. Kawasaki Ki-88 – data

Performance (specifications are estimations by Kawasaki)

Performance (specifications are estimations by Kawasaki)

Max speed at 19,685ft 600km/h 373mph

Range 1,198km 745 miles

Climb 6 min 30 sec to 5,000m (16,404ft)

Ceiling 11,000m 36,089ft

Armament

One 37mm Ho-203 cannon and two 20mm Ho-5 cannons

Deployment

None. The Ki-88 did not progress past a mock-up and partially completed prototype.

![]()

This story centres on the failure of a bomber that inspired the development of another new type. The Nakajima Ki-68 and the Kawanishi Ki-85, both four-engine, long – range bomber designs, hinged on the success of the UN’s Nakajima G5N Shinzan (Mountain Recess). The G5N would prove to be a failure and in turn led to the termination of the Ki-68 and Ki-85 programs; therefore the IJA was left without a long-range bomber project. It was Kawasaki who stepped in to fill the gap with their own design.

In 1938, the UN was enamoured with the idea of a bomber that was capable of operating up to 6,486km (4,030 miles) from its base. In part, this was due to the initial desire to strike targets deep in Russia from Manchurian bases. Later, when Japan went to war with the United States, a need to attack the US mainland was identified and it was recognised that a two-engine design would not suffice – four engines would be required. On the understanding that the Japanese aircraft industry had very little experience in building such aircraft, the UN used the Mitsui Trading Company as a cover to acquire a Douglas DC-4E four-engine airliner, ostensibly for use by Japan Air Lines. The development of the

DC-4E four-engine passenger aircraft was funded by five airlines and Douglas with United Airlines building and testing the one prototype. While the DC-4E was impressive, in terms of its operating costs it did not add up. The aircraft was complex and this resulted in maintenance issues, which increased the cost of using the plane. Support for the DC-4E was withdrawn and Douglas was asked to simplify the design. As a consequence, the DC-4 saw operational use with the US Army as the Douglas C-54 Skymaster.

In early 1939, the sale of the DC-4E was completed and arrived in Japan to be reassembled. By this time, the UN had informed Nakajima to be ready to study the DC-4E to produce a suitable bomber development from it. After having been flown several times, the DC-4E was then reported as having ‘gone down in Tokyo Bay’, but in reality had been handed over to Nakajima whose engineers took it apart. Within a year, Nakajima had built the prototype G5N1 which first flew on 10 April 1941. The G5N1 used only the landing gear layout, wing design and radial engine fittings from the DC-4E coupled to a new fuselage, tail design and a bomb bay. The IJA planned to produce the G5N1 and

Nakajima submitted the Ki-68 version using either the Mitsubishi Ha-101 or Nakajima Ha-103 engines in place of the Nakajima NK7A Mamom 11 units on the G5N1. Kawanishi also submitted their Ki-85 which was to use the Mitsubishi Ha-111M engines.

As it was, the G5N1 proved to be a dismal failure. The NK7A engines were problematic and underpowered and the aircraft was too heavy and complex. These difficulties contributed to the overall poor performance of the G5N1. Despite the problems, three more G5N1 aircraft were built followed by a further two aircraft that replaced the NK7A engines for four Mitsubishi Kasei 12 engines. The two additional aircraft were designated G5N2, but even the Kasei 12 engines could not resuscitate the design and the problems remained. Due to its complications, the G5N1 was never used as a bomber. Two G5N1 (using Kasei 12s) and two G5N2 aircraft were converted to transports and served in this role until the end of the war. The Allies gave the G5N the codename Liz.

By May 1943, the cancellation of the G5N had also brought the demise of both the Ki-68 and the Ki-85 (of which Kawanishi had a mock-up constructed by November 1942), leaving the IJA with no active four-engine

bomber designs on the table. Kawasaki, seeing the opportunity, immediately got to work on designing a new bomber. The man behind the Ki-91 was Takeo Doi, an engineer employed by Kawasaki. It was his goal to see the development of a successful four-engine

bomber and engineer Jun Kitano would work with Doi to help turn the aircraft into reality. In June 1943, Doi and Kitano began their initial research and by October, work on the first design concept for the Ki-91 was underway.

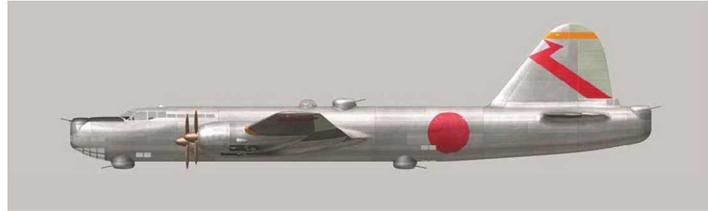

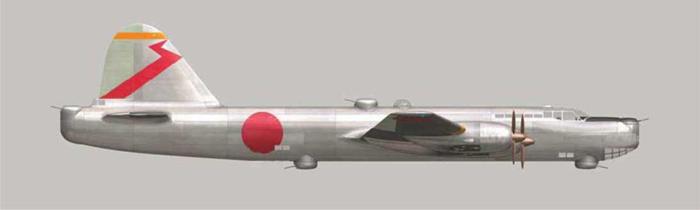

The Ki-91 was slightly larger than the Boe

ing B-29 Superfortress which was to be mass produced in late 1943. Four Mitsubishi Ha-214 18-cylinder radial engines were chosen to power the Ki-91. As the plane was expected to operate at high-altitude, provisions were made to utilise superchargers with the

engines and the projected maximum speed was 580km/h (360mph). To provide for the anticipated 10,001km (6,214 mile) range, each wing carried eight fuel tanks with a further two mounted in the fuselage above the bomb bay. For weapons, the Ki-91 was to carry a heavy armament of twelve 20mm cannons. Five power-operated turrets were to be used; one in the nose, one on the underside of the forward fuselage, one above and below the aft portion of the fuselage, and the last in the tail. The bottom turrets were remotely controlled while the remainder were manned. The tail turret was to mount four cannons while the rest had two cannons each. As far as bombs, a total payload of 4,000kg (8,8181b) was envisioned and the Ki-91 was to have a tricycle landing gear with the nose gear using a single tyre and the main landing gear using dual tyres. A semi – recessed tail wheel was also installed.

Another feature of the Ki-91 was to be the use of a pressure cabin for the eight man crew. But the development of such a large pressurised cabin for the Ki-91 was expected to take some time to implement, even using knowledge from another of Doi’s designs, the Kawasaki Ki-108, a twin-engine high-altitude fighter fitted with a pressure cabin for the pilot. Therefore, it was decided that the initial Ki-91 prototype would be built without pres-

surisation so as to avoid holding up development and allow its flight characteristics to be measured. Once the pressurised crew cabin for the Ki-91 was ready, subsequent aircraft were to have it installed.

In April 1944, a full-scale wooden mock-up was completed and Kawasaki invited IJA officials to come and review the Ki-91. Up until this time, the project was a private venture by Kawasaki to which considerable company resources has been allocated. If the IJA did not find the bomber to their liking, it would have been a waste of time, effort and money. Fortunately, the IJA saw potential in the Ki-91 and work continued. In May, the IJA inspected the Ki-91 mock-up and immediately ordered production of the first prototype. Kawasaki planned to construct the Ki-91 at a new plant in Miyakonojo in Miyazaki Prefecture. However, the IJA did not want to wait for the construction of a new plant and directed Kawasaki to use their established factory in Gifu Prefecture. By June 1944, the construction of the prototype Ki-91 had begun at the Gifu factory, together with the necessary tools and jigs to produce further aircraft.

However, June would see the first B-29 raids over Japan, but as the attacks were few and far between, work on the Ki-91 continued despite the worsening situation for the coun

try. This would change by the close of 1944 when B-29s began to operate from the Mariana Islands and by 1945 bombing raids were far more frequent. In February 1945, a raid heavily damaged the factory in which the Ki-91 prototype was being constructed. The damage was extensive, ruining the tools and jigs. With the loss of equipment needed for future production coupled with dwindling supplies of aluminium, the IJA decided that fighters to combat the marauding B-29s had become a higher priority than bombers. Any hope of utilising such bombers was at best slim. With the Ki-91 at 60 per cent completion, Kawasaki stopped further work on the bomber and the project was officially cancelled in February 1945.

Had the Ki-91 achieved service, plans to attack the US mainland were in place to operate the bomber from the Kurile Islands using temporary bases, while another plan to strike Hawaii was formulated using bases in the Marshall Islands. The second plan was rendered obsolete when the Japanese lost the Marshall Islands to the Allies in February 1944. As a note, contemporary images sometimes show the Ki-91 as having a bomb bay battery of downward firing cannons for a ground-attack role. While the Japanese were interested in such concepts, there is no evidence that Kawasaki envisioned such a task for the Ki-91.

![]()