. Hansa-Brandenburg D I

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 27 feet, 10 inches; length, 21 feet, 10 inches; height, 9 feet, two inches

Weights: empty, 1,482 pounds; gross, 2,073 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 150-horsepower Daimler liquid-cooled engine

Performance: maximum speed, 111 miles per hour; ceiling, 16,404 feet; range, 260 miles Armament: 1 x 7.92mm machine gun Service dates: 1916-1917

|

T |

he infamous “Star-strutter” was one arguably of the worst fighter planes ever designed. Its slow climb, poor forward vision, and unpredictable stalls earned it an ignominious nickname: “The Flying Coffin.”

By 1916 the Austrian Luftfahrtruppe (Austrian air service) was in urgent need for new fighter craft to counter more modern French and Italian designs. It fell upon Ernst Heinkel of the German firm Hansa und Brandenberg Flugzeugwerke to provide a prototype, as the company’s owner was an Austrian national. Initially christened the KD Spinne (Spider), Heinkel’s new craft was both bizarre and ugly. It was outwardly a standard biplane configuration, its squarish wings sporting a positive stagger, with a relatively small rudder buried deep in the fuselage. What made the craft unique was the arrangement of the bracing struts, namely, four sets of vees converging between the two wings in a star arrangement. This innovation enabled the KD to dispense with the usual wire rigging but did little to enhance its performance. Tests flights further revealed that the

plane, dubbed “Star-strutter” by the press, was slow and unstable. More important, the placement of the radiator directly over the engine nearly obstructed the pilot’s frontal view. Yet the pressing need for new fighters left Austria little recourse but to allow Heinkel’s abomination to enter production. In the spring of 1916 these unsightly machines were deployed to field units as the D I.

Predictably, pilots immediately disliked the Star-strutter on account of its strange appearance and poor handling. Although relatively fast for its day, the D I possessed vicious stall characteristics, and several were lost to crashes. Moreover, its single machine gun, housed in a conspicuous fairing above the top wing, was inaccessible to the pilot and further denigrated its marginal handling. At length, the D I acquired the nickname Die Fliegender Sarg (The Flying Coffin). The Ufag and Phonix companies tried improving the craft with modified tail configurations, with little success. The hated D Is remained in frontline service until their welcome replacement by Aviatik D Is in mid-1917.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 44 feet, 3 inches; length, 30 feet, 3 inches; height, 9 feet, 10 inches

Weights: empty, 2,205 pounds; gross, 3,296 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 150-horsepower Benz Bz III liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 109 miles per hour; ceiling, 16,405 feet; range, 400 miles

Armament: 3 x 7.92mm machine guns

Service dates: 1918-1926

|

T |

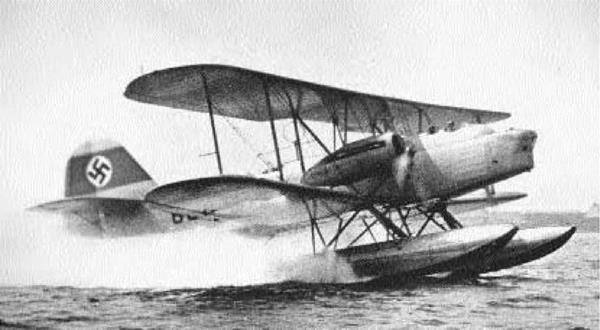

he fast, maneuverable W 29 was one of World War I’s best floatplane fighters. From numerous stations along the Northern European coast, it continually menaced British shipping and aircraft with great effect.

In the early days of World War I, German naval installations along the North Sea shore were constantly raided by numerous well-armed British flying boats. The lack of an effective naval fighter prompted Hansa-Brandenburg’s talented engineer, Ernst Heinkel, to develop a series of floatplane fighters to counter them. The first, the W 12 of 1917, was a uniquely shaped biplane fitted with pontoons, and it rendered effective service. By the spring of 1918, however, Heinkel realized that biplane fighters encumbered by floatation gear were unequal to the task of fending off the latest Allied seaplanes. The only solution was to develop a monoplane fighter with less drag and more performance.

The new Hansa-Brandenburg machine was designated the W 29 and among the finest deployed during the war. It was essentially a modified W 12

fitted with an enlarged, low-mounted wing whose surface area nearly equaled that of the biplane. Like all aircraft of this series, the W 29’s fuselage formed a knife-edge rearward and canted upward. A rather small rudder was placed on the very end and partially drooped down under the fuselage. It was powered by a 150-horsepower Benz BZ III engine, which gave it excellent speed, and the overall design displayed great agility. The W 29 subsequently entered into production, and a total of 75 were completed.

In service the W 29 proved itself the terror of the North Sea. The detachment commanded by Oberleutnant Friedrich Christiensen routinely engaged and shot up numerous Felixstowe F2A flying boats. His W 29s were also responsible for sinking three British patrol boats in a single action, and Christiensen himself seriously damaged a British submarine. After the war, these superlative floatplanes were utilized by Denmark and Finland until 1926. Its basic features were also incorporated into similar designs throughout the postwar period.

Type: Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 30 feet; length, 26 feet, 9 inches; height, 10 feet, 2 inches Weights: empty, 2,734 pounds; gross, 3,609 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 640-horsepower Rolls-Royce Kestrel VI water-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 223 miles per hour; ceiling, 29,500 feet; range, 270 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine guns Service dates: 1931-1939

|

T |

he Hawker Fury was the first British warplane to exceed 200 miles per hour in level flight. It united the virtues of beautiful design, high performance, and great maneuverability into one formidable machine.

Sydney Camm began working on the Hawker Fury in 1927 with an initial design called the Hornet. The Air Ministry at that time had been calling for fighters with superior speed and climbing capabilities, even at the expense of range. Camm took it upon himself to disregard ministry specifications favoring radial engines and fitted a new Rolls-Royce Kestrel in-line engine to the old Hornet body. The result was a masterpiece of aeronautical engineering: the Fury I. It was an unequal-span, single-bay biplane with wings supported by “N” struts splaying outward. The fuselage was oval in cross-section and covered in fabric save for a sharply pointed engine area, enclosed by metal. The result was a sleek-look – ing craft of particularly pleasing lines. Test flights demonstrated it was 30 miles per hour faster than the Bristol Bulldog and climbed faster as well. The

ministry was so impressed that it rewrote new specifications around this craft! In 1931 the first Fury Is were deployed; 146 were built. Pilots immediately took a liking to this aerodynamic doyen, which was both fast and nimble.

In 1936 the Fury II appeared, sporting a larger engine and more fuel capacity. This version climbed 30 percent faster than the original model but at the cost of shortened range. Pilots also reported that it was inferior at high altitudes to the Gloster Gauntlet. Nevertheless, the Royal Air Force acquired an additional 118 machines. The airplane’s sparkling performance naturally attracted foreign governments, and about 50 were exported to Norway, Persia, Portugal, Yugoslavia, and South Africa. Three even clandestinely found their way to Spain during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1938). One was captured by Nationalist forces, and another was rebuilt by Republicans from wreckage of the original two, so the Fury ended up fighting for both sides! By 1939 these elegant biplanes had been supplanted by another Camm masterpiece: the Hawker Hurricane.

Type: Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 37 feet, 3 inches; length, 29 feet, 4 inches; height, 10 feet, 5 inches Weights: empty, 2,530 pounds; gross, 4,554 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 525-horsepower Rolls-Royce Kestrel IB liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 184 miles per hour; ceiling, 21,230 feet; range, 470 miles Armament: 2 x.303-inch machine gun; up to 500 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1930-1938

|

T |

he successful Hart spawned more variants than any other British design of the 1930s. It became one of the most advanced and significant bomber aircraft of the interwar period.

The adaptable Hawker Hart evolved in response to Air Ministry Specification 12/26, which mandated creation of a day bomber with unprecedented speed. Hawker’s Sydney Camm originated plans for such a craft in 1927, and when developed as a prototype it exerted profound military implications. The new craft was a standard single-bay biplane with unequal, staggered wings made of metal frame and covered in fabric. They were supported by “N”-type interplane struts that splayed outward. The fuselage was oval-sectioned, metal-framed, and canvas-covered. The most prominent characteristic of the Hart was its extremely pointed cowl and spinner, giving it a decidedly streamlined appearance. This was in complete contrast to the blunter, radial – engine machines of the day. The Hart flew well and extremely fast, so fast that it embarrassed all British

fighters then in production—none could catch it! The ministry was suitably impressed by Camm’s brainchild, so in 1930 the Hawker Hart entered the service as a light bomber.

The overall excellence of Camm’s creation can be gauged by the sheer number of variants spawned by his original design. The Fleet Air Arm went on to acquire the Hawker Osprey, a navalized version, in quantity. They were followed in short order by the Hawker Audax, built as an army cooperation type; the Hardy, a general-purpose type; and the Hector, another army cooperation craft. The Hart series also inspired its replacement, the Hawker Hind, which was just as striking and even more capable. The total number of Harts numbered roughly 1,000, exclusive of subtypes, making it one of the most numerous light bombers of the 1930s. They lingered in frontline service before being supplanted by Bristol Blenheims in 1938. Although best remembered as a light bomber, the Hart is more significant for having stimulated development of even faster British fighters.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 33 feet, 8 inches; length, 45 feet, 10 inches; height, 13 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 14,400 pounds; gross, 24,600 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 10,150-pound thrust Rolls-Royce Avon turbojet engine

Performance: maximum speed, 620 miles per hour; ceiling, 50,000 feet; range, 443 miles

Armament: 4 x 30mm cannons; up to 6,000 pounds of bombs or rockets

Service dates: 1954-

|

O |

stensibly the most beautiful jet fighter ever built, the rakish Hunter is also Britain’s most successful postwar aircraft. At the half-century mark of its lifespan, several machines are still in active service.

By 1948 the British Air Ministry was looking for an updated aircraft to replace its Gloster Meteors and issued Specification F.4/48 for Britain’s first swept-wing fighter. Sir Sydney Camm of Hawker, who had helped sire the Hurricane, Tempest, and Sea Fury, quickly promulgated a design of classic proportions and performance. The P 1967 made its first test flight in 1951 with great success. This was a midwing, stressed skin monoplane with wings of 40- degree sweep and a relatively high tail. The new craft exhibited sparkling performance in the transonic range and entered the service in 1954—much to the delight of Royal Air Force pilots. Hunters possessed world-class performance, were highly maneuverable, and proved very much the equal of any fighter then in production. However, an early prob

lem encountered was engine failure after firing the four 30mm cannons positioned near the nose. The problem was traced to the ingestion of gun fumes, which induced a flameout, but this was corrected in subsequent versions. The most numerous of these was the FGA Mk 9, a dedicated ground-attack aircraft that could deliver a sizable load of bombs and rockets. By 1964 a total of 1,985 Hunters had been constructed.

The Hunter also proved itself one of the most outstanding export successes of the century. India, Iraq, Switzerland, Belgium, Sweden, and Jordan, among others, all imported the sleek fighter and employed it for years after its departure from the RAF stable. The various Indo-Pakistani wars of the 1970s proved that the aging fighter had lost none of its punch, and it was also flown against the redoubtable Israeli air force with good effect. The Swiss were so enamored of their beloved Hunters that they made no real attempt to replace them until 1991! A handful are still performing frontline service in Zimbabwe.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 40 feet; length, 32 feet; height, 13 feet, 1 inch Weights: empty, 5,800 pounds; gross, 8,100 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 1,280-horsepower Rolls-Royce Merlin XX liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 336 miles per hour; ceiling, 35,600 feet; range, 460 miles Armament: 8 x.303-inch machine guns; up to 1,000 pounds of bombs or rockets Service dates: 1938-1945

|

F |

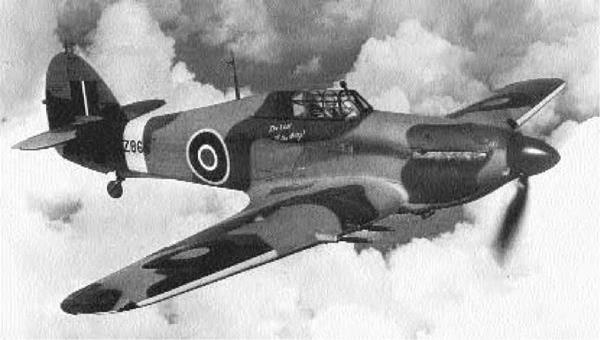

ew aircraft were as significant to England’s survival as the famous Hurricane. During the Battle of Britain it shot down more aircraft than the vaunted Spitfire, and later rendered distinguished service in the Mediterranean and Pacific theaters.

Upon receipt of Air Ministry Specification F.7/30 in 1930, Sydney Camm decided to leapfrog existing biplane technologies by designing a monoplane fighter. He did this by incorporating lessons learned from the excellent but aging Hawker Fury biplanes then extant. The prototype Hurricane first flew in November 1935 to great applause. From a construction standpoint, it employed arcane features such as metal tubing structure and fabric covering, but this rendered the craft strong and easily repaired. The Hurricane was also very streamlined for its day, possessed retractable landing gear, and carried no less than eight machine guns, the first British fighter so armed. The design exuded great promise, so in 1934 the Air Ministry issued Specification F.36/34, even before flight-testing concluded, to obtain them as quickly as possible. The urgency was

well justified, and by the advent of World War II, in 1939, Hurricanes constituted 60 percent of RAF Fighter Command’s strength.

The 1940 Battle of France proved that Hurricanes were marginally outclassed by Bf 109Es, so throughout the ensuing Battle of Britain they were usually pitted against bombers.

Their great stability and heavy armament allowed them to claim more German aircraft than all other British defenses combined. Successive modifications next turned the Hurricane into a formidable ground-attack aircraft and tankbuster in North Africa and Burma. Some versions sported two 40mm cannons or rockets in addition to 12 machine guns! By 1941 the Fw 200 Condors were threatening Britain’s sea-lanes, so expendable Hurricanes were adapted to being catapulted off of merchant ships to defend them. These were then ditched after usage. By 1942 a navalized version, the Sea Hurricane, had also been developed. Hurricanes saw active service in every theater up through 1945 before retiring as one of history’s greatest warplanes. Production amounted to 14,449 machines.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 38 feet, 4 inches; length, 34 feet, 8 inches; height, 15 feet, 10 inches

Weights: empty, 8,977 pounds; gross, 12,114 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 2,470-horsepower Bristol Centaurus radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 460 miles per hour; ceiling, 36,000 feet; range, 760 miles

Armament: 4 x 20mm cannons; up to 2,000 pounds of bombs or rockets

Service dates: 1946-1953

|

T |

he Sea Fury was the Fleet Air Arm’s ultimate piston-powered aircraft, probably the best of its class in the world. It served with distinction in Korea and counted among its many victims several MiG 15 jet fighters.

Origins of the mighty Sea Fury trace back to June 1942, when a German Focke-Wulf Fw 190 fighter mistakenly landed in England. Heretofore, radial engines had been dismissed as inferior to more complicated in-line types, but the streamlining and efficiency of the German craft surprised the British. Accordingly, the Air Ministry issued several specifications in 1943 for a lightened Hawker Tempest to equip both the Royal Air Force and Fleet Air Arm. Sir Sydney Camm then developed an entirely new monocoque fuselage, fitted it to Tempest wings, and mounted a powerful Bristol Centaurus radial engine. The resulting craft was called the Fury, a compact, low-wing fighter of great speed and strength. However, when World War II ended the RAF summarily canceled its contract, and the 100 or so Furies were

sent to Egypt, India, and Pakistan. The Royal Navy, meanwhile, continued development of the Sea Fury, which became operational in 1947. Being a naval aircraft, it was fitted with folding wings and an arrester hook. The big craft was nonetheless supremely agile for its size and popular with pilots. A grand total of 615 were ultimately acquired by the Fleet Air Arm, with several of these being farmed out to Commonwealth navies.

Commencing in 1950, several squadrons of Sea Furies participated in the Korean War (1950-1953). They carried prodigious ordnance loads, made excellent bombing platforms, and extensively flew interdiction strikes against communist supply lines. Sea Furies also destroyed more communist aircraft than any other non-American type and demonstrated their prowess by shooting down at least two MiG 15 jet fighters. Sea Furies were quickly phased out after 1953, for with the age of jets the end of propeller-driven fighters was nigh. Pakistan nevertheless operated their cherished machines until 1973.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 41 feet; length, 33 feet, 8 inches; height, 16 feet, 1 inch Weights: empty, 9,250 pounds; gross, 13,640 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 2,180-horsepower Napier Sabre II liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 435 miles per hour; ceiling, 36,000 feet; range, 740 miles Armament: 4 x 20mm cannons; up to 2,000 pounds of bombs or rockets Service dates: 1944-1951

|

T |

he Tempest was another fearsome machine unleashed by Hawker. It combined all the hard-hitting attributes of the earlier Typhoon with exceptional high-altitude performance.

Shortcomings of the Hawker Typhoon at higher altitudes led Sydney Camm to reconsider his design. The problem—unknown at the time—was compressibility, whereby air passed over airfoils at nearly the speed of sound. Because the Typhoon employed a particularly thick wing, it gave rise to constant buffeting at high speed. In 1941 Camm suggested fitting the aircraft with a thinner airfoil of elliptical design. A new engine, the radial Centaurus, was also proposed.

Design went ahead with the new Typhoon II, as it was called, which was continuously modified over time. The thinner wing necessitated the fuel tanks being transferred to the fuselage, which was lengthened 2 feet and given a dorsal spine. In light of these modifications, Hawker gave it an entirely new designation: Tempest. It was then decided to fit the

Mk V version with the tested Napier Sabre II engine because of delays with the Centaurus engine. The first deliveries of Tempest Vs were made in the fall of 1943, and these reached operational status the following summer.

In service the Tempest continued the ground – attack tradition of the Typhoon, for it easily handled 1,000-pound bombs and a host of rockets. However, because of its new wing, it also possessed superb high-altitude performance. The Tempest flew so fast that it became one of few Allied fighters able to intercept the German V-1 rocket bombs, claiming 638 of the 1,771 destroyed. The Tempest could also successfully tangle with the German Me 262 jets, destroying 20 of those formidable fighters. After the war, the Centaurus engine was finally perfected and a new version, the Tempest II, was introduced. This was the last piston-engine fighter-bomber flown by the Royal Air Force, and it served as the basis of the superb Hawker Sea Fury. A total of 1,418 Tempests of all models were constructed.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 41 feet, 7 inches; length, 31 feet, 11 inches; height, 15 feet, 3 inches Weights: empty, 8,800 pounds; gross, 13,980 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 2,180-horsepower Napier Sabre II liquid-cooled in-line engine Performance: maximum speed, 405 miles per hour; ceiling, 34,000 feet; range, 510 miles Armament: 4 x 20mm cannons; up to 2,000 pounds of bombs or rockets Service dates: 1942-1945

|

T |

he formidable “Tiffy” overcame a troubled gestation to emerge as the best ground-attack aircraft of World War II. Attacking in waves, they devastated German armored formations at Normandy and elsewhere.

In 1937 Air Ministry Specification F.18/37 stipulated a future replacement for the Hawker Hurricanes then in service. Design began that year, but intermittent problems with the Roll-Royce Vulture engine greatly prolonged its development. The prototype did not fly until May 1941, and then it was powered by the unreliable Napier Sabre I engine. The Typhoon was a low-wing monoplane and the first Hawker product featuring stressed-skin construction. It also mounted widetrack landing gear, and initial models had a cabin-type cockpit with a side door. The aircraft flew well at low altitudes but demonstrated dismal climbing capacity. However, when Focke-Wulf Fw 190 fighter-bombers began playing havoc on England’s southern coast, the Typhoon was rushed into production with minimal testing.

The first Typhoons arrived in service during the fall of 1941 with mixed results. The Sabre engine remained unpredictable, and the rear fuselage suffered from structural failure. At one point the Royal Air Force seriously considered canceling the entire project, but Hawker persisted in refining the basic design. Consequently, the airframe was beefed up and more reliable versions of the Sabre engine were mounted. By 1943 the major bugs had been eliminated, and the Typhoon found its niche as a low-altitude fighter and ground-attack craft. Being the first British aircraft to achieve 400 miles per hour in level flight, it successfully countered Fw 190 raids at lower altitudes. By 1944 Typhoons were also modified to carry two 1,000-pound bombs or a host of rocket projectiles. Attacking in waves, they proved particularly devastating against German Panzer divisions at Falaise, destroying 137 tanks in one day! They were all retired by 1945 as the most effective ground-attack aircraft of the war. A total of 3,330 had been built.

Type: Trainer; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 30 feet, 9 inches; length, 38 feet, 4 inches; height, 13 feet Weights: empty, 9,700 pounds; gross, 11,350 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 5,845-pound thrust Rolls-Royce Turbomeca Adour turbofan engine Performance: maximum speed, 645 miles per hour; ceiling, 44,500 feet; range, 317 miles Armament: none or 1 x 30mm cannon pod; up to 6,614 pounds of bombs and rockets Service dates: 1976-

|

T |

he Hawk is one of the world’s most successful jet trainers and is widely exported abroad. It can be fitted with a variety of weapons and functions as a highly capable light strike aircraft.

A 1964 air staff study predicted that the forthcoming SEPECAT Jaguar trainers would be too expensive and too few in number to meet Royal Air Force training requirements. That year specifications were issued for a cheaper yet capable trainer to replace the Gnats and Hunters then operating. At length the Hawker-Siddeley group announced its Model HS 1182, a sleek, low-wing aircraft seating two under a long tandem canopy. Suitably impressed, the RAF in 1972 placed an initial order for 176 Hawk T Mk 1s, the first of which was delivered in 1976. This relatively low-powered aircraft turned out to be surprisingly successful. The Hawk is fast, maneuverable, and easy to fly. It can also be rigged for weapons training and is fitted with a centerline cannon pod under the fuselage, and the wings employ four hardpoints capable of launching missiles.

In this capacity, the Hawk affords multimission trainer/light strike capability as much less cost than conventional jets. More than 700 have been built and are operated by seven nations.

In an attempt to exploit the Hawk’s potential as a combat type, British Aerospace (BAe, which acquired Hawker-Siddeley) in April 1977 developed a dedicated ground-attack version, the Hawk 100. It differed from earlier models in possessing a modified combat wing better suited for heavy ordnance and high-G maneuvers. First flown in 1992, it was purchased by Abu Dhabi, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Oman, and Saudi Arabia. In 1986 BAe subsequently designed the Hawk 200, which is a singleseat dedicated strike fighter for the Third World. This model exhibits a redesigned front section, a more bulbous nose housing an advanced radar, and other digital systems. As before, it offers relatively high performance and firepower at affordable prices. Thus far, only Oman and Malaysia have placed orders.

Type: Antisubmarine; Patrol-Bomber; Reconnaissance

Dimensions: wingspan, 114 feet; length, 126 feet, 9 inches; height, 29 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 86,000 pounds; gross, 192,000 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 12,140-pound thrust Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan engines

Performance: maximum speed, 575 miles per hour; ceiling, 42,00 feet; range, 5,758 miles

Armament: up to 13,500 pounds of torpedoes, depth charges, or mines

Service dates: 1969-

|

T |

he Nimrod is one of the most capable antisubmarine platforms currently in service, a union of advanced electronics with fine flying characteristics. A few also serve as secret electronic countermeasure platforms and intelligence-gatherers.

By 1964 the British Air Ministry wished to replace its Korean War-vintage Avro Shackletons with a more advanced machine for antisubmarine warfare (ASW). Specifications were initially drawn around the existing Dassault Atlantique, but the British government intervened and requested that the existing Comet 4 civilian airliner be adopted. This was an aircraft renowned for good cruising and flying abilities and had been in Royal Air Force service since 1955 as a transport. Accordingly, in 1967 the first Nimrod prototype was flown. It shared some similarities with its forebears but, being fitted with a lengthy bomb bay, the fuselage acquired a “double-bubble” cross-section. The Nimrod also sports an electronic “football” atop the rudder and a long magnetic anomaly detector boom jutting from

the tail. Consistent with its ASW mission, the plane carries a variety of depth charges, sonobuoys, homing torpedoes, and related detection gear. A typical patrol might last up to 12 hours, and the Nimrod can extend its loiter time over a target by up to six hours by shutting down as many as three of its engines! A total of 45 Nimrods (named after the great hunter of the bible) have been acquired and are subject to constant electronic upgrades.

In 1971 three aircraft were deflected from the ASW program to be outfitted as Nimrod R Mk 1s. These are highly sensitive, top-secret intelligencegathering platforms of which much is said but little is known. They are distinguished from other airplanes by the absence of radar tailbooms and the presence of external fuel tanks on the leading edges. In the hands of No. 51 Squadron, they were highly active during the 1982 Falkland Islands War with Argentina and garnered a battle citation. Both Nimrod versions are expected to actively serve well into the twenty-first century.

Type: Fighter; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 36 feet, 1 inch; length, 27 feet, 6 inches; height, 10 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 3,247 pounds; gross, 4,189 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 750-horsepower BMW VI liquid-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 205 miles per hour; ceiling, 25,260 feet; range, 345 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns; 120 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1935-1943

|

T |

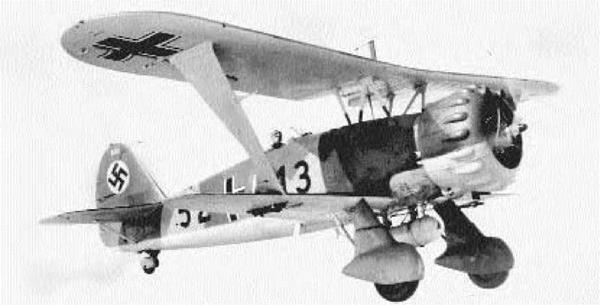

he shapely He 51 was the first Luftwaffe fighter constructed since the Armistice of 1918 and a potent symbol of German rearmament. It was outclassed as a dogfighter in Spain but helped pioneer the ground-attack tactics used in World War II.

Ernst Heinkel formed his own company in 1922 following the liquidation of the old Hansa-Bran – denburg firm. He was ostensibly engaged in constructing floatplanes and civilian craft, but as the political climate in Germany hardened, his designs more and more resembled military aircraft. As Germany embarked on national rearmament in 1933, Heinkel was directed to develop a new fighter plane—the first since World War I. He responded with the He 51, an outgrowth of his earlier He 49 civilian machines. It was a handsome, single-bay biplane of mixed wood and metal construction, covered with fabric. It featured an attractive pointed cowl and streamlined, spatted landing gear. Flight tests revealed the He 51 to be fast and nimble, so it was accepted for service in 1935. That same year,

the existence of the previously secret Luftwaffe was defiantly announced to the world.

In service the He 51 proved somewhat troublesome. It was unforgiving by nature, and a tendency to “hop” while landing contributed to several accidents. Nonetheless, it was the only aircraft on hand when the Spanish Civil War erupted in 1936, and Hitler dispatched large numbers of them piloted by German “volunteers” of the Kondor Legion. Initial reports were favorable, for the He 51 easily dispatched a host of older French and British machines. But Heinkel’s fighter was badly outclassed by the Russian-supplied Polikarpov I 15 and sustained heavy losses. Thereafter, it became necessary to restrict He 51s to ground attack, a role in which they performed admirably and helped pioneer the close-support tactics made famous in World War II. The introduction of Arado’s Ar 68 in 1937 led to its withdrawal from frontline service. This neat biplane spent its last days as a training craft up through 1943. A total of 725 were built.

Type: Patrol-Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 77 feet, 9 inches; length, 57 feet, 1 inch; height, 23 feet, 3 inches

Weights: empty, 13,702 pounds; gross, 19,842 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 660-horsepower BMW VI liquid-cooled in-line engines

Performance: maximum speed, 134 miles per hour; ceiling, 11,480 feet; range, 1,087 miles

Armament: 3 x 7.92mm machine guns; 2,205 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1932-1943

|

O |

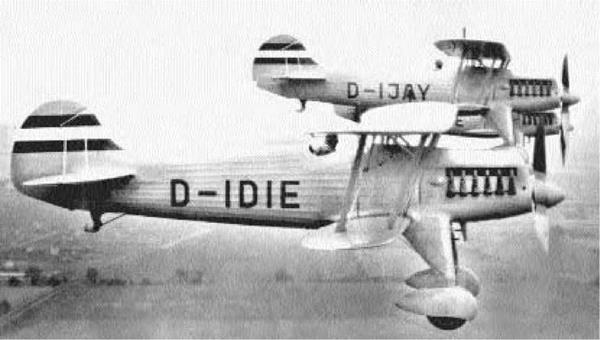

ne of the first aircraft acquired by the Luftwaffe, the big He 59 was a versatile machine capable of many functions. It saw active service in World War II and even helped stage daring commando missions.

The He 59 was originally designed in 1930 as part of a clandestine program to equip Germany with military aircraft. Although posited as a twin-engine maritime rescue craft, it was in fact intended as a reconnaissance bomber capable of serving off both water and land. The first prototype, designed by Reinhold Mewes, flew in 1931 with large “trousered” wheel spats, but subsequent versions were all fitted with twin floats. Like many aircraft of this era, the He 59 was of mixed construction, having a fuselage made from steel tubing, wings of wood, and entirely covered by fabric. The bomber seated a crew of four comfortably and was wellarmed with machine guns in nose, dorsal, and ventral positions. Both flight and water performance were adequate, so the German government ordered 105 machines built in several versions.

The He 59 first saw combat during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1938), where it functioned as a patrol-bomber. At night the big craft would glide over an intended target unannounced, then drop bombs upon astonished defenders. He 59s were pushing obsolescence in 1939 when World War II erupted, but for many months the lumbering craft performed useful work. Most He 59s equipped coastal reconnaissance groups, but others operated with the Seenot – dienststaffeln (air/sea rescue squadrons). These craft were conspicuously painted white with large red crosses in the early days of the war and left unmolested by Royal Air Force fighters—until they were discovered directing German bombers by radio. But the most important service of the He 59 was in transporting Staffel Schwilben (special forces). On May 10, 1940, a dozen He 59s landed in the Maas River, Rotterdam, and disgorged 120 assault troops, who paddled ashore and stormed the strategic Willems bridge. They were all finally retired by 1943.

Type: Reconnaissance; Light Bomber; Liaison

Dimensions: wingspan, 48 feet, 6 inches; length, 38 feet, 4 inches; height, 10 feet, 2 inches

Weights: empty, 5,723 pounds; gross, 7,716 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 750-horsepower BMW VI water-cooled in-line engine

Performance: maximum speed, 220 miles per hour; ceiling, 19,685 feet; range, 500 miles

Armament: 1 x 7.92mm machine gun; up to 661 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1933-1939

|

W |

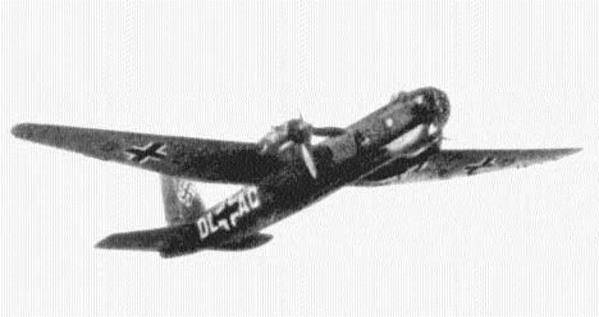

hen it appeared in 1932, the futuristic He 70 was a marvel of streamlining and aerodynamic innovation. It enjoyed a relatively short service life but set significant trends in aircraft design for years to come.

With the acquisition of Lockheed Orion aircraft in 1932, Swiss Air became Europe’s fastest passenger carrier. This development alarmed the German national airlines, Deutsche Lufthansa, which then approached Heinkel for a new and even faster aircraft. It fell upon two brothers, Siegfried and Walter Gunter, to conceive one of the most advanced yet beautiful aircraft of the decade. Christened the He 70 Blitz (Lightning), this was a single-engine, low-wing monoplane of extremely clean, aerodynamic lines. The broad wings were elliptically shaped and sported retractable landing gear. The fuselage, meanwhile, was oval in cross-section and semimonocoque in construction with a low-profile windscreen to cut drag. Moreover, the engine utilized ethylene glycol as a coolant, which allowed a smaller radiator and overall frontal area. To reduce

drag even further, the stressed metal skin was secured in place by countersunk riveting. The net result was a strikingly beautiful airplane that anticipated the features of monoplane fighters by several years.

In test flights the He 70 easily outpaced the He 51 biplane, a craft possessing a more powerful engine, while weighing half as much! In 1933 the prototype alone went on to establish eight world speed records and bolstered Lufthansa’s reputation as the fastest airline on the continent. Naturally, such high performance caught the military’s attention, so several models were built for the Luftwaffe. These included both light attack and reconnaissance versions, 18 of which served in the Spanish Civil War. Flown by the Kondor Legion, they performed with distinction and easily outflew all opposition. A total of 296 He 70s had been manufactured by the time production ceased in 1937, and most were employed as courier/liaison craft. Heinkel’s masterpiece enjoyed a short, undistinguished career but is best remembered as a harbinger of things to come.

Type: Medium Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 74 feet, 1 inch; length, 53 feet, 9 inches; height, 13 feet, 1 inch Weights: empty, 19,136 pounds; gross, 30,865 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 1,350-horsepower Junkers Jumo liquid-cooled in-line engines Performance: maximum speed, 227 miles per hour; ceiling, 21,980 feet; range, 1,212 miles Armament: 4 x 7.92mm machine guns; 1 x 20mm cannon; up to 4,409 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1936-1945

|

T |

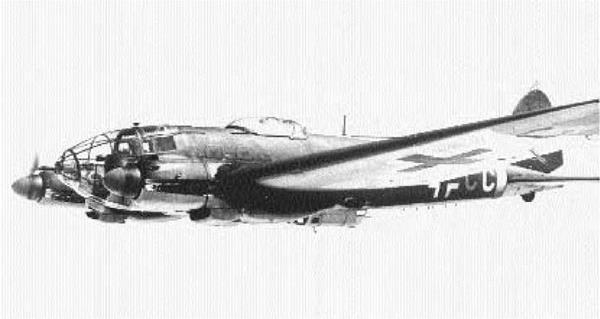

he long-serving He 111 was a mainstay of the Luftwaffe bomber force, as well as a successful tactical machine. However, the lack of a suitable successor kept it in production long after becoming obsolete.

In the early 1930s the Germans resorted to clandestine measures to obtain modern military aircraft. Accordingly, the Heinkel He 111 had been ostensibly designed by Walter and Siegfried Gunter as a fast commercial transport for the German airline Lufthansa. Like the famous He 70, it was a radically streamlined, all-metal aircraft with smooth skin and elliptical wings. Early models, both civil and military, also featured a stepped cabin with a separate cockpit enclosure. The new bomber proved fast and maneuverable, so in 1937 several were shipped off to the Spanish Civil War for evaluation. Not surprisingly, the He 111s outclassed weak fighter opposition and flew many successful missions unescorted. Thereafter, German bomber doctrine called for fast, lightly armed aircraft that could survive on speed alone. That decision proved

a costly mistake in World War II. In 1939 the Model P arrived, introducing the trademark glazed cockpit canopy that appeared on all subsequent versions. When war finally erupted that fall, the fast, graceful Heinkels constituted the bulk of Germany’s bomber forces.

After deceptively easy campaigning in Poland and France, He 111s suffered heavily at the hands of British fighters during the 1940 Battle of Britain. This caused later editions to carry more armor and weapons, which in turn degraded performance. And because its designated successor, the He 177, proved a failure, the He 111 was kept in production despite mounting obsolescence. For the rest of the war, the lumbering craft functioned as torpedo – bombers, cable-cutters, pathfinders, and glider tugs. A final variant, the He 111Z (for Zwilling, or “twin”), consisted of two bombers connected at midwing with a fifth engine. These were designed to tow massive Messerschmitt Me 323 Gigant gliders into action. By war’s end, more than 7,000 of these venerable workhorses had been produced.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 72 feet, 2 inches; length, 56 feet, 9 inches; height, 21 feet, 8 inches Weights: empty, 11,684 pounds; gross, 22,928 pounds Power plant: 2 x 865-horsepower BMW 132N radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 220 miles per hour; ceiling, 18,045 feet; range, 2,082 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns; 2,765 pounds of bombs, torpedoes, or mines Service dates: 1937-1945

|

T |

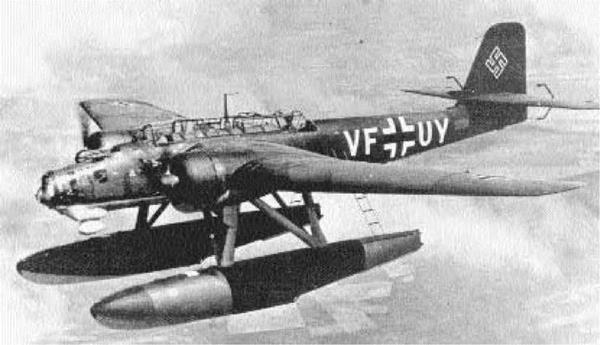

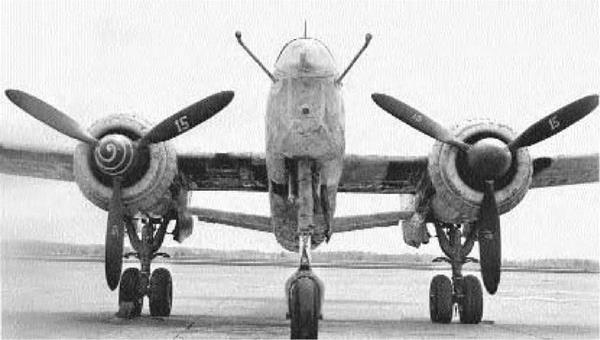

he Heinkel He 115 was the Luftwaffe’s most versatile floatplane reconnaissance craft. It performed so successfully that production was resumed in midwar.

In 1936 the prototype He 115 was flown as the successor to the aging He 59. It was a standard, allmetal, midwing monoplane whose broad wing possessed tapering outer sections. A crew of three was housed in an elongated greenhouse canopy, and the craft rested upon two floats secured in place by struts. The prototype was fast, handled well, and quickly broke eight floatplane records in 1938. Such impressive performance resulted in orders from overseas, and both Norway and Sweden purchased several machines. The He 115 also entered production with the Luftwaffe Seeflieger (coastal reconnaissance forces). In 1939 the B model appeared, featuring greater fuel capacity and reinforced floats for operating in snow and ice.

When World War II commenced, the He 115s partook of routine maritime patrolling and mining of

English waters. They were the first German craft adapted to drop the new and deadly acoustic sea mines from the air, which inflicted great damage upon British shipping. They also proved quite adept at torpedo-bombing and as long-range reconnaissance craft. Curiously, the 1940 invasion of Norway found He 115s closely engaged on both sides of the conflict. The six Norwegian machines put up stout resistance, with three survivors and a captured German machine escaping to Britain. These were subsequently given German markings and employed for clandestine operations ranging from Norway to Malta. These activities were subsequently suspended after 1943 for fear of attacks by Allied aircraft. The high point of He 115 operations with German forces occurred in 1942, when they shadowed ill-fated Convoy PQ-17 in the Arctic Circle and assisted in its destruction. Production of He 115s ceased in 1941, but their services were so highly regarded that it resumed in 1943! A total of 450 machines were built, and most performed capably up to the end of hostilities.

Type: Heavy Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 103 feet, 1 inch; length, 72 feet, 2 inches; height, 20 feet, 11 inches

Weights: empty, 37,038 pounds; gross, 68,343 pounds

Power plant: 4 x 950-horsepower Daimler-Benz 610 A-1 in-line engines

Performance: maximum speed, 304 miles per hour; ceiling, 26,245 feet; range, 3,417 miles

Armament: 6 x 7.92mm or 13mm machine guns; 1 x 20mm cannon; 2,205 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1942-1945

|

T |

he He 177 was the Luftwaffe’s sole heavy bomber type of World War II, but it remained a minor player. Considering the quantity of resources squandered, the Greif (Griffon) was Germany’s most conspicuous aeronautical failure.

The 1936 death of General Walter Wever, the Luftwaffe’s vocal proponent of heavy bombers, seriously compromised Germany’s attempt to obtain strategic weapons. Two years later the Air Ministry contacted Heinkel to build a long-range bomber, despite that firm’s unfamiliarity with such craft. The prototype He 177 Greif emerged in 1939 as a modern, all-metal, high-wing monoplane. Curiously, it was propelled by four engines, but to reduce drag two power plants were coupled together in each nacelle, attached to a single propeller. As an indication of how disoriented German war planners had become, the giant craft was also expected to be capable of dive-bombing! Consequently, the much-maligned He 177 suffered a litany of insurmountable technical problems, especially engine fires. Several

prototypes were built and crashed before the first He 177s could become operational in March 1942.

From the onset, the Greif was an unsatisfactory aircraft, one that wasted huge quantities of scarce resources and manpower. Operations on the Eastern Front proved sporadic owing to the constant engine fires, as well as structural failure arising from dive-bombing attacks. Crews, although admiring the fine flying qualities of the craft, came to regard it as the “Flaming Coffin.” In the West, He 177s conducted Operation Steinbock, also known as the “Little Blitz” of January 1944. Those few machines able to get airborne climbed to their maximum height over Germany, then commenced long, shallow dives over London. Ensuing speeds of more than 400 miles per hour prevented their interception but did little to ensure bombing accuracy. With greater emphasis on research and development, the He 177 might have evolved into a formidable weapon. As it was, most were abandoned by late 1944 because of fuel and parts shortages. Around 1,000 were built.

Type: Night Fighter

Dimensions: wingspan, 60 feet, 8 inches; length, 50 feet, 11 inches; height, 13 feet, 5 inches

Weights: empty, 25,691 pounds; gross, 33,370 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 1,800-horsepower Daimler-Benz 603E radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 416 miles per hour; ceiling, 41,665 feet; range, 1,243 miles

Armament: 6 x 30mm cannons; 2 x 20mm cannon

Service dates: 1944-1945

|

T |

he mighty Uhu was Germany’s best operational night fighter of World War II. Fast and heavily armed, it was one of few aircraft capable of engaging the formidable British Mosquito on equal terms.

Ernest Heinkel began developing the He 219 in 1940 as a private venture to create a long-range fighter-bomber. The Luftwaffe leadership expressed no interest in the project until 1941, when large-scale night bombing by the Royal Air Force commenced. They then requested Heinkel to modify his design into a dedicated night fighter, and the prototype flew in 1943 with impressive results. The new He 219 was a big, high-wing, twin-engine monoplane with a nose – wheel and double rudders. It was also the first production airplane to be equipped with ejection seats. The crew sat back-to-back under a spacious canopy that granted excellent visibility. Moreover, the armament of four cannons was buried in the fuselage belly so that muzzle flashes did not blind the operators. Flight tests were concluded after a preliminary order for 300 machines was received. The first

He 219s, called Uhu (Owl) by their crews, were initially deployed at Venlo, Holland. On his first nighttime sortie, Major Werner Streib shot down five Lancaster bombers, and after only six operational sorties the unit tally stood at 20 victories. Six of these were the heretofore unstoppable Mosquitos.

Production of the He 219 commenced in 1943 but remained slow and amounted to only 288 aircraft. This proved fortunate for the Allies, as successive versions of the Uhu grew increasingly lethal to bombers. One reason was adoption of the Schrage Musik (“slanted music,” or jazz) installation, whereby heavy cannons were mounted on top of the fuselage at an angle. This enabled He 219s to slip below the bomber stream in level flight and pour heavy fire directly into their bellies. The handful of He 219s constructed and deployed were responsible for thousands of Allied casualties. But in 1944 General Edward Milch canceled the entire project in favor of the unsuccessful Focke-Wulf Ta 154 and Junkers Ju 388 projects.

Type: Dive-Bomber; Light Bomber

Dimensions: wingspan, 34 feet, 5 inches; length, 27 feet, 4 inches; height, 10 feet, 6 inches

Weights: empty, 3,361 pounds; gross, 4,888 pounds

Power plant: 1 x 880-horsepower BMW 132Dc radial engine

Performance: maximum speed, 214 miles per hour; ceiling, 29,530 feet; range, 530 miles Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns; 440 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1936-1944

|

T |

he antiquated-looking Hs 123 was the Luftwaffe’s first dive-bomber. Although eclipsed by the legendary Ju 87 Stuka, it rendered impressive service during World War II and gained a reputation for toughness.

One of the first requirements espoused by the newly established Luftwaffe in 1933 was the need for dive-bombers. Henschel consequently fielded the Hs 123, a single-bay sesquiplane (two wings of unequal length) with an open canopy, a large radial cowling, and streamlined, spatted landing gear. The craft was of all-metal construction, save for fabric – covered control surfaces, and the pilot enjoyed excellent all-around vision. Noted pilot Ernst Udet test-flew the prototype in the spring of 1935 with great success, and the government determined to acquire it as an interim type until the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka became available. Accordingly, the first Hs 123s rolled off the production lines in 1936 and were sent to Spain for evaluation under combat conditions. At high altitude they proved vulnerable to attacks by Russian-supplied Polikarpov I 15 fighters,

so they were subsequently employed as ground-attack aircraft. Here the Hs 123s enjoyed remarkable success for such an allegedly obsolete design, dropping bombs and strafing enemy troops with great precision. By 1938, however, the Stuka became the standard Luftwaffe dive-bomber, and the handful of Hs 123s still in service equipped only one squadron.

The onset of World War II in September 1939 garnered additional luster for the little biplane’s reputation. They served with great success in the Polish campaign where, flying low with throttles wide open, their deafening howl terrorized men and horses alike. The craft also established a legendary reputation for absorbing tremendous damage. Hs 123s then bore prominent roles in the 1940 campaigns in Belgium and France, where they readily broke up concentrations of troops and tanks. Despite the growing obsolescence of its equipment, the squadron distinguished itself further during the Balkan and Russian campaigns of 1941. They were finally withdrawn from combat in 1944, one of the world’s great fighting biplanes.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 46 feet, 7 inches; length, 31 feet, 11 inches; height, 10 feet, 8 inches

Weights: empty, 8,400 pounds; gross, 11,574 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 700-horsepower Gnome-Rhone 14M radial engines

Performance: maximum speed, 253 miles per hour; ceiling, 29,540 feet; range, 429 miles

Armament: 2 x 7.92mm machine guns; 2 x 20mm cannons; up to 551 pounds of bombs

Service dates: 1942-1945

|

D |

espite its small size, the Hs 129 was the most successful German tankbuster of World War II. It flew persistently throughout the Eastern Front, exacting a heavy toll from Russian armor.

One lesson learned from the Spanish Civil War was the need for dedicated ground-attack aircraft. Consequently, in 1937 the German Air Ministry issued specifications for a well-armored, single-seat machine powered by two engines. Henschel responded in 1939 with a unique prototype designed by Friedrich Nicolaus. It was an all-metal, midwing craft with an extremely blunt nose and wings possessing a tapered trailing edge. Moreover, the relatively small cockpit was shielded by bulletproof glass and so cramped that several engine instruments were by necessity relocated to the inboard engine nacelles! Power was provided by two Argus As 410A-1 inverted in-line engines. Test flights, unfortunately, were disappointing, as the Hs 129 proved underpowered and sluggish. The Luftwaffe authorized several preproduction examples as a

hedge, but they were subsequently passed off to the Romanian air force.

By 1940 Nicolaus had sufficiently revamped his creation, the Hs 219B, and submitted it for flight trials. This time it was powered by captured French Gnome-Rhone 14M radial engines and assisted in flight by electric trim tabs. Results were better, so the Hs 129B entered into production; 870 were eventually built. These craft also were fitted with an amazing array of heavy weapons for antitank warfare, particularly along the Eastern Front. Eventually, Hs 129s proved themselves the scourge of Soviet armor, and during the 1943 engagement at Kursk they destroyed several hundred tanks. Attempts were then made to upgrade the Hs 129s firepower, and several were fitted with a huge 75mm Pak40 antitank gun. This weapon could destroy a tank from any angle, but it recoiled so strongly that the Hs 129s usually stalled. These “Flying Can-openers” remained the bane of Russian armor until the end of 1944, when most were grounded due to lack of fuel and spare parts.

|

Dimensions: wingspan, 29 feet, 6 inches; length, 52 feet, 3 inches; height, 11 feet, 9 inches Weights: empty, 13,658; gross, 24,048 pounds

Power plant: 2 x 4,850-pound thrust Rolls-Royce Orpheus turbojet engines Performance: maximum speed, 675 miles per hour; ceiling, 40,000 feet; range, 898 miles Armament: 4 x 30mm cannons; 54 unguided rockets in a retractable pack; 4,00 pounds of bombs Service dates: 1968-1985

|

T |

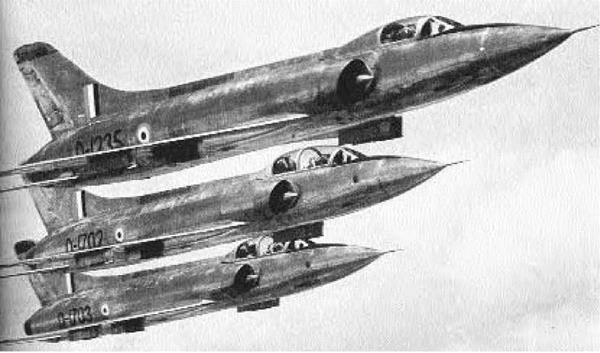

he Marut was the first and only indigenous jet fighter constructed in India. Although designed by the famous Dr. Kurt Tank, it was continually hindered by lack of adequate power and so never fulfilled its obvious potential.

In 1950 the newly independent government of India sought to break its traditional reliance on European aircraft by developing warplanes of its own. Necessity required them to replace the aging fleet of Dassault Mysteres and Ouragans then in service as well. In 1956 Hindustan Aircraft Limited tasked a German engineering staff headed by the brilliant Dr. Kurt Tank, formerly of Focke-Wulf, with designing a multipurpose jet fighter with supersonic performance. With the aid of Indian engineers, a full-scale glider was tested in 1959, followed two years later by a functioning prototype. The new HF 24 Marut (the Wind Spirit in Hindu mythology) was a sleek, twin-engine design with a highly pointed profile and a low-mounted wing. It flew in 1961 powered by two Bristol-Siddeley Orpheus 703 turbojets, but nearly a year lapsed before a

second prototype emerged. In 1964 16 preproduction Maruts followed, but they were not equipped with afterburners. This deficiency ensured that HF 24s would never approach Mach 2. Work continued on a succession of different power plants and a locally designed afterburner for several years, and it was not until 1967 that full-scale production of the HF 24 resumed. This concluded after 145 machines were built; an additional 18 Mk IT two-seat trainers were added in 1970.

Despite its low power, the Marut handled fine and proved a capable fighter-bomber when so armed. Their combat initiation occurred during the 1971 war with Pakistan and three squadrons acquitted themselves well with few losses. After this a variety of new engines was fitted, none of which nudged the aging HF 24 toward supersonic speed. The scheme was ultimately abandoned, and by 1995 most Maruts were replaced in service by MiG 23s and SEPECAT Jaguars. The HF 24s were fine aircraft, but their passing confirms India’s continuing dependence on foreign technology.