and inexperienced crews.

By 1939 the Imperial Japanese Navy realized that a replacement of the aging B5N torpedo-bomber was becoming a military necessity. The naval staff then approached Nakajima and suggested a new craft, based upon existing designs, that would employ the widely manufactured Mitsubishi Kasei radial engine. The ensuing B6N was then developed by Kenichi Mat – sumura, who took the liberty of powering it with the company’s new and untested Mamoru engine. This airplane showed strong family resemblance to the B5N and sported its big engine in an oversized cowling. Another unique feature was the oil cooler, which was offset to the left so as not to interfere with torpedolaunching. Tests revealed the plane to be faster than the old Kate but less easily handled. Furthermore, the B6N suffered from prolonged development because

the Mamoru engine vibrated strongly and tended to overheat. It was not until 1943 that these teething problems were resolved and the B6N could enter production as the Tenzan (Heavenly Mountain). The B6N was superior in some technical aspects to the Grumman TBF Avenger and Fairey Barracuda, but by then the Japanese navy was in dire straits.

The B6N, code named Jill, was a fine torpedo platform, but it was deployed at a time when the Americans enjoyed total air superiority. Moreover, sheer size restricted it to operating from the biggest carriers, and it frequently went into battle bereft of fighter escort. Consequently, in a succession of battles ranging from Bougainville to Okinawa, most B6Ns were shot down before ever reaching their targets. Once all Japanese carriers were lost, they were further restricted to operating from land bases. By 1945 the tide of war had inexorably turned in America’s favor, and many Jills were converted and flown as kamikazes. A total of 1,133 of these formidable machines were built.

Type: Reconnaissance; Night Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 55 feet, 8 inches; length, 39 feet, 11 inches; height, 14 feet, 11 inches

Weights: empty, 10,670 pounds; gross, 18,043 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 2,260-horsepower Nakajima NK1F Sakae radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 315 miles per hour; ceiling, 30,580 feet; range, 2,330 miles

Armament: 4 x 20mm cannon

Service dates: 1943-1945

|

T |

he J1N1 was a lumbering, unspectacular machine but did useful service as a high-speed reconnaissance craft. It was later crash-converted into a night fighter but flew too slowly to impact B-29 raids.

The ongoing war with China convinced Japanese naval officials of the need for a strategic fighter capable of escorting long-range bombers. By 1938 they could point to the French Potez 63 and German Me 110 as examples of what then seemed a promising new technology. Specifications were then issued for a three-seat aircraft possessing tremendous range and firepower while retaining maneuverability equal to single-seat fighters. Kat – suji Nakamura of Nakajima conceived such a craft that first flew in 1941. Called the J1N1, it was a big twin-engine fighter with a low wing and a two-step fuselage to accommodate a pilot, observer/naviga- tor, and tailgunner. Another unique feature was the remote-controlled twin barbettes mounting four machine guns. In flight the big craft demonstrated good speed and handling, but it was in no way com

parable to a fighter. The navy then decided to strip it of excess equipment for use as a high-speed reconnaissance craft. Thus, in 1943 the J1N1 entered service as the Gekko (Moonlight); Nakajima manufactured 477.

The Gekko was first encountered during the later phases of the Solomon Islands campaign and failed to distinguish itself in its appointed role. The Americans, who perceived it as a fighter of some kind, bestowed the code name Irving. At length Commander Yasuna Kozono of the Rabaul garrison suggested fitting the big craft with oblique 20mm cannons to operate as a night fighter. Several aircraft were so modified and enjoyed some success against B-24 Liberators. Consequently, the majority of J1N1s were retrofitted to that standard. The fuselages were cut down to accommodate two crew members, and they were fitted with 20mm cannons and AI radar. Most Irvings flew in defense of the homeland but lacked the speed necessary to engage high-flying B-29s. Consequently, most spent their final days employed as kamikazes.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 37 feet, 1 inch; length, 24 feet, 8 inches; height, 10 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 2,447 pounds; gross, 3,946 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 710-horsepower Nakajima Ha-1otsu radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 265 miles per hour; ceiling, 40,190 feet; range; 389 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.7mm machine guns

Service dates: 1937-1945

|

T |

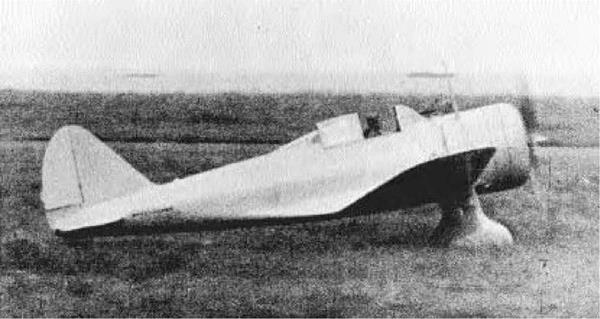

he lithe and comely Ki 27 was quite possibly the most maneuverable fighter plane of all time. It was built in greater quantities than any other Japanese prewar aircraft.

As in Italy, Japan’s predilection for maneuverability in fighter craft outweighed all other tactical considerations. In 1935 the Imperial Japanese Army announced specifications for its first monoplane. Of three contenders, the Nakajima design triumphed based on its startling agility. It was an all-metal, low – wing aircraft employing stressed aluminum skin and flush-riveting. It also featured streamlined, spatted landing gear and the army’s first fully enclosed canopy. The machine was also extremely compact, representing—literally—the smallest fuselage and biggest wing that could be designed around a Nakajima Kotobuki radial engine. Flight tests revealed it was highly responsive and even more acrobatic than existing Japanese biplanes. It was also somewhat slower than comparable Western machines, a fact that maneuver-oriented Japanese pilots chose to ignore. In 1937 the new machine entered into service

as the Ki 27. During World War II Allied intelligence assigned the code name Nate.

No sooner had Ki 27s arrived in China than they swept the skies of outdated Chinese aircraft. In 1939 fighting also flared up between Japan and the Soviet Union along the Mongolian border. Ki 27s saw much hard fighting against Polikarpov I 15 biplanes, usually with good results, but they were at a disadvantage when opposing faster I 16 monoplanes. To improve pilot vision, later models had a cut-down canopy. Production ceased in 1940 after a run of 3,999 machines. When the Pacific war commenced in 1941, Ki 27s were conspicuously engaged at Malaysia, the Philippines, and Burma. They easily mastered obsolete Allied machines in those theaters but were less successful against faster Curtiss P-40s of the Flying Tigers. After 1942 Nates were withdrawn from frontline service in favor of the more modern Ki 43 Hayabusas. Most were relegated to training and home defense squadrons, but after 1945 many surviving Ki 27s were impressed into kamikaze service.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 35 feet, 6 inches; length, 29 feet, 3 inches; height, 10 feet, 8 inches Weights: empty, 4,211 pounds; gross, 5,710 pounds Power plant: 1 x Nakajima Ha-115 radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 329 miles per hour; ceiling, 36,745 feet; range, 1,988 miles Armament: 2 x 12.7mm machine guns; 551 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1941-1945

|

T |

he nimble Ki 43 was the most numerous Japanese army fighter despite an inherently limited design potential. Rendered obsolete by modern Allied fighters, it remained in frontline service to the bitter end of World War II.

In 1938 the Imperial Japanese Army staff began considering a replacement for the Nakajima Ki 27 fighter and asked Nakajima to comply. As before, they sought an aircraft with peerless maneuverability, even at the expense of speed, firepower, and pilot protection. A design team under Hideo Itokawa advanced plans for a craft based upon the Nakajima Ki 27, one that was thinner and possessed retractable landing gear. It was a handsome, low-wing monoplane of extremely light construction, but it was rather low-powered. Subsequent modifications included bigger wings and combat “butterfly flaps” that greatly enhanced performance and handling qualities. One notable weakness was the armament that, to save weight, was restricted to two rifle-caliber machine guns. Nevertheless, the Ki 43 entered the service in late 1941 as the Hayabusa (Peregrine Fal

con), possibly the most maneuverable fighter in history. Only 50 Ki 43s were on hand when the Pacific war broke out in December 1941. They nevertheless proved quite an unpleasant surprise to the unsuspecting Allies, who christen it the Oscar.

The Ki 43 debuted during the successful Japanese conquest of Singapore and Burma and swept aside all the Hawker Hurricanes and Brewster Buffaloes it encountered. They had tougher going against Curtiss P-40s of the Flying Tigers, which refused to engage them in a suicidal contest of slow turns. Soon it became apparent that newer and more powerful versions of the fighter were needed, so the Oscar II employed a larger engine, two 12.7mm machine guns, and a three-blade propeller. These new versions retained all of the Hayabusa’s legendary maneuverability. However, by 1943 they were hopelessly outclassed in the face of new and better Allied machines. Lacking a replacement, Oscars remained in frontline service until 1945, the most numerous Japanese army fighter of the war. Production peaked at 5,919 machines.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 31 feet; length, 28 feet, 10 inches; height, 10 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 4,614 pounds; gross, 6,598 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,520-horsepower Nakajima Ha-109 radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 376 miles per hour; ceiling, 36,745; range, 1,056 miles

Armament: 2 x 12.7mm machine guns; 2 x 20mm cannon

Service dates: 1942-1945

|

L |

ike the J2M Jack, the Ki 44 was one of few Japanese aircraft designed specifically as an interceptor. It acquired limited success in that role but never enjoyed much popularity among its pilots.

In 1939 the Imperial Japanese Army staff broke with tradition by agitating for interceptor fighters that placed speed and climb over time-honored qualities of maneuverability. Nakajima complied with a prototype somewhat based upon its Ki 43 Oscar, which made its maiden flight in August 1940. The new machine, the Ki 44, was a low-wing monoplane as before, but it possessed stubby wings and a bulbous cowling over a large Nakajima Ha-41 radial engine. It was also heavily armed, carrying two light and two heavy machine guns. Flight tests proved that the Ki 44 climbed faster and higher than any Japanese fighter extant. In 1942 limited numbers arrived at the front as the Shoki (Demon Queller), but they were coolly received by pilots accustomed to pristine dogfighters. The Shoki did, in fact, display some dangerous characteristics, and extreme

maneuvers such as snap rolls and spins were forbidden. After a while, pilots came to appreciate the speed and ruggedness of the Shoki and developed a healthy respect for the plane. The same might be said for the Allies, who christened it the Tojo after Japan’s prime minister. Interestingly, this was the only Japanese warplane identified by a non-Western code name.

The Ki 44 saw limited deployment in China and was latter based at Palembang in Sumatra for defense of valuable oil installations there. As newer Allied fighters were encountered, subsequent versions of the Tojo introduced stronger engines and greater armament. It was not until 1944, when fleets of U. S. B-29s began plastering Japanese cities, that the Tojo came into its own. Climbing quickly, they proved one of few Japanese fighters capable of engaging the giant bombers at high altitude. The Ki 44 enjoyed some success in this mode, but by 1944 production was halted in favor of the all-around better Ki 84 Hayate. A total of 1,233 were built.

Type: Medium Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 67 feet; length, 54 feet, 1 inch; height, 13 feet, 11 inches

Weights: empty, 14,396 pounds; gross, 25,133 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 1,500-horsepower Nakajima Ha-109 radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 306 miles per hour; ceiling, 30,510 feet; range, 1,243 miles

Armament: 5 x 7.7mm machine guns; 1 x 20mm cannon; up to 2,205 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1942-1945

|

T |

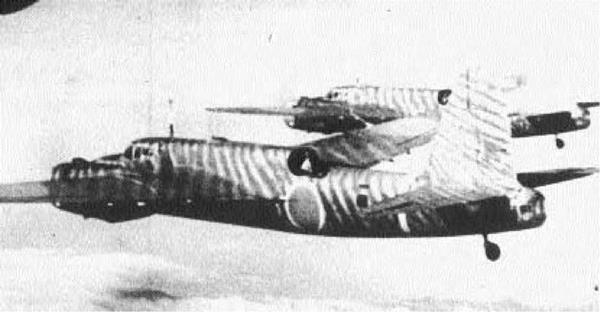

he Ki 49 was intended as a much-needed replacement for the aging Ki 21 Sally. However, it conferred few advantages in terms of performance, and most crews actually preferred the older machine.

Deployment of the Mitsubishi Ki 21 bomber had no sooner begun in 1938 than the Japanese army began contemplating its successor. That year the army staff drafted specifications for a new aircraft featuring crew armor, self-sealing tanks, and the first-ever tail turret mounted in an army bomber. Nakajima, which had earlier lost out to Mitsubishi and ended up producing Ki 21s under license, gained firsthand knowledge about their competitor’s product and sought to improve upon it. The prototype Ki 49 first flew in August 1939 as an all-metal, midwing aircraft with retractable undercarriage. Its inner wing possessed a wider chord than the outer sections to accommodate self-sealing fuel tanks. The trailing edge also mounted full-length Fowler flaps to enhance takeoff and climbing characteristics. The craft completed test flights, and pilots

praised its handling qualities but otherwise deemed it underpowered. Nonetheless, production was authorized in 1941, and the first Ki 49 units were deployed in China. Known officially as the Donryu (Storm Dragon), it performed well enough against weak Chinese resistance but represented only marginal improvement over the earlier Ki 21. It eventually received the Allied code name Helen.

The Ki 49 saw extensive service along the Japanese Empire’s southern fringes. It debuted during the February 1942 attack on Port Darwin, Australia, and was frequently encountered over New Guinea. But despite armor and heavy armament, the Helen proved vulnerable to fighters and lost heavily. Nakajima responded by fitting subsequent versions with bigger engines and more guns, but the type remained too underpowered to be effective. After the

U. S. invasion of the Philippines in 1944, where Ki 49s were sacrificed in droves, they were finally withdrawn from frontline service. Most spent the rest of their days as antisubmarine craft, transports, or kamikazes. Only 819 were built.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet, 10 inches; length, 32 feet, 6 inches; height, 11 feet, 1 inch Weights: empty, 5,864; gross, 8,576 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,900-horsepower Nakajima Ha-45 radial engine Performance: maximum speed, 392 miles per hour; ceiling, 34,450; range, 1,347 miles Armament: 2 x 12.7mm machine guns; 2 x 20mm cannons; up to 1,100 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1944-1945

|

T |

he Ki 84 was the best Japanese army fighter of World War II to reach large-scale production. Fast, well-armed, and well-protected, it could easily outfly the formidable P-51 Mustangs and P-47 Thunderbolts.

By 1942 the attrition of experienced Japanese pilots forced the High Command to reconsider its philosophy of fighter design. By default, they concluded that maneuverability had lost ground to high performance, firepower, and pilot survivability. Accordingly, specifications were issued for a new machine to replace the aging Ki 43s in service. Nakajima subsequently fielded the prototype Ki 84 that flew in April

1943. This was a handsome, low-wing fighter with an extremely advanced power plant, the Nakajima Ha-45 radial. To the surprise of many, the new design possessed impressive qualities of speed and climb without sacrificing the cherished maneuverability of earlier machines. More important, it was also well-armed for a Japanese fighter, mounting two cannons and two heavy machine guns. The decision was made to pur

sue production immediately, and the Ki 84 entered service as the Hayate (Gale) during the autumn of 1944. Allies gave it the code name Frank.

The first production batches of Ki 84s gave the 14th Air Force in China an extremely hard time, demonstrating marginal superiority over such stalwarts as the P-51 and P-47. As more became available, they fleshed out fighter units in the Philippines, where a major invasion was anticipated. In combat the Frank was an outstanding fighter plane, strong enough to be fitted with bombs for ground-attack purposes. However, its Achilles’ heel was the Ha-45 direct-injection engine, which was complex, required constant maintenance, and was frequently unreliable. Japan was also experiencing an alarming decline in quality control, for vital parts such as landing gear began inexplicably snapping off during touchdown. The Frank nonetheless gave a good account of itself until war’s end and confirmed Japan’s ability to design first-rate warplanes. Production of these outstanding craft came to 3,514 machines.