Projects Mercury and Gemini

NASA quickly captured the public imagination with Project Mercury. Amid a blaze of publicity, seven pilots (all men) were chosen to be America’s first astronauts. Alan B. Shepard was the first American to fly into space on May 5, 1961, squeezed inside a cramped Mercury capsule launched by a Redstone rocket. On February 20, 1962, John H. Glenn, became the first U. S. astronaut to orbit Earth.

As the Mercury program continued, NASA scientists also were engaged in a range of unmanned space activities-sending probes to the Moon and to Mars, for example. Public attention, however, focused on the “space race” between the Soviet Union and the United States. The declared U. S. intention, as stated in May 1961 by President John F. Kennedy, was to land men on the Moon and bring them back safely. This was an immense challenge, and many people doubted NASA could achieve the president’s goal.

After the completion of the Mercury program, NASA progressed to two-person flights in Earth’s orbit, using the larger Gemini spacecraft. Gemini flights provided valuable experience in space piloting, rendezvous and docking, extra-vehicular activity (space walks), and reentry and splashdown techniques.

О President John F. Kennedy (center, facing right and wearing sunglasses) toured NASA’s facilities at Cape Canaveral in Florida in 1962. The Cape was the launch site of the Apollo missions. Today, NASA’s facilities at the Cape and elsewhere have expanded greatly.

О President John F. Kennedy (center, facing right and wearing sunglasses) toured NASA’s facilities at Cape Canaveral in Florida in 1962. The Cape was the launch site of the Apollo missions. Today, NASA’s facilities at the Cape and elsewhere have expanded greatly.

Apollo

The Moon landing program, using the three-person Apollo spacecraft, was pursued with enormous energy at a staggering cost of over $25 billion. Apollo has been compared, in terms of national effort, to digging the Panama Canal or making the first atomic bomb during World War II. In 1967, the Apollo program survived the tragic setback of a fire inside an Apollo capsule in which three astronauts died. The program triumphed in 1969 with the historic landing of two Apollo 11 astronauts, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, on the Moon.

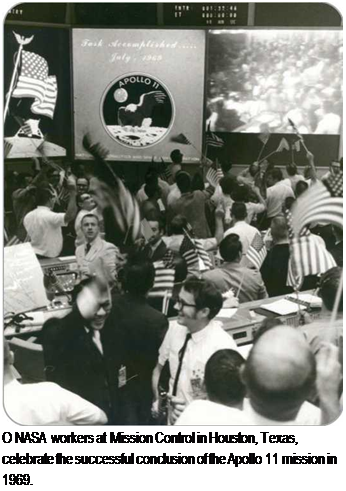

Everything NASA did was very public. During the Apollo 11 spaceflight and later Apollo Moon landings for example, people all over the world were enthralled by television coverage of the launches and splashdowns, directed from NASA nerve centers that included the Cape Canaveral launch site in Florida and the

Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas. Television audiences were able to see control room staff at work and talking to the astronauts, and they could watch pictures beamed directly from the Moon. NASA space jargon used by the flight controllers, such as “T minus 30 and counting” have since passed into common usage.

Five more lunar landings followed that of Apollo 11. NASA managed to avert disaster when the Apollo 13 mission of April 1970 went seriously wrong. On this mission, the Moon landing had to be canceled after an oxygen tank exploded midway through the outward flight. The three astronauts flew around the Moon and, despite severe power problems, returned safely to Earth. Their safe return was a tribute to NASA’s ability to adapt its technology to cope with the unexpected. In total, twelve astronauts walked on the Moon during the

six Apollo lunar landings, which marked the highpoint of NASA’s success.

six Apollo lunar landings, which marked the highpoint of NASA’s success.