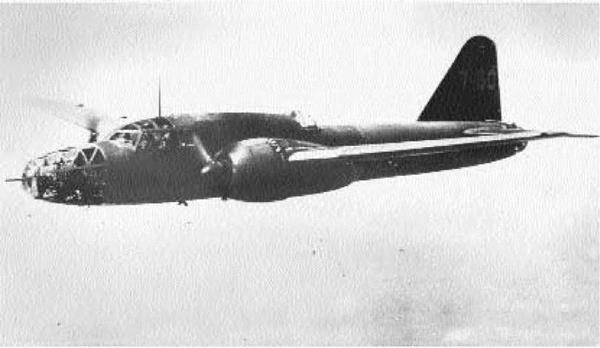

. LeO 451

Type: Medium Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 73 feet, 9 inches; length, 56 feet, 4 inches; height, 17 feet, 4 inches Weights: empty, 17,229 pounds; gross, 25,133 pounds Power plant: 2 x 1,140-horsepower Gnome-Rhone 14N 48/49 radial engines Performance: maximum speed, 308 miles per hour; ceiling, 29,350 feet; range, 1,429 miles Armament: 2 x 7.5mm machine guns; 1 x 20mm cannon; up to 3,307 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1939-1945

|

T |

he LeO 451 was the best French bomber of World War II and one of few available in quantity. It fought well during the Battle of France and also flew capably in the hands of Vichy French pilots.

No sooner had the Armee de l’Air become independent in April 1933 than it pressed for immediate expansion and modernization programs. Part of this entailed development of a new four-seat medium bomber capable of day and night operations. In 1937 the firm Liore et Olivier fielded its Model 451 prototype, which marked a breakthrough in French bomber design. It was an all-metal, midwing, twin-engine craft with a glazed nose and twin rudders. In contrast to the ungainly aircraft of the early 1930s, the LeO 451 was beautifully streamlined and performed as good as it looked. Operationally, however, the type suffered from technical detriments that were never fully corrected. It had been designed for 1,600- horsepower engines at a time when no such power plants were available. Hence, employing 1,000-horsepower motors, LeO 451s remained significantly un

derpowered and never fulfilled their design potential. Worse still, when the French government decided to acquire the bomber in quantity, bureaucratic lethargy militated against mass production. By September 1939 only five LeO 451s had been delivered.

The German onslaught in Poland energized French aircraft production, and when the Battle of France commenced in May 1940 around 450 LeO 451s were available. They had been designed for medium-level bombing, but the speed of the German blitzkrieg necessitated their employment in low-level ground attacks. The bomber served well in that capacity, but, exposed to enemy fighters and antiaircraft fire, serious losses ensued. Yet the type remained in production after France’s capitulation, with an additional 150 being acquired. These were actively flown against the Allies in North Africa before Vichy France was occupied by the Germans. They confiscated about 94 LeO 451s; stripped of armament, these were flown as transports. A handful survived into the postwar period as survey aircraft.

|

Czechoslovakia

Dimensions: wingspan, 44 feet, 11 inches; length, 33 feet, 11 inches; height, 11 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 3,704 pounds; gross, 5,820 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 635-horsepower Bristol Pegasus radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 174 miles per hour; ceiling, 23,620 feet; range, 435 miles Armament: 4 x 7.92mm machine guns; up to 1,102 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1933-1944

|

A |

useful craft, the Letov S 328 was designed for Finland yet deployed by Czechoslovakia. Ironically, it flew actively during World War II in the hands of numerous belligerents.

In 1931 the Czechoslovakian Letov firm, which had manufactured airplanes since 1918, developed a two-seat reconnaissance/utility machine for Estonia called the S 228. It was a fine machine, and the following year the Finnish government asked for a similar craft. A team headed by Alois Smolik responded with the S 328, which borrowed heavily from the earlier design. It was a single-bay biplane with staggered wings of equal length. Both the wings and fuselage were made of metal framework and fabric-covered, although the engine area sported alloy panels. Provisions were made for two forward-firing machine guns up front, with a similar armament for the gunner/ob – server. Like all Letov products, the S 328 was a first – rate machine, but orders from Finland never materialized. The changing political climate of Europe, occasioned by Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933,

then induced the Czech government to acquire S 328s in quantity. A total of 445 machines were constructed, including several night-fighter and floatplane variants.

In March 1939 German forces occupied Bo – hemia/Moravia and acquired all existing stocks of S 328. Interestingly enough, the type was kept in production for another year. The excellent Letovs were subsequently impressed into Luftwaffe service as trainers, but others were doled out to the puppet Slovakian air force. Several S 328s accompanied the invasion of Poland that year and acquitted themselves well. Two years later S 328s were present during the German invasion of the Soviet Union, although many Slovak pilots defected along with their aircraft. Those remaining in German hands were employed as night fighters to foil the harassing raids of Polikarpov Po 2s. Finally, a small number of S 328s ended up with the Bulgarian air force for patrolling the Black Sea. The hardworking Letovs saw their final service during the 1944 Slovakian uprising against German forces.

Type: Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 33 feet, 10 inches; length, 25 feet, 3 inches; height, 9 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 1,680 pounds; gross, 2,824 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 160-horsepower Mercedes D III liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 103 miles per hour; ceiling, 15,000 feet; range, 500 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns Service dates: 1916-1917

|

W |

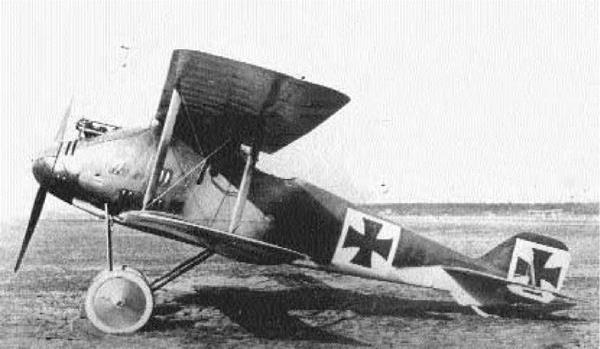

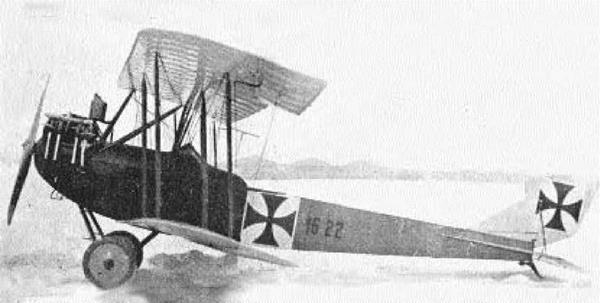

hen it appeared in 1916, the LFG Roland C II was an unusual and effective German reconnaissance craft of World War I. Simultaneously streamlined yet rotund, it was affectionately known to crew members as the “Whale.”

The firm Luftfahrzeug Gesellschaft was founded in 1906 with a view toward constructing airships. Shortly before the onset of World War I, it modified its name to LFG Roland to avoid confusion with another firm, LVG. For two years into the war, LFG manufactured Albatros fighters, but by 1916 the company was ready to field its own design.

The new craft debuted in the spring of 1916 as a two-seat reconnaissance vehicle of most unusual lines. In fact, compared to contemporary German observation craft, beset with numerous struts and wires, the LFG Roland C II represented a tremendous advance in the art of streamlining. The most obvious aspect of this was the plywood-covered monocoque fuselage, which was very deep and ta

pered off to the rear. The two wings were wedded directly to it, thereby closing the interplane gap and giving both pilot and gunner unrestricted views up and forward. The highly staggered wings were also buttressed by a single “I” strut to minimize drag. The net result was an extremely modern design that anticipated the CL-class aircraft of the late war. In light of its somewhat tubby appearance, the C II was unofficially dubbed the Walfisch (Whale).

In service the C II proved itself to be fast, rugged, and difficult to shoot down. On occasion, the nimble craft was called upon to serve as an escort fighter to slower C-series reconnaissance airplanes. However, its peculiarly thin wings gave it mediocre climbing abilities, and the pilot’s view downward was also poor, leading to a propensity for accidents while landing. Within a year the C II was withdrawn from service on the Western Front and relegated to secondary theaters and training functions. An estimated 250-300 had been constructed.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 29 feet, 4 inches; length, 22 feet, 8 inches; height, 10 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 1,397 pounds; gross, 1,749 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 180-horsepower Argus liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 112 miles per hour; ceiling, 16,400 feet; range, 230 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns

Service dates: 1917-1918

|

T |

he LFG Roland D II was a failed attempt to modify the successful C II Walfisch (Whale) into a single-seat fighter. Despite an attractive appearance, it was tricky to fly, heavy on the controls, and inferior to contemporary Albatros fighters.

By 1916 the outstanding performance of the two-seat LFG Roland CII induced that company to develop a single-seat fighter along similar lines. The prototype first flew in July of that year and bore unmistakable resemblance to its predecessor. Like the C II, the new D I possessed a rather deep, fishlike outline. The cross-sectioned oval fuselage was constructed from a wooden monocoque shell that left the engine almost completely buried. The front end possessed metal engine-access panels, typical Roland cooling vents, and terminated in a large, bowl-shaped propeller spinner. Meanwhile, the two equal-chord wings were unstaggered and lacked dihedral. Moreover, the upper span attached directly to the fuselage, completely filling in the gap. A relatively small wooden rudder and broad, trapezoidal tailplanes outfitted the

rear quarter. In view of the D I’s slimmer appearance, it was unofficially dubbed the Haifisch (Shark).

From the onset, unfortunately, the D I exhibited poor flying characteristics for a fighter. Both forward and downward views from the cockpit were obstructed by the wings, placing pilots at a serious disadvantage. In an attempt to rectify this deficiency, a new model, the D II, evolved with a modified center section for improved vision. This consisted of a long, narrow pylon and a cut-down cockpit. The aircraft, however, remained sluggish to maneuver, heavy on the controls, and clearly inferior to the Albatros scouts they were meant to replace. A total of 300 D IIs were manufactured, but in view of their inferior qualities they were confined mostly to secondary theaters like Macedonia and quiet sectors of the Western Front. A final version, the D III, emerged in late 1917 with more conventional struts affixing the upper wing, and 150 machines were eventually built, serving mostly as advanced trainers.

![]() Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Type: Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 45 feet, 11 inches; length, 29 feet, 6 inches; height, 11 feet, 1 inch

Weights: empty, 1,859 pounds; gross, 2,888 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 160-horsepower Daimler liquid-cooled engine

Performance: maximum speed, 85 miles per hour; ceiling, 9,843 feet; range, 180 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns

Service dates: 1914-1917

|

S |

leek-looking Lloyd biplanes were among the best of their kind in the early days of World War I. They performed useful field service before obsolescence relegated them to training duties.

The firm Ungarische Lloyd Flugzeug und Mo – torenfabrik AG fielded its first military biplane design in 1914, shortly before the commencement of World War I. Its C I was a streamlined design, unique in being entirely covered by wood, not fabric. It also possessed two-bay, swept-back wings whose trailing edges flared dramatically rearward. In 1914 a Model C I piloted by Henrik Bier set an altitude record of 20,243 feet, which brought it to the attention of the Austrian military. One day following the declaration of war against Serbia in August, Lloyd was immediately contracted to provide two – seat biplanes for reconnaissance purposes. The C I performed yeoman’s work over the Italian front for nearly two years and was the sole Austrian craft that could safely negotiate the 13,000-foot mountain ranges there. Within a year a new model, the C II,

had been introduced, which mounted a stronger engine and a single Schwarzlose machine gun for the observer. In 1916 the most numerous model, the C III, was deployed. It featured a 160-horsepower Daimler engine and a fixed machine gun on the upper wing that fired above the propeller arc. Despite these changes, the Lloyd remained a docile machine, stable in rough weather and possessing excellent gliding characteristics.

As the Allies introduced better fighter planes, the leisurely, underpowered Lloyds began suffering disproportionate losses. The company countered with the Model C IV, which adopted a two-bay system of wing supports to save weight. The final version, the C V, was more drastically revised with a shorter wingspan and a 220-horsepower Benz engine. It was faster than previous marks but also inherently less stable and therefore less popular. By war’s end, the remaining Lloyd aircraft still in service were retained for training purposes only. Nearly 500 of all versions had been acquired.

![]() Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Type: Reconnaissance; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 44 feet, 1 inch; length, 29 feet, 3 inches; height, 10 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 2,075 pounds; gross, 3,069 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 160-horsepower Daimler liquid-cooled engine

Performance: maximum speed, 85 miles per hour; ceiling, 11,483 feet; range, 250 miles Armament: 1 x 7.92mm machine gun; 485 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1914-1917

|

T |

he underpowered Lohner series was marginally obsolete throughout its service life. Nonetheless, these planes handled well in mountainous terrain and gave a good account of themselves.

In 1913 the firm Jakob Lohner Werke in Vienna constructed its first military land planes for the Austrian air service. The B I was a two-seat reconnaissance design built of wood, covered in fabric, and seated two crew members in a common cockpit. Its narrow fuselage, highly pointed cowling, and two – bay, swept-back wings gave it an exceptionally sleek appearance. As World War I progressed, the BII version was introduced in 1915 with minor refinements, followed by the B III a year later. This was the first Lohner to be armed, although it boasted but a single Schwarzlose machine gun for defense. A maximum of 485 pounds of bombs could also be carried aloft, which for the day was considered impressive.

In service the Lohners tended to be plodding, but they were rugged with excellent STOL (short takeoff and landing) characteristics. This made

them ideal for operating in mountain valleys along the Italian front, and they gradually replaced the aging Lloyd C Is and C IIs that preceded them. Lohn – ers frequently conducted air raids deep behind Italian lines, both singly and in formation, which could last five or six hours in duration. On February 14, 1916, the Austrians launched their most ambitious attack when 12 of the new 160-horsepower Daimler – powered Lohner B VII’s successfully struck Milan’s Porta Volta electrogeneration plant. This was accomplished by traversing 236 miles of dangerous mountain terrain and occasioned the loss of only two aircraft through mechanical failure. The Allies responded to such raids by deploying better air defenses, and the leisurely Lohners were eventually phased out by faster, more modern Hansa-Branden – burg C Is.

Lohner tried updating his basic design with the C I model, which featured reduced wing sweep and less bracing, but to no avail. By 1917 all surviving Lohners were consigned to training functions.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 42 feet, 7 inches; length, 24 feet, 5 inches; height, 9 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 2,046 pounds; gross, 3,058 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 200-horsepower Benz BZ IV liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 106 miles per hour; ceiling, 19, 680 feet; range, 350 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns

Service dates: 1917-1918

|

L |

ate model LVG C aircraft were the most numerous of their class and among the largest. They shared many design features of the contemporary DFW C V, having originated with the same engineer.

The firm Luft-Verkehrs Gesellschaft had produced numerous C-series aircraft for the German military since 1915, mostly designed by the Swiss engineer Franz Schneider. These were functional, solidly constructed craft and well-adapted for artillery-spotting and reconnaissance. In November 1916 an LVG C II became the first aircraft ever to drop bombs on London. As the war continued, it became apparent that more modern machines were necessary to keep apace of the latest Allied fighters. In 1917 it fell upon a new engineer, Sabersky-Mus – sigbrod, formerly of DFW, to initiate a new series of C-type airplanes.

In the autumn of 1917, LVG unveiled its new C V model, which boasted considerable improvements over earlier versions. It was a large airplane,

spanning 42 feet, but also neatly designed and compact for its size. In this respect, it also bore marked resemblance to the DFW C V, an earlier product of Sabersky-Mussigbrod. The new C V maintained the company’s reputation for fine-looking, rugged airplanes, and it served with distinction along the Western Front. However, in service the exposed engine, radiator, and numerous struts seriously impeded the pilot’s forward view.

To correct deficiencies associated with the C V, LVG developed a new model, the C VI, in 1918. At first glance the two machines appeared similar, but the C VI placed greater emphasis on practicality than aesthetics. The fancy spinner was eliminated in favor of a plain propeller hub, the wings acquired a slight positive stagger to afford the pilot a better view, and the entire craft was lightened to improve performance. The C VI was completely successful in the field, and more than 1,100 were constructed. They served alongside the C V versions up through the end of the war.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 39 feet; length, 26 feet, 6 inches; height, 9 feet, 4 inches Weights: empty, 1,587 pounds; gross, 2,183 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 160-horsepower Isotta-Fraschini water-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 117 miles per hour; ceiling, 20,340 feet; range, 300 miles Armament: 2 x 7.7mm machine guns Service dates: 1918-1923

|

T |

he elegant Macchi M 5 was Italy’s most numerous flying-boat fighter of World War I. Developed from a captured Austrian machine, they rendered excellent service in a variety of capacities.

Prior to World War I, the Societa Anonima Nieuport-Macchi firm of Varese was preoccupied with manufacturing fine coaches. It obtained licenses to build various Nieuport aircraft in 1912, an activity that expanded during the war years. The firm’s expertise was limited to land planes until May 1915, when Italian forces captured an Austrian Lohner LI flying-boat fighter intact. The government authorized Macchi to build copies of the craft for its own use as the L 1. In 1916 a more refined version, the M 3, was introduced, featuring more powerful engines and aerodynamic streamlining. Macchi constructed 200 of these fine aircraft.

By 1917 the Austrians were employing Hansa – Brandenburg KDW flying-boat fighters with better performance than the M 3s, so Macchi undertook improving their design. The prototype M 5 was con

structed in the spring of 1918. Like its forebear, it was a handsome airplane with obvious Nieuport influence. The two wings were of uneven length, with the top being longer in both length and chord, and both were secured in place by two sets of the famous Nieuport-type vee struts. A powerful Isotta – Fraschini motor was affixed to the bottom of the top wing, under which sat the pilot. From there he operated a pair of machine guns buried in the airplane’s nose.

The Macchi M 5 was attractive, and it flew as good as it looked. The craft possessed high speed comparable to most land-based fighters and was fully acrobatic with a good rate of climb. M 5s were deployed throughout the spring of 1918 and saw active service against Austrian naval forces throughout the Adriatic. It was also flown by a small number of U. S. Navy pilots sent to Italy as observers. By 1918 the Macchi floatplane fighters vied with their bigger Caproni cousins as the most famous Italian aircraft of World War I.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan. 34 feet, 8 inches; length, 26 feet, 10 inches; height, 11 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 4,451 pounds; gross, 5,710 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 870-horsepower Fiat A.74 RC.38 radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 312 miles per hour; ceiling, 29,200 feet; range, 540 miles Armament: 2 x 12.7mm machine guns Service dates: 1939-1945

|

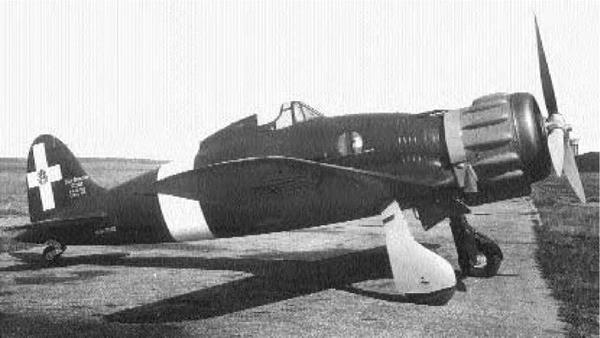

D |

elightful to fly, the Saetta (Lightning Bolt) was the most numerous Italian fighter of World War II. It suffered from the usual Italian attributes of being underpowered and underarmed yet gave a good account of itself.

The biggest handicap facing the Italian aviation industry in the 1930s was the lack of high-powered inline engines. Thus, when the transition was made to all-metal monoplane fighters in 1935, these craft were inevitably equipped with bulky, high-drag radials. In 1936 Dr. Mario Castoldi, famed designer of the Macchi Schneider Cup racing planes, conceived what was then an excellent design around the 840-horsepower Fiat A.74 engine. It was an all-metal, low-wing machine with a fully enclosed cockpit, stressed skin, and two heavy machine guns for armament. A unique feature was the wings’ trailing edge, which was completely hinged and interconnected with the ailerons. Test flights demonstrated that the new MC 202 possessed viceless characteristics, being highly maneuverable and responsive to controls. As good as it was, the Saetta was still slower and possessed less fire

power than contemporary British Hurricanes and Spitfires as well as German Bf 109s. Nonetheless, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini wanted modern-looking aircraft to replace the popular biplanes fighters still in use, so in 1938 the MC 200 entered production. After the first models were viewed suspiciously by conservative-minded Italian fighter pilots, an open cockpit was reinstalled.

When Italy entered World War II in June 1940, only 156 Saettas were on hand. They witnessed their baptism of fire over Malta, suffering considerably at the hands of modern British fighters. Italian losses overall proved so disturbing that Germany’s X Fliegerkorps (air division) was moved down in support. The MC 200s were subsequently encountered in greater numbers throughout North Africa. Italians pilots did commendable work despite great odds but were finally outclassed as better opposition materialized. Curiously, several Saettas operated against the Red Air Force in Russia until 1943, claiming 88 kills at a loss of only 15. Only a handful survived at war’s end. A total of 1,153 were built.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 34 feet, 8 inches; length, 29 feet; height, 9 feet, 11 inches Weights: empty, 5,545 pounds; gross, 6,766 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,175-horsepower Daimler-Benz DB 601A liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 372 miles per hour; ceiling, 37,730 feet; range, 475 miles Armament: 2 x 7.7mm machine guns; 2 x 12.7mm machine guns Service dates: 1941-1945

|

T |

he sleek Folgore (Thunderbolt) was Italy’s best all-around fighter of World War II. Fast and maneuverable, it arrived in too few numbers to alter the balance of power.

One of few advantages of an Italian alliance with Nazi Germany was access to advanced aviation engine technology. Once the superb Daimler-Benz DB 601A in-line engine was imported by Macchi, Dr. Mario Castoldi was convinced that the potential of his MC 200 design could finally be realized. He then melded the German engine to existing airframes to create the MC 202 Folgore, one of the best Italian fighters of World War II. The new fighter employed the basic outline of the earlier craft and almost the exact tooling, so production was greatly facilitated. In 1940 test flights revealed that the streamlined Folgore enjoyed a 60-mile-per-hour advantage over the earlier Saetta, with commensurate improvements in climb rate. Neither were any of the sweet flying characteristics adversely affected. It even enjoyed the advantage of an additional pair of wing-mounted

machine guns. The MC 202 was deployed in strength throughout 1941, and it demonstrated superiority to both the Hawker Hurricane and the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk in the Western Desert. Had the craft been deployed in numbers a year earlier, Axis control of the air might have been established. Nonetheless, the Folgore distinguished itself along a number of fronts, including Russia, where it completely mastered the numerous MiGs and LaGGs opposing it. A total of 1,200 were built.

In 1943 Macchi unveiled its last and best fighter of the war, the MC 205 Veltro (Greyhound). This came about by marrying the MC 202 airframe to an even more powerful DB 605A engine. The resulting fighter easily matched North American P-51 Mustangs and late-model Spitfires. It was also more heavily armed than its ancestor, sporting a pair of 20mm cannons. After the 1943 Italian surrender, the Germans seized several examples and outfitted a Luftwaffe Gruppe that flew continuously until war’s end. Only 289 Veltros were manufactured.

Type: Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 38 feet; length, 27 feet; height, 9 feet, 8 inches Weights: empty, 1,793 pounds; gross, 2,458 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 160-horsepower Beardmore liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 104 miles per hour; ceiling, 16,000 feet; range, 400 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns; 260 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1916-1917

|

T |

he aptly named Elephant was too large to serve as an effective escort fighter. Instead, it functioned better as a hard-hitting low-level bomber.

In the summer of 1915, Martinsyde engineer A. A. Fletcher conceived plans for a new and very modern escort fighter. The design was large by necessity, as it was required to hold sufficient fuel to complete missions lasting up to four hours. The resulting prototype then flew as a two-bay biplane fighter with staggered, broad-chord wings. It was of conventional wood-and-fabric construction, and the fuselage was fitted with a close-fitting metal cowling. A single Lewis machine gun sat on the top wing above the pilot, owing to the lack of interrupter gear, while a second gun was strangely situated behind him, firing backward, to ward off attacks from that quarter. Test results were encouraging, so the craft entered production as the Martinsyde G 100. In view of its large size for a fighter, pilots quickly dubbed it the Elephant.

The first G 100s reached France in the spring of 1916, and they were initially deployed in penny packets of two or three aircraft per reconnaissance squadron. The big plane flew well and possessed good range, but its sheer size precluded the agility necessary to combat nimble German fighters. However, in view of its excellent range and lift, Elephants quickly found work as light bombers with No. 27 Squadron, the only unit so equipped. In service the G 100s were strong and could handle great amounts of damage. Their payload was also considerable, and No. 27 Squadron conducted numerous effective raids on German positions. Several Elephants were also deployed to Palestine and Mesopotamia for bombing and strafing duties against the Turks. Production of G 100s reached 100, and they were followed by 171 slightly more powerful G 102s. The big craft were retired from service in mid-1917, although several carried on as trainers. Their memory is perpetuated by today’s No. 27 Squadron, whose unit heraldry displays an elephant.

|

Dimensions: rotorspan, 32 feet, 4 inches; length, 38 feet, 11 inches; height, 9 feet, 10 inches

Weights: empty, 2,820 pounds; gross, 5,290 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 429-horsepower Allison 250-C20B turboshaft engines

Performance: maximum speed, 150 miles per hour; ceiling, 17,000 feet; range, 388 miles

Armament: none, or 6 x HOT antitank missiles

Service dates: 1976-

|

T |

he rotund BO 105 is Germany’s first postwar helicopter and helped pioneer new rigid-rotor technology. It is renowned for high performance and agility at low altitude, especially as an antitank platform.

Design of the BO 105 was initiated in 1962 by Messerschmitt-Bolkow-Blohm (MBB) in response to a German government specification for new helicopters to replace the Alouette IIs in service. These would be the first such machines to originate in Germany since World War II. The prototype emerged in 1967 as a standard-looking pod-and – boom affair, but the BO 105 was designed from the onset to employ the radically different rigid-rotor technology. In most helicopters, the rotors are relatively loose so blade angle can be pitched downward during forward flight. This system allows for rapid climbing but is unable to sustain much in the way of negative-G forces—that is, rapid sinking. The new rigid rotor, as the name implies, was hingeless and kept the blades at right angles to the main rotor at all times. It was a very strong arrangement

and capable of resisting high negative-G forces. A helicopter thus equipped could rise quickly over obstacles in the conventional sense—and then sink past them with equal rapidity. Moreover, the BO 105 was fully acrobatic and maneuverable. Its military potential was immense, and the German army enthusiastically ordered 312 machines for the Herres – flieger (army aviation).

In service the BO 105 received two designations. The first, VBH, is a dedicated reconnais – sance/liaison craft for close work with field units. The PAH 1, meanwhile, is especially rigged as an antitank platform. It mounts up to six HOT wire – guided antitank missiles and carries a variety of sighting and imaging technology. Both versions are also equipped for nighttime operations and, by dint of their great maneuverability, can easily utilize terrain for cover at low altitude. A total of 1,200 BO 105s have been built and exported to 18 countries worldwide. With constant upgrades, they will remain potent weapons well into the twenty-first century.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 32 feet, 6 inches; length, 29 feet; height, 8 feet, 2 inches Weights: empty, 5,893 pounds; gross, 7,491 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,475-horsepower Daimler-Benz BD 605 liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 386 miles per hour; ceiling, 37,890 feet; range, 350 miles Armament: 1 x 20mm cannon; 2 x 13mm machine guns Service dates: 1937-1945

|

T |

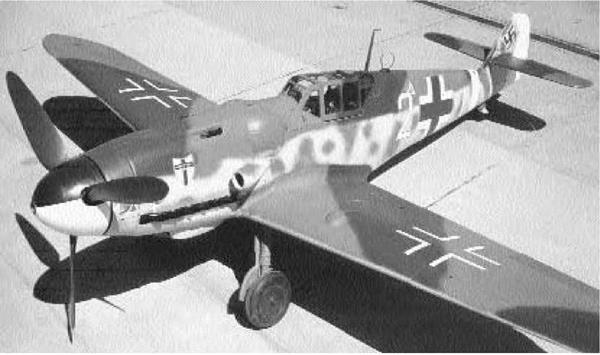

he Bf 109 was one of history’s greatest combat aircraft and the most widely produced German fighter of World War II. Small and angular, its very lines seemed to exude menace.

Willy Messerschmitt began developing his benchmark fighter in 1933 once the Luftwaffe desired to substitute its Arado Ar 68 and Heinkel He 51 biplanes. The prototype flew in 1935 as a rather angular, low-wing monoplane with a fully enclosed cockpit and narrow-track landing gear. Results were impressive, and in 1937 the new Bf 109B fighter outpaced all other rivals at the International Flying Meet in Zurich, Switzerland. By 1939 the first production model, the Bf 109E, was introduced, featuring a bigger engine and heavier armament. As a fighter, the diminutive craft flew fast and maneuvered well, features that helped secure German air superiority at the start of World War II. Simply put, Bf 109s annihilated all their outdated opposition until encountering Supermarine Spitfires during the 1940 Battle of Britain. Although speedier than its British opponent, Bf 109Es turned somewhat slower and never achieved superiority.

As the war ground on, successive new models were introduced to keep the five-year-old design solvent. The F model was aerodynamically refined, with rounder wings and tail surfaces, as well as a bigger engine. It was the best-handling variant, but in 1942 the most numerous version, the Bf 109G, made its appearance. It featured a stronger engine and heavier armament but sacrificed the sweet handling characteristics of earlier versions. Worse yet, German war planners failed to provide for new designs, so the Bf 109G remained in production long after its growth potential ceased. Late-model H and K versions tried interjecting better high-altitude performance into the old workhorse with some success, but they never became available in quantity. Nonetheless, leading German ace Eric Hartmann scored all 451 victories in his beloved Messer – schmitt. By war’s end, no less than 33,000 Bf 109s had been produced. Moreover, Spain continued constructing them up until 1956, and they also served in the postwar air forces of Israel and Czechoslovakia.

Type: Fighter; Night Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 53 feet, 3 inches; length, 39 feet, 7 inches; height, 13 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 12,346 pounds; gross, 15,873 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 1,110-horsepower Daimler-Benz liquid-cooled, in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 352 miles per hour; ceiling, 35,760 feet; range, 745 miles Armament: 5 x 7.92mm machine guns; 2 x 20mm cannons; up to 2,205 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1939-1945

|

T |

he fearsome-looking Bf 110 was actually rather defenseless in the face of determined fighter opposition. However, it found its niche as a nocturnal predator and accounted for 60 percent of Germany’s night-fighter defenses.

The notion of long-range strategic fighters arose simultaneously in several countries during the 1930s. In Germany, as elsewhere, they were envisioned as escorts for heavy bomber forces then under development. In 1936 Willy Messerschmitt fielded his second warplane design, the twin-engine Bf 110, for the task. It was an advanced, all-metal design with twin rudders and a long greenhouse canopy. Test flights showed that the airplane was extremely fast, but it handled sluggishly. Moreover, the death of General Walter Wever in 1936 led to the cancellation of Germany’s heavy bomber program, hence the new craft was without a mission. The Bf 110 was nonetheless ordered into production as a heavy fighter and deployed in strength just prior to World War II. The Luftwaffe held high expectations for it.

In the early days of the war, the Bf 110s easily swept aside obsolete Polish and French machines, fully living up to its role as a Zerstorer (Destroyer). Thus, in the summer of 1940 they were confidently thrown into the Battle of Britain, but they took staggering losses at the hands of nimble Spitfires and Hurricanes. The Bf 110s were so outclassed that they required escorts of single-engine Bf 109 fighters! Thereafter, Bf 110s were deployed in secondary theaters as ground-attack craft. Production of the aging craft began to wane when, in 1943, the failure of the Me 210 caused production to be accelerated. This time the Bf 110 was outfitted as a night fighter and equipped with heavy cannons and radar systems. Fast and stable, it made an ideal platform for nocturnal warfare and destroyed several hundred British bombers. In sum, the Bf 110 exhibited many fine qualities, but it was simply not on par with modern singleengine fighters. By war’s end, more than 6,000 machines had been constructed.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 30 feet, 7 inches; length, 19 feet, 2 inches; height, 9 feet, 1 inch

Weights: empty, 4,206 pounds; gross, 9,502 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 3,750-pound thrust Walter liquid-fuel rocket motor

Performance: maximum speed, 593 miles per hour; ceiling, 39,500 feet; range, 50 miles

Armament: 2 x 30mm cannon

Service dates: 1944-1945

|

T |

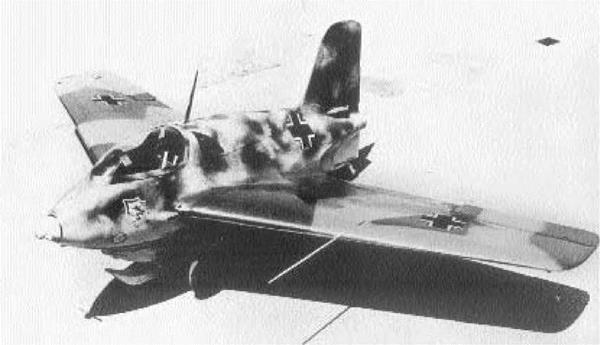

he revolutionary Komet was the world’s first rocket-propelled fighter and the fastest aircraft of World War II. Fast and lethal-looking, it often posed greater hazards to its own pilots than the enemy.

The Me 163 had its origins in the work of Dr. Alexander Lippisch, the world’s leading exponent of tailless gliders. He joined the Messerschmitt company in 1939 and, despite personal antipathy for Willy Messerschmitt, set about developing a rocket – powered glider. The prototype emerged in 1941 as a rather small, but very futuristic, swept-wing design. Built of metal and wood, the new craft dispensed with landing gear to save weight. Accordingly, it lifted off on a jettisonable dolly and landed on a retractable skid. But when rocket motors finally became available, even greater technical problems arose. The Komet was powered by a combination of two highly combustible fuels, C-Stoff (hydrazine hydrate and methyl alcohol) and T-Stoff (hydrogen peroxide and water). The two ignited when combined, providing tremendous thrust for about eight minutes. However, the practice of fueling the Me 163

was unpredictable, and the slightest misstep led to catastrophic explosions. Test flights were nonetheless successful, reaching unprecedented speeds of nearly 600 miles per hour. In 1944 the Me 163 entered production as a last-ditch weapon against the seemingly unstoppable Allied bomber streams. Around 350 were built.

In service the aptly named Komet (from the large flame it exuded) had a short but spectacular career. It skyrocketed to altitudes of 30,000 feet in only two minutes and traversed bomber formations so fast that gunners could scarcely draw a bead. However, closing speeds were tremendous and allowed for few bursts. Consequently, in nine months of combat, only 15 or so bombers were claimed by Komets. Moreover, many Me 163s were lost, mostly upon landing, when residual fuel left in the tanks exploded without warning. For all its shortcomings, the Me 163 possessed excellent performance for its day and reflects considerable German ingenuity. Had time existed for additional research, the Komet might have evolved into a formidable weapon.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 40 feet, 11 inches; length, 34 feet, 9 inches; height, 12 feet, 7 inches

Weights: empty, 8,378 pounds; gross, 14,110 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 1,984-pound thrust Junkers Jumo 004B turbojet engines

Performance: maximum speed, 540 miles per hour; ceiling, 37,565 feet; range, 652 miles

Armament: 4 x 30mm cannon

Service dates: 1944-1945

|

W |

ith its unmistakable sharklike lines, the Me 262 was the world’s first operational jet fighter. It might have reestablished German aerial supremacy had sufficient jet engines been available.

In 1938 the German Air Ministry approached Willy Messerschmitt to create a radically different fighter craft, one powered by new turbojet engines then under development. The first prototype emerged in April 1941 but had to be flown with a conventional nose-mounted engine. The Me 262 was a low-wing, all-metal monoplane of stressed-skin construction. The wings were swept, and the first prototypes landed on tailwheels, but subsequent versions employed tricycle landing gear. However, the Luftwaffe displayed little interest initially, and the project received few construction priorities. It was not until July 1942 that the first jet-powered flight could be held, but the new craft was a marvel to behold. It was at least 100 miles per hour faster than the best Allied piston-powered fighters, and it handled extremely well. At this time the Third Reich

was being battered by enormous fleets of Allied heavy bombers, so it became imperative to deploy the Me 262 as an air-superiority weapon. However, when Adolf Hitler witnessed a test flight, he ordered that the craft be outfitted as a high-speed bomber! This did little to facilitate production, and efforts were further beset by a lack of engines.

The first Me 262s deployed in August 1944, less than a year before the war in Europe ended. There were ongoing problems with engine reliability and fuel shortages, but the vaunted Schwalbe (Swallow), as it was dubbed, created havoc with Allied bombers. On March 18, 1945, a force of 37 Me 262s attacked U. S. B-17s near Berlin, scything down 15 with a loss of two jets. The bomber version, known as the Sturmvogel (Storm Petrel), had also debuted, but it was tactically misused. Although 1,430 Me 262s were built, only a handful actually saw combat. They claimed 150 Allied aircraft—and may have shot down many more—save for Hitler’s meddling and the Luftwaffe’s initial indifference.

Type: Glider; Transport

Dimensions: wingspan, 180 feet, 5 inches; length, 93 feet, 6 inches; height, 31 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 64,066 pounds; gross, 99,210 pounds

Power plant: 6 x 1,140-horsepower Gnome-Rhone 14N radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 149 miles per hour; ceiling, 14,760 feet; range, 808 miles

Armament: 2 x 20mm cannons; 2 x 13mm machine guns

Service dates: 1942-1945

|

T |

he lumbering Gigants were among the biggest aircraft used in World War II. They carried useful payloads but were highly vulnerable when confronted by Allied fighters.

The Me 321 evolved in October 1940 when the German invasion of Great Britain seemed imminent. The German Air Ministry requested development of giant glider craft to ferry troops and equipment across the English Channel by air. Willy Messer – schmitt, who had designed gliders since childhood, readily complied, and within two weeks he conceived the Me 321 Gigant (Giant). This was a high – wing, braced monoplane featuring mixed construction. Both wing and fuselage were made from steel tubing, strengthened by wood, and then covered in fabric. The Gigant was also the first airplane to possess clamshell nose doors for ease of loading. Up to 22 tons of men and supplies could be hauled aloft and safely landed, making it the biggest transport of World War II. The prototype debuted in the spring of 1941 and, although somewhat fatiguing for a single

pilot to handle, flew well. Getting airborne was tricky, however, and usually meant being towed by three Bf 110s, or a single He 111Z (two bombers lashed together at midwing). The Me 321 entered production that year, and 211 were built. Most served along the Eastern Front ferrying supplies.

At length it was decided that a powered model, the Me 323, would be safer and offer more strategic flexibility. Accordingly, an Me 321 was fitted with six French Gnome-Rhone radial engines and fuel tanks. The added weight almost reduced the payload by half, and the giant craft still needed to be towed or employ rockets to assist takeoff. Nonetheless, the Me 323 entered production in 1943 and saw widespread service in Russia, North Africa, and the Mediterranean. The slow-moving transports proved easy prey for Allied fighters, and on one occasion British Spitfires annihilated 14 of 16 Gigants at sea. Given the hazards of interception, the lumbering behemoths were restricted to rear-area supply missions.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 53 feet, 7 inches; length, 40 feet, 11 inches; height, 14 feet Weights: empty, 16,574 pounds; gross, 21,276 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 1,850-horsepower Daimler-Benz 603A liquid-cooled in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 364 miles per hour; ceiling, 32,180 feet; range, 1,050 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns; 4 x 20mm cannons; up to 2,205 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1943-1945

|

T |

he formidable-looking Me 410 was an outgrowth of the earlier Me 210, an embarrassing failure. It was fast and capable but never fulfilled design expectations.

In 1937 the German Air Ministry began looking for a successor to the Bf 110 Zerstorer (Destroyer), the Luftwaffe’s only strategic fighter. Willy Messer – schmitt originated his second warplane design, the Me 210, which was heavily based upon the initial machine. Like its precursor, the new craft had twin engines and twin rudders, but it also sported tapered wings and lengthened engine nacelles. The effect was a handsome machine that proved very unstable in flight and prone to stalls and spins. Subsequent modifications introduced a single rudder, but Marshal Hermann Goring, the Luftwaffe chief, ordered

1,0 machines produced before the design was perfected. Consequently, when the Me 210 became operational in 1941, it still possessed all the old vices of the prototype. Several crashed due to bad handling, and the government canceled its contract after 300

machines. Several officials also demanded Messer – schmitt’s resignation from the company bureau.

In an attempt to save both the Me 210 and his own reputation, Messerschmitt tried revamping the balky craft. The resulting Me 410 appeared almost indistinguishable from its predecessor, but it had a lengthened fuselage and nacelles, along with automatic wing slots on the leading edges. Larger engines were also fitted, and the Me 410, when it appeared in 1943, was a significant improvement. Through most of 1944, the Hornisse (Hornet) was employed as a night bomber over England, where its high speed made interception difficult. It was also utilized to defend the Reich, where its heavy armament caused havoc with bomber formations. However, like all two – engine fighters, the Me 410 was at a severe disadvantage when opposing single-engine craft and suffered heavy losses. By the time production ceased in the fall of 1944, no less than 1,160 had been produced. Their contribution to the war effort proved negligible and constituted a waste of valuable resources.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 33 feet, 9 inches; length, 26 feet, 9 inches; height, 8 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 5,996 pounds; gross, 7,694 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,350-horsepower Mikulin liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 398 miles per hour, ceiling, 39,370 feet; range, 777 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.62mm machine guns; 1 x 12.7mm machine gun; up to 440 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1941-1943

|

T |

he MiG 3 was an impressive high-altitude interceptor when it appeared in 1941 and won its designers the coveted Stalin Prize. However, it proved woefully inadequate at lower levels and could not compete with better German fighters.

In 1939 Artem Mikoyan and Mikhail Gurevich, veterans of the Polikarpov design bureau, proposed a high-altitude interceptor, the MiG 1. This was a highly streamlined, modern-looking craft with a long cowling, retractable landing gear, and an open cockpit. Constructed from steel tubing and covered with wood, the prototype flew in April 1940 with impressive speed and performance at high altitude. However, the extreme length of the nose—designed to accommodate the biggest possible engine around the smallest possible fuselage—rendered it inherently unstable. In fact, the MiG 1 displayed downright vicious handling characteristics, but the Soviet government needed fighters quickly, and so the design entered production. In 1941 the MiG bureau attempted to rectify earlier shortcomings with a new machine, the MiG 3. This was essentially a cleaned-

up version of the earlier craft, with a fully enclosed canopy, a cut-down rear deck for better vision, and increased dihedral on the outer wing sections. The new design performed only marginally better, but the government awarded Mikoyan and Gurevich the prestigious Stalin Prize.

The onset of the German invasion of June 1941 only underscored the inadequacy of the MiG 3 as a fighter. Unstable and unforgiving, it was tiring to fly and could not engage nimble Messerschmitt Bf 109s at low altitudes, where the majority of battles were fought. It was also unsatisfactory as an interceptor, being too lightly armed with machine guns to inflict much harm upon bombers. Nonetheless, the Soviets, hard-pressed for aircraft of any kind, dutifully employed the MiG 3 in frontline service for nearly three years. Russian pilots accepted the assignment stoically—and suffered commensurately. By 1943 most MiG 3s had been withdrawn from combat functions and were restricted to high-speed reconnaissance missions. Total production exceeded 4,000 units.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 33 feet, 1 inch; length, 35 feet, 7 inches; height, 11 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 7,500 pounds; gross, 12,750 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 5,950-pound thrust Klimov VK-1 turbojet engine

Performance: maximum speed, 668 miles per hour; ceiling, 51,000 feet; range, 665 miles

Armament: 2 x 23mm cannons and 1 x 37mm cannon; up to 1,100 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1950-

|

T |

his classic design was the most successful of early Soviet jet fighters and a complete shock to the West. Its debut during the Korean War put the world on notice that Russian aircraft were among the best in the world.

At the end of World War II, the Soviets inherited a trove of advanced German technology, especially concerning jet aviation. Stalin, fearful of trailing the West in its use, demanded the creation of new jet-powered aircraft for the Red Air Force. In 1946 engineers Artem Mikoyan and Mikhail Gurevich conceived what was then a highly advanced fighter design. It was a midsize, fairly compact machine with swept midmounted wings and high tail surfaces. The MiG 15 also carried a bomber-killing three-cannon pack that lowered down on wires for ease of servicing. Up until then, Soviet attempts with jet aircraft largely failed on account of using weak German Jumo engines of insufficient thrust. However, Great Britain’s shortsighted Labor government had fatefully arranged the export of several Rolls-Royce

Nene jet engines, then the world’s best. This proved a technological windfall of the first order, and the engine was quickly copied by Soviet engines as the VK – 1. Once installed in the MiG 15 prototype, the result was a world-class jet fighter that was faster and could outclimb and outturn almost any jet employed by the West. The MiG 15 entered mass production in 1949 and received the NATO designation FAGOT.

MiG 15s were an unwelcome surprise to UN forces when these fearsome new machines suddenly appeared over North Korea in November 1950. Only rapid deployment of equally advanced North American F-86 Sabres kept control of the skies from communist hands. These two adversaries were almost evenly matched, and in 1953 a defecting North Korean pilot, Ro Kim Suk, gave the West its first intact example. MiG 15s continued in production throughout the 1950s until an estimated 18,000 were made. They were employed by all Soviet allies and client states, with many two-seat trainer versions still in use.

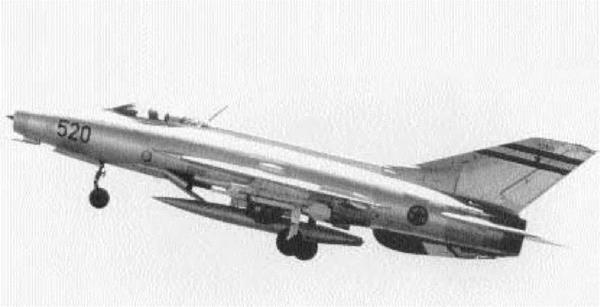

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 23 feet, 6 inches; length, 51 feet, 9 inches; height, 13 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 12,051 pounds; gross, 21,605 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 15,653-pound thrust Tumansky R-25-300 turbojet engine

Performance: maximum speed, 1,385 miles per hour; ceiling, 62,336 feet; range, 600 miles

Armament: 1 x 23mm cannon; up to 4,409 pounds of bombs or rockets

Service dates: 1959-

|

T |

he classic MiG 21 is the most extensively exported jet fighter in history. It has fought in several wars and continues in frontline service four decades after its appearance.

The experience of air combat in Korea forced the Mikoyan design bureau to draw up radical plans for a new air-superiority fighter. This machine would have to be lightweight, be relatively simple to build, and possess speed in excess of Mach 2. The prime design prerequisite entailed deletion of all unnecessary equipment not related to performance. No less than 30 test models were built and flown through the mid – to late 1950s before a tailed-delta configuration was settled upon. The first MiG 21s were deployed in 1959 and proved immediately popular with Red Air Force pilots. They were the first Russian aircraft to routinely operate at Mach 2 and were highly maneuverable. Moreover, the delta configuration enabled the craft to remain controllable up to high angles of attack and low air speed. One possible draw

back, as with all deltas, was that high turn rates yielded a steep drag rise, so the MiG 21 lost energy and speed while maneuvering. This was considered a fair trade-off in terms of overall excellent performance. More than 11,000 MiG 21s were built in 14 distinct versions that spanned three generations of design. They are the most numerous fighters exported abroad, and no less than 50 air forces employ them worldwide. The NATO code name is FISHBED.

The MiG 21 debuted during the Vietnam War (1964-1974), during which they proved formidable opponents for bigger U. S. fighters like the McDon – nell-Douglas F-4 Phantom. Successive modifications have since endowed them with greater range and formidable ground-attack capability, but at the expense of their previously spry performance. Russian production of the MiG 21 has ended, yet China and India build, refurbish, and deploy them in great numbers. These formidable machines will undoubtedly remain in service for many years to come.

Type: Fighter; Ground Attack

Dimensions: wingspan, up to 45 feet, 8 inches; length, 54 feet, 9 inches; height, 15 feet, 9 inches Weights: empty, 22,487 pounds; gross, 39,242 pounds Power plant: 1 x 18,849-pound thrust Soyuz turbojet engine

Performance: maximum speed, 1,553 miles per hour; ceiling, 60,695 feet; range, 715 miles Armament: 1 x 23mm Gatling gun; up to 8,818 pounds of bombs or rockets Service dates: 1970-

|

T |

he MiG 23 was the first Soviet combat plane equipped with variable-wing geometry. Its success led to an equally capable ground-attack version, the MiG 27.

By the mid-1960s the Red Air Force wanted to supplement its vaunted MiG 21s with air-superiority fighters that could also perform ground-attack work. The new machine would have to approximate the formidable performance of such Western stalwarts as the F-4 Phantom and F-105 Thunderchief. Furthermore, excellent STOL (short takeoff and landing) ability from unfinished fields was also required. The Mikoyan design bureau initially toyed with revised delta configurations before settling upon a “swing-wing” version like the General Dynamics F-

111. The new MiG 23 prototype first flew in 1967 as a high-wing jet with an extremely sharp profile. The wing could be deployed at three different angles for takeoff, cruise, and fighting mode and, when fully extended, would assist in achieving shorter landing distances. To ensure high performance at high

speed, the craft also carried adjustable “splitters” at the front of each air intake. The first MiG 23s had no sooner been deployed in 1970 than it was determined to optimize them for air supremacy and forego ground-attack functions for a subsequent model.

The impracticality of endowing the MiG 23 with good tactical strike abilities led to development of a related design, the MiG 27. This was essentially a stripped-down MiG 23 refitted with a distinct flattened nose housing a laser range finder. The craft lost its intake splitters, as excessively high speed is considered unnecessary at low altitude. The afterburner was also simplified and lightened to compensate for weight lost at the front end. Not surprisingly, Russian pilots dubbed the MiG 27 Utkonos (Duck-nose) on account of its odd appearance. More than 3,000 of both versions have been built, and collectively they are identified by the NATO designation FLOGGER. Neither craft is considered a match for their Western equivalents.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 46 feet; length, 78 feet, 2 inches; height, 20 feet

Weights: empty, 44,092 pounds; gross, 79,807 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 27,000-pound thrust Tumansky R-31 turbojet engines

Performance: maximum speed, 1,849 miles per hour; ceiling, 80,000 feet; range, 901 miles

Armament: 9,636 pounds of missiles

Service dates: 1973-

|

A |

n ingenious design, the elusive MiG 25 was once the doyen of Soviet high-altitude reconnaissance. It continues on today as a formidable cruise-missile interceptor.

Toward the end of the 1950s the United States embarked upon developing a viable Mach 3 high-altitude bomber, the North American XB-70 Valkyrie. Such a craft would fly so high and fast that it appeared virtually immune to Soviet missiles and conventional jet aircraft. Aware of its weakness, the Red Air Force scrambled for a new, ultra-high speed interceptor to thwart such a menace. Mach 3 operations posed daunting operational difficulties, but the Mikoyan design bureau tackled them with characteristic aplomb. The first MiG 25 prototype flew in 1964 with complete success. This was a large, if squat, machine of futuristic appearance. Highly streamlined, it possessed a high-mounted, swept wing, an extremely pointed profile, and twin rudders that canted outward. It was powered by two huge Tumansky engines and mounted equally imposing airducts on either side of the fuselage. Because heat

arising from air friction at Mach 3 was intense, the MiG 25 was constructed mostly of expensive stainless steel and titanium—anything less would melt! Every design priority reflected an unyielding emphasis on speed and high-altitude performance, but outside of this regimen the MiG 25 maneuvered like a brick. It nonetheless became operational as a fighter and reconnaissance craft in 1973—a decade after the XB-70 program was canceled. The NATO code name is FOXBAT.

During the 1970s the MiG 25 performed considerable overflight activity in the Middle East and could not be intercepted by the redoubtable Israeli air force. The West got its first up-close look when MiG 25 pilot Viktor Belenko defected to Japan in September 1976. Engineers marveled at the ingenuity of design yet crudity of construction. Since then, FOX – BATs have undergone considerable electronic and engine upgrades, making them even more formidable. Modern versions are equipped with the very latest look down/shoot down radar capable of detecting and destroying U. S. cruise missiles at any altitude.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 37 feet, 3 inches; length, 56 feet, 9 inches; height, 15 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 24,030 pounds; gross, 40,785 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 11,111-pound thrust Klimov/Leningrad RD-33 turbofan engines Performance: maximum speed, 1,519 miles per hour; ceiling, 55,575 feet; range, 932 miles Armament: 1 x 30mm cannon; up to 6,614 pounds of bombs and rockets Service dates: 1984-

|

T |

he MiG 29 is one of the most modern and capable fighter planes ever designed. It confirms Russia’s ability to construct weapons of lethality equal to Western counterparts.

In 1972 the Soviet government issued demanding specifications for a new lightweight fighter with secondary ground-attack capability to offset the aging MiG 21s, MiG 23s, and Su 17s in service. In addition, such a machine would have to be capable of engaging and defeating the formidable Grumman F-14s and McDonnell-Douglas F-15s of the United States, as well as the forthcoming General Dynamics F-16 and McDonnell-Douglas F-18. As usual, the Mikoyan design bureau undertook the assignment with determination and originality. By 1977 it had arrived at a solution: the modest-sized MiG 29. This was an ultrasleek and futuristic-looking machine with a beautifully blended high-lift, low-drag wing and fuselage. The twin engines were widely spaced and outwardly canted; twin rudders were also provided. One of the most unusual features was the underwing air intakes.

Like all Russian warplanes, MiG 29s are expected to operate off of rough, unprepared airstrips. To minimize any chance that dirt or rocks might be ingested by an engine, they are covered by panel doors that open automatically when lifting off and close again upon touchdown. While these are shut, air is fed continuously to the engine through louvers near the wing roots. In terms of maneuverability, the MiG 29 is a sterling dogfighter, light on the controls and highly responsive. An estimated 1,350 have been built and deployed by Russia and former Soviet client states. The NATO designation is FULCRUM.

As expected, the MiG 29 was a popular addition to the Red Air Force stable, placing Russian pilots on equal footing with potential Western adversaries. A look down/shoot down fire-control system, helmet – actuated sights, and accurate missiles make it possibly the world’s best interceptor. Its handling is even more impressive considering that all controls are hydraulic and devoid of fly-by-wire technology. The FULCRUM remains every fighter pilot’s dream.

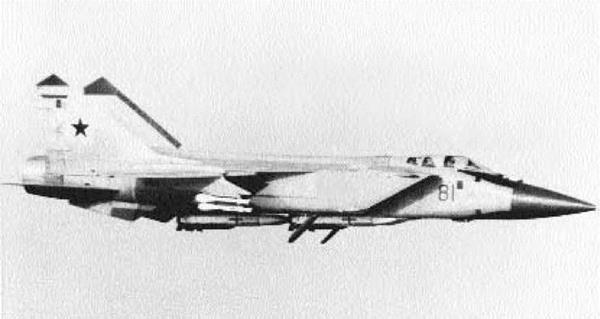

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 44 feet, 2 inches; length, 74 feet, 5 inches; height, 20 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 48,115 pounds; gross, 101,859 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 34,170-pound thrust Aviavidgatel D-30F6 turbofan engines

Performance: maximum speed, 1,865 miles per hour; ceiling, 67,600 feet; range, 745 miles

Armament: 1 x 30mm cannon; up to six homing missiles

Service dates: 1982-

|

T |

he MiG 31 is a heavily armed long-range interceptor designed to engage and destroy fast, low- flying targets. Linked by computer, four of these fearsome machines can effectively blanket 590 miles of airspace!

By the late 1980s Russia anticipated that the threat of strategic bombardment from the United States had undergone fundamental changes. Instead of subsonic, low-flying B-52s, Russia now faced the prospect of ultrasophisticated and stealthy B-1 Lancers backed my myriads of terrain-following cruise missiles. In 1975 the Mikoyan design bureau was tasked with creating a totally new machine to counter this new threat. After several studies, it elected to begin with a revamped version of the MiG 25 FOXBAT, a high-speed, high-altitude interceptor. Despite its international celebrity as an unstoppable spy plane, the FOXBAT was incapable of supersonic speed at low altitudes. Thus, the solution posed was to build a new craft: the MiG 31. It shared some common ancestry with the earlier machine but was, in fact, a much more capable interceptor. Like the

MiG 25, the MiG 31 (NATO code name, FOXHOUND) is a big, squat airplane with twin engines and twin tails. However, it differs by seating two crew members in tandem, possessing larger air intakes for low-altitude work, as well as extended afterburner nozzles. Moreover, its construction has dispensed with heavy stainless steel in favor of lighter titanium and nickel steel. All told, the MiG 31 displays lower absolute top speed than the MiG 25 but enjoys much better handling and maneuverability. Its role is to assist the faster Sukhoi Su 27s by plugging gaps in Russia’s defensive radar net.

The biggest changes in the MiG 31 are electronic. It boasts state-of-the-art Zaslon phased – array nose radar, which can detect targets as far out as 125 miles. In addition, the computerized fire – control system can track up to 10 targets independently and engage four. The MiG 31 is also capable of linking to other aircraft via computer and their fire being coordinated by a team leader. To date a total of 280 FOXHOUNDS have been manufactured and deployed.

|

Dimensions: rotorspan, 69 feet, 10 inches; length, 59 feet, 7 inches; height, 18 feet, 6 inches Weights: empty, 14,990 pounds; gross, 26,455 pounds Power plant: 2 x Klimov TV3-117MT turboshaft engines

Performance: maximum speed, 155 miles per hour; ceiling, 14,760 feet; range, 289 miles Armament: 2 x rocket or gunpods Service dates: 1962-

|

F |

or four decades, the Mi 17 has been among the most numerous large helicopters in the world. It was the workhorse of the former Soviet Union and continues in active service with many nations.

Toward the end of the 1950s, the Mil design bureau attempted to update and enlarge its existing Mi 4 helicopters with a view toward greater power and lifting capacity. By 1961 it had developed the Mi 8, which retained the transmission and tailboom of the earlier craft but relocated the engine overhead and the canopy forward. The new craft was much bigger internally but somewhat underpowered, so a second engine was added. When the Mi 8 became operational in 1962, it was among the world’s foremost military helicopters. It could lift up to 28 fully armed troops and carry them to their objective with good reliability. As Soviet imperialism spread through client states in the 1970s, more often than not the Mi 8s were there. Cuban and East German advisers employed them to good effect in Ethiopia, Angola, and

Nigeria. However, the Mi 8s enjoyed far less success when they were outfitted as gunships and deployed in huge numbers during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Muslim guerillas, equipped with CIA – supplied Stinger missiles, took a heavy toll on the lumbering giants. The craft still operates under the NATO designation HIP.

In 1981 the Mil bureau decided to update its basic design by introducing the Mi 17. This was a standard Mi 8 refitted with the more powerful engines and transmission from the naval Mi 14; the tail – rotor was relocated to the port side. The craft also employs a unique system for maintaining engine synchronization. Should one engine lose power or fail completely, the other automatically reaches a contingency rating of 2,200 horsepower to ensure steady flight. The Mi 8/17 family is a rugged, dependable series of military machines with a long service life ahead. An estimated 13,000 have been built and are operated by 60, predominately Third World, nations.

Type: Attack Helicopter

Dimensions: rotorspan, 56 feet, 9 inches; length, 57 feet, 5 inches; height, 13 feet, 1 inch

Weights: empty, 18,078 pounds; gross, 26,455 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 2,190-horsepower Klimov TV3-117 turboshaft engines

Performance: maximum speed, 208 miles per hour; ceiling, 14,750 feet; range, 456 miles

Armament: 1 x 23mm Gatling gun; 4 x gun or rocket pods

Service dates: 1973-

|

D |

escribed as a “flying tank,” the formidable Mi 24 is the world’s biggest and most heavily armed helicopter gunship. It offers heavy firepower, good speed, and troop-carrying capacity in one lethal package.

The year 1967 witnessed introduction of the Bell AH-1 Cobra, the world’s first dedicated helicopter gunship. It proved highly effective against unprotected infantry during the Vietnam War and added new dimensions of firepower into battlefield equations. Soviet planners watched such developments closely and decided they needed to counter this latest Western threat. It fell upon Mikhail Mil to design Russia’s first gunship, drawing upon his earlier experiences with large machines like the Mi 8 transport helicopter. He utilized the engine and transmission of the earlier craft, melded to a somewhat smaller, heavily armored fuselage. This contained high proportions of steel and titanium, making it nearly imperious to small-arms fire. To this were fitted large anhedral winglets that produced added lift and acted as convenient platforms for carrying weapons.

A squad of eight fully armed soldiers could also be transported. Finally, the crew of two sat in a squared-off cabin with large glazed windows. The overall effect was impressive, and when the first Mi 24s were sighted in East Germany, NATO dubbed them HINDs.

Greater operational experience with the Mi 24 resulted in a total redesign of the forward portion. Henceforth, newer models sported two staggered canopies that granted better vision, along with a four – barrel machine gun in a chin turret. Tactically speaking, the HIND D was now more involved with battlefield firepower than in transporting troops. These behemoth gunships were employed in great numbers throughout the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, sometimes with great success against lightly armed guerillas. It was not until the United States supplied Stinger antiaircraft missiles that the big helicopters sustained meaningful losses. Mil 24s are still regarded as formidable antitank platforms in more conventional modes of warfare. An estimated 2,300 have been built and are still flown by 20 nations.

Type: Transport

Dimensions: rotorspan, 105 feet; length, 110 feet, 8 inches; height, 26 feet, 9 inches

Weights: empty, 62,170 pounds; gross, 123,450 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 10,000-horsepower ZMKB D-136 turboshaft engines

Performance: maximum speed, 183 miles per hour; ceiling, 15,090 feet; range, 497 miles

Armament: none

Service dates: 1983-

|

B |

y many measures, the giant Mi 26 is the world’s most powerful helicopter. It has an internal storage capacity equivalent to the Lockheed C-130 Hercules!

By the early 1970s the Soviet government desired a heavy-lift replacement for its already impressive Mi 6 helicopters. The new machine was intended to possess twice the power and lifting ability of the older craft. These features were necessary for transporting great amounts of supplies to undeveloped regions of the country, like Siberia, to assist development there. The Mil design bureau under N. M. Tishchyenko settled for a slightly smaller version of the existing craft, one absolutely crammed with power and aeronautical efficiency. In 1977 the first Mil 26 took flight and went on to establish several world payload and altitude records. At first glance it was outwardly similar to the Mi 6 but was driven by the world’s first eight-blade rotor. This device allowed the helicopter to absorb power from the massive, twin ZMKB engines, and it made for

smooth, almost vibration-free flight. It also allowed the Mi 26 to dispense with the two pronounced winglets of the earlier craft. For loading purposes, the Mi 26 boasts an integral rear loading ramp and two powered clamshell cargo doors. It can carry up to 44,000 pounds of cargo or 100 fully equipped troops on a very strong titanium floor. It flies in both civilian and military guises with the NATO code name HALO.

Considerable ingenuity was expended in weight-saving measures. In fact, the Mi 26 is actually

2,200 pounds lighter that the less-capable Mi 6. Part of this comes from the rotor assembly, which is titanium; the huge rotor blades are made from steel spars and fiberglass. The big craft can be flown in any weather conditions using state-of-the-art navigation and computerized flight assistance. On autohover it can reputedly remain motionless only 5 feet off the ground! This triumph of aeronautical engineering is destined to be the world’s chopper-lift champ for some time. A total of 70 have been built.

Type: Trainer

Dimensions: wingspan, 39 feet; length, 35 feet, 7 inches; height, 9 feet, 3 inches

Weights: empty, 4,293 pounds; gross, 5,573 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 870-horsepower Bristol Mercury XX radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 242 mile per hour; ceiling, 25,100 feet; range, 393 miles

Armament: 1 x.303-inch machine gun

Service dates: 1939-1950

|

T |

he Master was the most numerous advanced British trainer of World War II. In its original form it possessed performance almost rivaling the fabled Hurricanes and Spitfires.

By 1935 the advent of high-performance monoplanes necessitated adoption of training craft with similar flight characteristics. In 1937 M. G. Miles fielded his Kestrel design, a low-wing monoplane made of wood frames and covered in plywood. A crew of two was housed in a tandem cockpit, and the instructor’s seat could be raised in flight for better view on takeoffs and landings. Powered by a 745-horsepower Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine, it reached 300 miles per hour, slightly slower than Hurricanes and Spitfires employing much more powerful engines. However, the Air Ministry remained disinterested, and the project subsided. The following year it reversed that decision, and Miles was required to modify the fuselage and reposition the radiator from the nose to the wing’s center section. Moreover, a derated Kestrel XXX engine was

utilized, which slowed the new craft down by 70 miles per hour. The Master, as it was christened, was still delightful to fly and handled very much like a fighter. In June 1938 the ministry adopted it under Specification 16/38 and ordered 500 copies. This was the largest order placed for a training plane to that date.

The first Master Is were not deployed at flight schools until the fall of 1939. Thereafter, they trained thousands of British pilots in the art of fighter tactics. As the war progressed, a shortage of Kestrel engines developed, so the Master II arose by mounting an 870-horsepower Bristol Mercury radial engine. This spoiled the airplane’s fine lines but resulted in a 16-mile-per-hour increase in speed. When these stocks ran out, the Master III was fitted with a lower-rated 825-horsepower Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior and suffered a commensurate decrease in top speed. By war’s end, a total of 3,227 of the wonderfully agile Masters had been delivered. Many were retained as trainers until 1950.

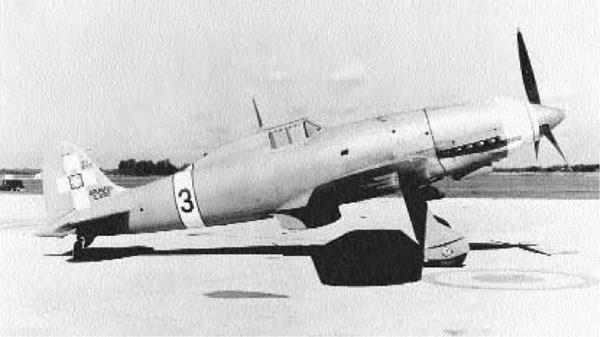

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet, 1 inch; length, 24 feet, 9 inches; height, 10 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 2,681 pounds; gross, 3,759 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 710-horsepower Nakajima Kotobuki radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 273 miles per hour; ceiling, 32,150 feet; range, 746 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.7mm machine guns

Service dates: 1937-1945

|

T |

he diminutive A5M set aviation standards as the world’s first all-metal, carrier-based monoplane. Commencing in 1937 it helped secure Japanese control of the air during the war against China.

In 1934 the Imperial Japanese Navy issued new specifications for a monoplane fighter that could top 217 miles per hour in level flight and reach 6,000 feet in less than six minutes. It devolved upon a Mitsubishi design team under Jiro Horikoshi to devise an appropriate solution. He responded with a prototype that, at the time it appeared, was revolutionary for Japan’s fledgling naval air arm. The new craft was an all-metal, low-wing monoplane with fixed, spatted wheels. It was totally covered in stressed metal and flush-riveted to reduce drag. During test flights in 1936 the prototype reached 280 miles per hour, 60 miles per hour faster than the specifications, but problems were encountered with the wing shape. It originally possessed a gull-shaped plan – form, but this subsequently gave way to a graceful, elliptical design. Once fitted to a more powerful engine, the new craft exhibited better speed and per

formance than contemporary Japanese biplanes, so in 1937 it entered the service as the A5M. It debuted as the world’s most advanced carrier-based fighter, and during World War II Allied intelligence gave it the code name Claude.

No sooner were A5Ms built than they deployed from Japanese carriers operating off the Chinese coast. These demonstrated their mettle over Nanking in September 1937 by shooting down 10 Chinese-piloted Polikarpov I 16 monoplanes without loss. Thereafter, the Claudes facilitated Japanese control of the air over Chinese coastal regions. A fully enclosed cockpit was fitted to the second model in an attempt to improve the A5M, but the swashbuckling Japanese pilots objected, and later models reverted back to an open cockpit. In the early days of the Pacific war, Claudes were the most numerically important Japanese fighter, but they were rapidly outclassed by newer Allied fighters. Most were retired by the summer of 1942 to serve as trainers, but after 1945 many became kamikazes. Total production ran to 1,094 machines.

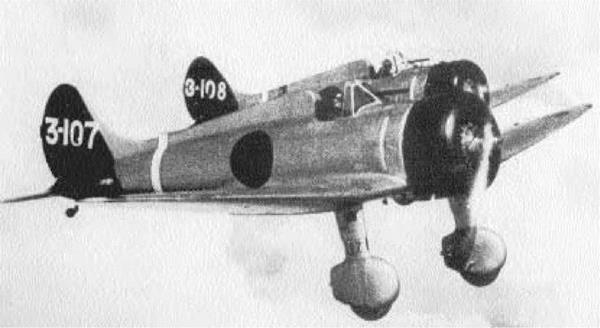

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet, 1 inch; length, 29 feet, 11 inches; height, 11 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 4,136 pounds; gross, 6,508 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,130-horsepower Nakajima NK1F radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 351 miles per hour; ceiling, 36,255 feet; range, 1,193 miles Armament: 2 x 7.7mm machine guns; 2 x 20mm cannon Service dates: 1940-1945

|

T |

he legendary A6M (the dreaded Zero) was the first carrier-based fighter in history to outperform land-based equivalents, and it arrived in greater quantities than any other Japanese aircraft. Despite the Zero’s aura of invincibility, better Allied machines gradually rendered it obsolete.

As early as 1937 the Imperial Japanese Navy began searching for a craft to replace its A5M carrier – based fighters. That year it issued specifications so stringent that only Mitsubishi was willing to hazard a design. Specifically, the navy wanted a fighter of prodigious range and maneuverability, one able to defeat bigger land-based opponents. A design team headed by Jiro Horikoshi originated a prototype in 1939. The A6M was a study in aerodynamic cleanliness despite its bulky radial engine. It had widetrack undercarriage for easy landing and was heavily armed with two cannons and two machine guns. Tests proved it possessed phenomenal climbing and turning ability, so it entered production in 1940, the Japanese year 5700. Henceforth, the new fighter was known officially as the Type 0, but it passed into history as the Reisen, or Zero.

A small production batch of 30 Zeroes was sent to China in the summer of 1940 for evaluation, and they literally swept the sky of Chinese opposition. Such prowess was duly noted by Claire L. Chennault, future commander of the famed Flying Tigers, but his warnings were ignored. Zeroes subsequently spearheaded the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, and over the next six months they ran roughshod over all Allied opposition. However, following the Japanese defeat at Midway in June 1942, the fabled fighter lost much of its ascendancy to new Allied fighters and a growing shortage of experienced pilots. New and more powerful versions of the Zero were introduced to stem the tide, but relatively weak construction could not withstand mounting Allied firepower. Furthermore, the additional weight of new weapons and equipment eroded its famous powers of maneuver. By 1945 most A6Ms had been converted into kamikazes in a futile attempt to halt the Allied surge toward the homeland. A total of 10,964 were constructed.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 82 feet; length, 53 feet, 11 inches; height, 12 feet, 1 inch

Weights: empty, 11,552 pounds; gross, 17,637 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 1,300-horsepower Mitsubishi Kinsei radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 258 miles per hour; ceiling, 33,725 feet; range, 3,871 miles

Armament: 4 x 7.7mm machine guns; 1 x 20mm cannon; 1,764 pounds of bombs or torpedoes

Service dates: 1937-1945

|

A |

t the time of its appearance, the Nell was one of the world’s most advanced long-range bombers. It participated in many famous actions in World War II before assuming transport duties.