INTRODUCTION

|

V |

on Richthofen was tar from a natural born pilot but he learned rapidly and became highly proficient. Over the years many people have tried to present him as a man who could not nave achieved his 80 recorded victories without the support of his Jasta pilots, two of whom were upposedly detailed specifically to protect his tail while he made the kills. Also that he took credit for other pilots’ claims or took a share in kills credited to the Jasta or Jagdgeschwader. This is fir from the truth; such a man would not have been held in such high esteem by his men who would certainly have not celebrated his memory for many years after WW1 at the annual gathering of ‘The Old Eagles’. Certainly he flew at the head of his unit and it was his job to make the first attack, but this was the German system, this is how the fighting units acted, it was nothing specially attributed to von Richthofen’s personal way of doing things. He achieved his remarkable score in just 18 months of front line combat duty by pure ability and shooting expertise.

In the years between 1918 and 1997 there have been numerous attempts to resolve the contradictions, both apparent and real, concerning events that occurred on 21 April 1918: namely, the day that Rittmeister Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen was killed in action.

In the late 1920s, Floyd Gibbons, an American journalist, wrote what is still justly believed by many historians to be the best biography of the German air. ace yet published, The Red Knight of Germany. To describe the events surrounding the death of the Baron he used information which was provided to him through ‘official channels’ (mostly Air Ministry in London) and which, by no fault of his own. he accepted in good faith.

He found that under the 50-year rule, records were sealed until 1969. The sealing had considerable justification for the files, which the present authors have examined, include personal character evaluations and so on. Air Ministry offered to arrange for someone to study the records and to provide Gibbons with a summary of the information requested. The information that he subsequently received unfortunately contained many serious errors. It is to be found at the Public Records Office. Kew, London, where it has been filed together with a resume of an interview with Captain Roy Brown some years

later, (see Appendix D)

Prior to Gibbons’ book being published it was serialised in the American magazine Liberty. His descriptions of the events of 21-22 April, in both the serial and the book, were, therefore, based upon flawed information. However, in some of the subsequent reprints of the book, a few of the errors were corrected, although one or two then introduced further errors. It appears that rather than consult the Air Ministry. Gibbons would have done much better to have travelled to Canada and interviewed Brown himself.

In short, Gibbons’ honest, best efforts were seriously flawed from the outset and had a ‘snowball effect’ as a Liberty copywriter would later insert many of the flaws into his dramatisation of Brown’s wartime service recollections which were published under the title My Fight with Richthofen in November 1927. By chance, an anonymous description of the air battle on 21 April 1918 was making the rounds at the time. It had more flaws in it than facts but read convincingly and phrases from it, which are recognisable, were also inserted. Doubtless this copywriter was doing his best to make the story interesting by filling in details which Brown had ‘apparently’ omitted. (See Appendix B)

The reader, furthermore, was led to believe that Brown himself had dictated every word. However, many years later the magazine editor admitted that the text had been ‘heavily edited’ prior to publication. (See Appendix E)

Following the diffusion around the world of the two stories, letters from participants and witnesses of the actual event began to reach magazines and newspapers. These called attention to serious omissions and alleged the inclusion of pure invention in both stories. Into the latter case fell the description, one given in great detail, of the roles played by two of 209 Squadron personnel, Major С H Butler (who did not lead his unit in the air that day), and Lieutenant FWJ Mellersh, who had landed and was at Bertangles aerodrome at the time he was supposed to have been seen at the crash site.

People in many countries took an interest in the matter but unfortunately some newspapers, even as far away as Australia (who in any event knew some of their Anzac readers would have a vested interest), saw that the creation of a ‘controversy’ would increase circulation. In one known case, a key letter which would have settled one aspect once and tor all. was, for that very reason, not published! On a private level, some people began corresponding with surviving participants and eye-witnesses. However, with the coming of WW2 interest understandably declined. The letters disappeared into filing cabinets and in many cases were later thrown away upon the death of the correspondent.

In recent years one such collection from the 1930s came to light in England and by a chain of lucky circumstances it was sent to the present authors for study. The collection has great importance as memories at that period had only to go back some 20 years and personal recollections were less likely to have unintentionally been influenced by the statements and writings of others post WW2. In addition the collection of information gathered over several decades by the late Bill Evans, who lived in Cleveland, Ohio until his death in 1996, also had interesting items in it.

The first collection, circa 1937-39, was assembled by a young man, John Column, who as an RAF navigator in WW2 was to die in action over Germany in 1942. His approach was to advertise in newspapers asking for people to write to him. One of those who replied, provided a definite location for Brown’s aerial attack on the Baron. What was interesting about this collection was that the majority of contributors were not the same as those contacted by later authors such as Carisella and Titler.

Some time after WW2 three Americans took a similar interest and approach. After years of research, the late Pasquale (Bat) Carisella published П7/С Killed the Red Baron in 1969 and Dale Titler published The Day the Red Baron Died in 1970. The third author, Charles Donald, published several articles but no book. All three managed to contact participants and witnesses. The copious correspondence which followed tilled filing cabinets with letters, and boxes with audio tapes. Donald and Carisella also achieved collections of artefacts ranging from the silk scarf, goggles and belt worn by von Richthofen at the time of his death, to pieces of Fokker Dr. I Triplane 425/17, factory serial number 2009, which he was flying. Pat Carisella’s efforts included a journey to the field where the Baron’s life ended and to the cemetery where he was first buried. He was even invited to the 50th Anniversary of ‘The Old Eagles’; the surviving members of Jagdgeschwader Nr. l. known to the British by the nickname—‘The Flying Circus’.

The origin of the name Flying Circus was that the unit’s function was one of being able to move en-masse to various sectors behind the front in order to bring a large number of aeroplanes to support offensive or defensive actions. Reference has also been made to the aircraft colour schemes, but this is secondary to the main reason for the name.

To the present authors a most interesting point is the large number of witnesses who came forward or who were located and agreed to participate. Combining the five above-cited cases, the total is around 250, and the overlap, especially of Columns 1930s people, is quite small. The size of the various units of the British Fourth Army, commanded by General Sir Henry Rawlinson, which were stationed along the Morlancourt Ridge, on the Somme, is a matter of record. From this it can be adduced that the English and Australian soldiers, from private to general, who witnessed either some or the greater part of the action which culminated in the tall of the Baron, numbered approximately 1,000. This means that close to one quarter of the witnesses can be shown to have testified in private enquiries of which a record still remains.

For any one person standing on the ground to have followed the entire sequence of events without a gap of some sort was impossible. Wherever any observer stood, some part of the action was hidden from his particular view by cloud, mist or some geographical feature such as a forest and the Ridge itself. Probably the best overall view was obtained by one of Captain Brown’s colleague flight commanders who watched the entire aerial action from above. A full account is provided in DaleTitler’s book.

From the German side, three artillery observers and two fighter pilots from von Richthofen’s staff’d also saw significant parts of the fight. The new information obtained by the present authors confirms a statement made by one of the pilots which until now had not been given much credence.

The four private enquiries mentioned above concentrated on testimony from England, Germany, Australia and the USA. Another source, Canada, although occasionally mentioned, was not explored. The Canadian evidence was brought to our attention by Frank McGuire, a former historian at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. He kindly provided a number of Canadian newspaper clippings on Captain Brown. These revealed that about one year after Roy Brown had returned to Canada he officially inaugurated a

Richthofen exhibition in a military club in Toronto (which is still on display), and that for some time afterwards wherever he travelled on business he was greeted by the local press which rarely failed to enquire about his celebrated victory over Germany’s top ranking air ace. Roy Brown’s words were thereby recorded for posterity many times over and, when taken together with the text of the plaque which graced the exhibition, provide evidence which is ‘old’ by the calendar, but ‘new’ to most of the public, and of enlightening content.

An unintended off-shoot of checking the new information against old documents was the revelation of what appears to be the key to the puzzle as to why Roy Brown wrote TWO Combats in the Air reports, both dated 21 April 1918.

Using 1918 army maps and the new information, the present authors, one of whom has fifty years experience as an aircraft pilot, made a high level and a low level flight following the path down the River Somme taken by Lieutenant W R May as he was being chased by the Baron. The ground speed of the low level flight was the same as that of its 1918 predecessor. From this exercise the authors believe that they may have stumbled across the explanation of how the Baton came to violate his own strict rules against flying low down over enemy territory. During low level flying a pilot can easily lose track of his exact position and confuse one spot with another, or in the case of von Richthofen on the day in question, one partly demolished village and bend in a river with another.

The author-pilot also held long conversations with two people who have built and flown replica

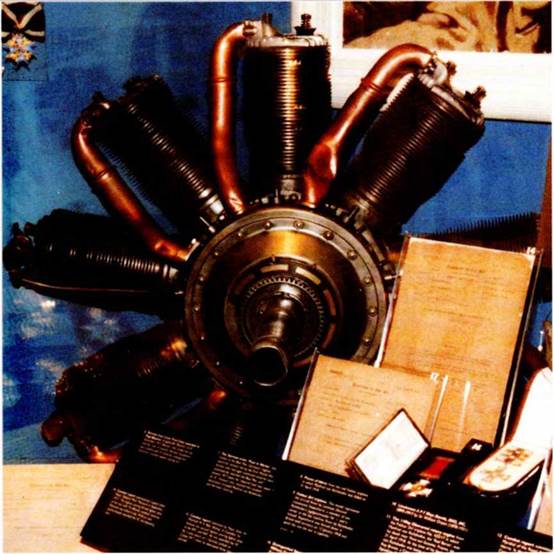

Fokker Dr. I Triplanes. One of them was exact to the point of having a 110 hp LeRhone rotary engine and was flown about thirty times each year for several years by the late Cole Palen of New York. The flight characteristics of these aircraft, he learned, are considerably different from those which both he and the general public had been led to believe. The differences contribute to the misrepresentation of some of the eye-witness evidence. By design intent the Fokker Triplane did not have inherent stability. This made it extremely manoeuvrable in combat as it did not resist sudden changes of attitude desired by the pilot. The most obvious indication of this feature is the complete absence of wing dihedral. The disadvantage was that the Triplane would not automatically recover from any upset caused by strong wind or turbulence; the pilot had to restore it to level flight. This made the aircraft appear to be unsteady when flying through zones of turbulence. However, it was not a difficult aeroplane to fly, or land, provided that it was landed directly into the wind.

The following photographs serve to demonstrate how old information may not necessarily be well-known or even believed. The subjects are still in place today and may be seen by anyone who cares to do so. Two of them have been there for over 70 years and their condition bears heavily upon a correct understanding of the manner of the Baron’s death. The reader is recommended to make a most careful examination of the photographs of the seat and the engine.

|

Above: The Le Rhone engine from von Richthofen’s Triplane 425/17. It was obviously not rotating at the time of impact.

Right: Despite several references to the contrary, Manfred von Richthofen is buried in Wiesbaden Municipal Cemetery, in a family plot together with his brother Boiko, his sister Elisabeth and her husband. There is also a memoriam plaque to brother Lothar, who is buried at Schweidnitz together with their father. In the photo Madame Niedermeyer places a flower on Manfred’s headstone.

Right: Despite several references to the contrary, Manfred von Richthofen is buried in Wiesbaden Municipal Cemetery, in a family plot together with his brother Boiko, his sister Elisabeth and her husband. There is also a memoriam plaque to brother Lothar, who is buried at Schweidnitz together with their father. In the photo Madame Niedermeyer places a flower on Manfred’s headstone.