THE COMBATANTS

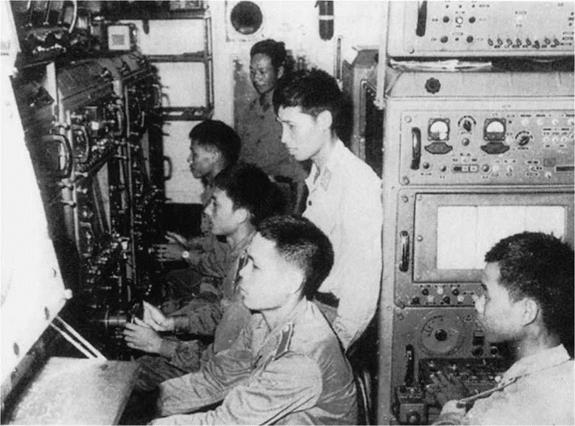

While the first North Vietnamese SAM troops were training in the USSR in 1965, Soviet PVO-Strany crews established and operated the country’s missile batteries. Having also formed ten training units around Hanoi, Soviet supervisors controlled the battalions for at least two years, causing some resentment among Vietnamese troops.

Battalions honed their skills on Firebee drones and later, at very much higher altitudes and unsuccessfully, on the A-12 and SR-71 reconnaissance aircraft that identified around 150 SA-2 sites soon after they began over-flights in November 1967. U-2 missions over North Vietnam were discontinued when the SA-2 regiments became operational.

North Vietnamese Dvina trainees in the USSR found difficulty with both the language and the heavy emphasis on ideology and inflexible discipline. Instructors insisted on the “three missile salvo” tactic — the first to make the target aircraft maneuver and thereby lose energy, making it an easier target for the second or third SA-2. Soviet advisors continued to refine their techniques throughout the war. For example, new anti-Shrike tactics included activating two “Fan Songs” briefly so that the missile would pass between them, while for the AGM-78, several “Fan Songs” were turned on and then simultaneously switched off, confusing the missile.

For Linebacker II, the nine SA-2 regiments and others recalled from the south were concentrated in Hanoi’s 361st Air Defense Division and around Haiphong. Their effort was directed in 1972 by Soviet Col-Gen Anotoliy Khyupenen. Faced with the B-52’s formidable jamming power, operators were told to use multiple launches at single targets so that the bombers’ EWOs, jamming each threat individually, were overwhelmed. Crews were also trained to launch SA-2s manually, only engaging “Fan Song” guidance in the final 15 to 20 seconds of the missile’s flight.

![]() Khyupenen conceded that, “The missile crews were inadequately trained to fight when jammed and under aerial attack. Fearing anti-radar missile strikes, the launch

Khyupenen conceded that, “The missile crews were inadequately trained to fight when jammed and under aerial attack. Fearing anti-radar missile strikes, the launch

SA-2 batteries usually worked in coordination with MiGs and AAA, but there were some inadvertent MiG casualties. Brig Gen Robin Olds, flying MiGCAP for an F-105 strike on the Canal des Rapides Bridge in August 19 67, saw a SAM hit a MiG-21 over Phuc Yen airfield. The strip antennas for the missile’s FR-15 Shmel radio proximity fuze can be seen on the nose of this SA-2 in its North Vietnam revetment. (via Dr Istvan Toperczer)

crews tried to fire at the B-52s without turning on their radars at all, which prevented them from detecting targets under jamming and switching to manual guidance”. He reported that only three B-52s were hit by missiles that had been actively guided — the norm was manual guidance, with automatic tracking for the last few seconds. In his estimation 64 SA-2s detonated too far from their targets, some on the metallic chaff used to mask the bomber formations. Most successful firings used at least two missiles. Several B-52s were hit as they made their post-bombing turn away from the target. As they banked, the intensity of their jamming was reduced, allowing canny “Fan Song” operators a rapid lock-on.

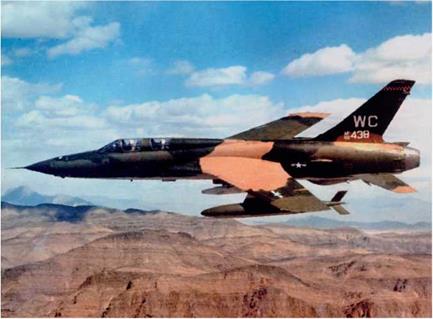

![]() F-105Gs were vulnerable too. The last Weasel loss (63-8359) of the war, on November 16, 1972, was escorting B-52s near Thanh Hoa when a SAM site fired. Maj

F-105Gs were vulnerable too. The last Weasel loss (63-8359) of the war, on November 16, 1972, was escorting B-52s near Thanh Hoa when a SAM site fired. Maj

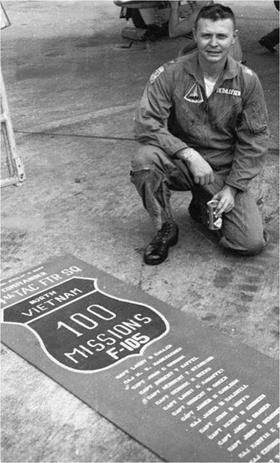

LEO K. THORSNESS

Like fellow Wild Weasel Medal of Honor winner Merle Dethlefsen, Leo Thorsness was born a Mid-West “farm – boy” in the early 1930s and chose to fly fighters after receiving his pilot’s wings. Both men flew the F-100 Super Sabre before transitioning to the F-105 and being posted to Takhli RTAFB in 1966. As Col Jack Broughton, Vice Wing Commander of the 355th TFW told the author, “At Takhli I had a super-smart, aggressive good guy Weasel leader in Leo Thorsness. We were almost always short on Weasel aircraft and crews. I wanted one Weasel guy to manage the assets and call the shots”.

Thorsness arrived at Takhli in the second batch of Weasel crews soon after the first five F-105Fs had been lost in just 45 days in July-August 1966. He was determined to try new tactics, which included flying the Weasel missions at higher altitudes – around 18,00020,000ft – in order to reduce the loss rate. With his regular “Bear”, ex-B-52 EWO Capt Harold E. Johnson, Thorsness also pioneered the idea of splitting the Weasel flight into two elements, with an F-105F and an F-105D in each pair, as a way of doubling the potential SAM-site attacks.

On April 19, 1967, Thorsness and Johnson, in F-105F 63-8301, were lead “Kingfish” Weasels for an attack on the Xuan Mai barracks near Hanoi. The second “Kingfish” element was jumped by MiG-17s, and Majs Thomas Madison and Thomas Sterling were forced to eject from F-105F 63-8341 – Dethlefsen’s Medal of Honor mission aircraft. “Kingfish 1” completed its bomb-run and set off to cover the Weasel crew as they parachuted down. Both “Kingfish” F-105Ds were also damaged and had to withdraw, leaving Thorsness’s F-105F as the only

American aircraft in the area. Noticing a MiG-17 that was about to make a strafing run on Madison and Sterling,

Maj Thorsness shot it down and then out-ran a second MiG-17.

Low on fuel, he headed for a tanker, called in a RESCAP team for the downed Weasels and briefed them on the situation, and on SAM evasion tactics as they were dangerously near Hanoi. After a brief discussion with his “Bear”, Thorsness then returned to provide solo cover for his wingman. En route they encountered a “wagon wheel” formation of five MiG-17s, and Thorsness fired out his last 500 rounds at one, scoring a probable kill. The other four immediately pursued him, and he dived in afterburner to weave through several valleys, sometimes flying below 50ft as he shook off the VPAF fighters.

Meanwhile, another MiG-17 flight had shot down the lead RESCAP A-1E “Sandy” aircraft (flown by Maj John Hamilton) and Thorsness returned to the fight once again, advising Hamilton’s wingman to turn hard just above the forest to evade the MiGs. Although out of ammunition, the F-105F crew turned hard into the MiG-17s, denying them a target and allowing “Sandy 02” to escape. Low-altitude maneuvers in afterburner had run the F-105F low on fuel again and Thorsness sought another tanker, feeling that the rescue had failed since contact with the downed crew was impossible.

In his brief absence the “Brigham Control” rescue coordinator had directed “Panda” (a post-strike F-105 flight) into the rescue area, where its leader, Capt William Eskew, had shot down a MiG-17 – two other VPAF fighters had also been seriously damaged. A third F-105 strike

Peter Giroux in the B-52 cell saw the first missile just miss the leading bomber, but “a second or two later I saw a second SAM light up the overcast almost directly below the F-105. It popped through the clouds and almost immediately struck the underside of the ‘Thud’. The ejection seats went out seconds later, and I was surprised that I could see them fire at this distance”. Maj Norbert Maier and Capt Kenneth Theate ejected and were recovered after a hair-raising duel between rescue forces and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) troops.

In 1966—68 the Weasels’ primary weapon was the Shrike, and with Soviet guidance 44 the SA-2 operators learned to defeat it. Their primary defense was simply to turn off

persuaded a tanker pilot to come north and meet up with Bodenhammer, rather than see him eject. A quick calculation convinced the Weasel crew that they could just get to Udorn RTAFB, and they effectively glided the F-105F for 70 miles, landing with a zero reading on the fuel gauge. For a mission that Harry Johnson described as “a full day’s work”, Maj Thorsness was later awarded the Medal of Honor and Capt Johnson the Air Force Cross.

Eleven days later, on the 93rd mission for Maj Thorsness and his second that day, things went very wrong for his “Carbine” flight. With communications drowned out by a malfunctioning emergency beeper in an F-105’s ejection seat, his element was jumped from below by a 921st Fighter Regiment MiG-21 flight led by VPAF ace Nguyen Van Coc. Thorsness’ wingman, 1Lt Robert Abbott, was shot down in F-105D 59-1726 and Thorsness’ F-105F (62-4447) took an “Atoll” missile, fired by Le Trong Huyen, in its tailpipe. Badly injured in an ejection at almost 600 knots, and filled with a sense of failure, Thorsness landed hard with a damaged parachute. He and Johnson were soon captured. Thus began an agonizing, but heroic, six – year prison sentence in Hanoi.

Finally released in March 1973, Thorsness received his Medal of Honor from President Richard Nixon on October 15, 1973 – his receipt of this award was kept secret while he was a PoW as there were concerns that the North

flight ("Nitro”) was vectored in to provide further cover, Vietnamese would use this against him. Unable to return

and Majs Jack Hunt and Ted Tolman each shot down a MiG. to fighters because of the back injuries he suffered in his

However, “Panda 03” (Capt Howard Bodenhammer) ejection, Thorsness retired from the USAF with the rank of became separated in the dogfight and had only 600lbs of colonel. He subsequently served as director of civic fuel remaining. Despite his own fuel shortage Thorsness affairs for Litton Industries, prior to taking full retirement.

the “Fan Song”, denying the Shrike its target. Missile crews also realised that they could track incoming Weasels on radar, watching for one to pull up into a climb to “loft” a Shrike at them and then turn off the radar. They realised too that the Shrike’s exhaust gases contained tiny metal fragments from its solid rocket fuel. These gave a strong enough radar trace to provide warning of an incoming missile. Combined with the “dummy load” power switch described earlier, these techniques severely reduced the Shrike’s chances of a kill, particularly from long range. They also frustrated dummy attacks on sites by Weasel crews who were attempting to force the

radar off the air through the threat of a Shrike launch. 45

It was also clear that multiple Shrike launches did not improve the missile’s success rate either. However, as a 1973 USAF Security Report concluded, “By their very presence, these aircraft reduced SAM firing rates considerably, and sometimes by as much as 90 per cent”. Col James McCarthy, leading a wave of Linebacker IIB-52s, reported “About ten seconds prior to bombs away we observed a Shrike being fired, low and forward of our nose. Five seconds later several SAM signals dropped off the air and the EW (ECM operator) reported they were no longer a threat to our aircraft”. By Night 4 of the campaign, most SA-2s were manually guided, sometimes with range information from I-band signals from “Fire Can” radars, and most missiles were fired at bombers within ten miles of the sites, at two – to three-second intervals. New consignments of ARMs were tuned to operate in I-band.

Training for the early Wild Weasel crews was minimal. Capt Ed Sandelius was the only TAC EWO in the pioneering 469th TFS at first:

SAC had about 85 per cent of the EWOs and electronic warfare equipment. We were all trained EWOs, so the receivers were a piece of cake. The AN/APR-25/26 provided relative bearing. With practice you could interpret relative signal amplitude and get quite

good at estimating range. When you flew over a site, the signal’s amplitude would get extremely long and switch from 360 to 180 degrees. At this time you would try to pick up the site visually.

WildWeasell pilot Capt Allen Lamb added:

There was no training to speak of for Wild Weasel I. We did run against the SADS-1 “Fan Song” simulator at Eglin AFB to check the accuracy of the equipment. Then we went to war to see if it would really work.

The length of the strobe indication on the RWR scope showed how close the “Fan Song” was. If it reached the first or second concentric ring there was little immediate danger, but a “three ringer”, reaching the outer ring, represented a real threat.

The learning curve was still rising when Dan Barry began F-105F/G missions in 1970:

On my first tour at Takhli with the 44th TFS we had a “combat tips book” full of various combat lessons learned by “Thud” pilots ahead of us. One had to do with evading a SAM at night, and the author had written, “Imagine yourself in a huge parking lot in the dark of night and a motorcycle is coming at you at maximum speed. Because there is only a single headlight you have no gauge for distance or closure rate to know when to jump out of the way. You just have to guts it out because if you move too soon he corrects and nails you. If you jump too late he’s tracked you all the way to the kill. You only have one chance and you have to do it right”.

In Capt Terry Gelonick’s experience, “Even though they zigzagged on their upward flight, we had been briefed that if a SAM was tracking our aircraft it would maintain its same relative position on the cockpit window”.

Wild Weasel crews had to face a multitude of threats, including MiGs that were usually coordinated with AAA and SA-2s. Of the 23 F-105s shot down by VPAF pilots, with the loss of ten USAF aircrew, six were Iron Hand or Weasel two-seaters. Only one was an F-105G, lost on May 11, 1972 during an Iron Hand mission near Hanoi. Two SA-2 batteries were ordered to fire six missiles at the flight as it moved in on a third site. While the F-105G crew (Majs Bill Talley and Jim Padgett) were fully occupied in defeating the SAMs, they did not see a MiG-21 flight closing in behind them. Their aircraft, 62-4424 Tyler Rose of the 17th Wild Weasel Squadron (WWS), was hit by an “Atoll” missile from Ngo Duy Thu’s MiG-21.

Maj Talley, on his 183rd mission and third combat tour, had made an emergency landing at Da Nang after a compressor fire ten days previously and thought that he had another failed turbine. He slowed to 350 knots and ejected with Padgett (on his 13th mission) at 1,000ft. “I landed on the side of a mountain and climbed to the top to await rescue”, Talley explained. “However, the rescue attempt was not made until mid-morning of the following day. I was captured just as the rescuers flew into the area where I was hiding. They tried to rescue my back-seater but were driven away by MiGs”.

|

|

Engine failure was another occupational hazard for Thunderchief crews as their J75s struggled with frequent over-work. Engine fires were common. Indeed, 31 aircraft — half of the wartime non-combat casualties — were lost to engine or oil system problems, including eight Weasels. Fortunately, all were over Thai territory, although five pilots died in these accidents. Above all, Weasel crews learned to cope with the unexpected.

For example, after knocking out several “Fan Songs” on July 29, 1972, an Iron Hand flight on its way home was caught by a MiG-21. As they turned to avoid its “Atoll” missile, Majs T. J. Coady and H. F. Murphy jettisoned their centerline tank, which wrapped itself around the F-105G’s wing, shorted wires in the AGM-78 pylon and fired the missile towards US Navy ships off-shore! As the vessels closed down their radars, the F-105G (62-4443) refueled in afterburner and headed for Da Nang. Sadly, the errant tank prevented the main landing gear from extending and the crew had to eject.

The complexity and physical duress of the F-105G’s cockpit in the days before automation could also be daunting. Dan Barry recalled:

|

In the summer of 1972 I was flying a night B-52 support mission at the western end of the DMZ with my “Bear”, John Forrester. Just about the B-52s’ time-on-target, without any RHAW signals, three SAMs started coming off the launchers about ten miles in front of us. In the blackness I immediately picked them up visually and we simultaneously started receiving their guidance signals. John started calling, “Give me the big one!” I had a Shrike selected since I usually preferred to monitor its audio signal, so I had to start switching to the AGM-78 instead while maneuvering to get the SAMs out at “two o’clock” and pushing the nose down to get our Mach up for evasive maneuvering.

NGUYEN XUAN DAI AND PHAM TRUONG HUY

Officially recognized by the NVA as a hero following his service with the 61st Battalion, 236th Missile Regiment, Nguyen Xuan Dai operated the range tracking controls of a “Fan Song” at Hai Duong, Ha Noi and Ninh Binh.

The soldiers on his course were ready to start missile training as early as May 11, 1965, but they had to curtail their tuition on the SA-2 after only two months, rather than completing the normal nine-month course, because of increased US air attacks. The NVA crews effectively learned to operate the SAM systems in practice “on the job”, studying the technical aspects of the equipment at a later date. On their first day in action – July 24, 1965 – Nguyen Xuan Dai’s team shot down F-4C Phantom II 63-7599 of the 15th TFW (the first American SA-2 casualty), and later also claimed to have destroyed the 400th US aircraft credited to North Vietnam’s militia.

After each SA-2 engagement, Nguyen Xuan Dai and his team would quickly take cover under nearby trees just in case their battery had been targeted by an ARM. Once the all clear had been given, they would move with the battalion to another site. The SM-63 launchers themselves would only be moved under the cover of darkness, a tractor being used to pull the 12-wheeled vehicle. Travel time depended on the distance to the next site. For example, it took soldiers two days to move the missiles from Ninh Binh to Ha Tay.

Like other types of missile, when the SA-2 was activated the first stage of the rocket propellant created a huge cloud of dust and smoke and a large explosion to thrust the missile into the sky.

Personnel manning the SA-2 sites were always prepared for action. Fortifications for the weapons were dug deep into the ground, and the transporters, computing van and other vehicles, including the radar vans, were hidden. Initially, the Soviet SAMs were supplied in an overall white finish, but during the war they were resprayed in dark green paint and camouflaged with leaves that matched the battlefield terrain. Personnel even planted trees around the more permanent fortifications to deceive the USAF

Each launcher had five to six people on duty as loaders, while the “Fan Song” team had three troops – one operator to monitor target altitude, another tracking the position and a third monitoring range. A control officer observed when the target was first detected and then turned the “Fan Song” antenna to locate the target.

Soldiers like Nguyen Xuan Dai always felt nervous before combat, but they never thought about matters of life and death. They just tried to hit the targets, although the SA-2’s most effective interception method was impeded by US jamming. American aircraft, particularly the B-52, had 15 different types of jammer they could employ, while the EW-dedicated EB-66 also restricted the capability of the SA-2. Moreover, the Americans understood how the SA-2, and its radar, worked, so many early sites were heavily damaged.

Nevertheless, the NVA was quick to find new and creative ways to attack US aircraft, using manual tracking and the three-point method. Nguyen Xuan Dai recalled that after one particular engagement his regiment hid their weapons and erected fake missiles made of bamboo framework that had been painted green to resemble a real SA-2. These attracted US aircraft and enabled the AAA units around the site to find targets easily. Five American fighters were duly shot down by AAA while attacking these fake sites.

Meanwhile, I tried to get the ’78 to fire, with no luck. In the blackness I immediately picked them up visually and we simultaneously started receiving their guidance signals. John started calling, “Give me the big one!” While the first two SAMs went well below us, the third looked like it had our names on it, and for the only time in two Weasel tours I told John to turn on the jammers. As the missile zeroed in on us I remember gritting my teeth ’til I couldn’t stand it anymore, and then pulling all the gs I had speed for and rolling into it because I knew the SAM fragmentation pattern exploded in a forward-oriented cone. I was sure it was so close it was going to detonate. When it roared past us the rocket

Pham Truong Huy recalled that in late March 1972 his 62nd Battalion moved to Quang Tri during the Spring Invasion, and it was credited with the first shoot-downs of that campaign – EB-66C 54-0466 “Bat 21” on April 2 and OV-10A 68-3820 five days later. In fact, the People’s Army of Vietnam newspaper for April 5, 1972 described how an “intensely burning B-52 had fallen, broken pieces of it falling to the ground”. The EB-66 pilot, Lt Col Iceal Hambleton, was recovered after one of the most extensive and costly SAR efforts of the Vietnam War, but the jet’s remaining five crewmembers were killed when the EB-66 crashed near Quang Tri. Pham Truong Huy recounted with pride that he had controlled the missiles that claimed three aircraft from the same battery, which few soldiers could do well. Aside from the EB-66 and OV-10, Pham Truong Huy’s battery also claimed a B-52 in the Cam Lo-Quang Tri area.

Due to the topography of the hilly areas near the demilitarized zone (DMZ), batteries could only deploy three missile launchers rather than six, and they had to be set up on land that was both partly soft and partly hard as there was insufficient time to build a firmer base. This in turn meant that when missiles were fired the launchers were unstable, leaving them damaged. With no spares available, crews had to effect running repairs on the launchers as best they could.

Although they enjoyed considerable success in 1972, missile crews also suffered painful losses when the USAF attacked their sites. One night in September 1972 Pham Truong Huy was just minutes away from intercepting a B-52 when USAF fighters located his site. Kham, one of his comrades, died in the heavy attack that followed, being struck in the head with shrapnel before he had time to

don his steel helmet. He died at his position at the “Fan Song” command computer.

A missile soldier lived and fought with his unit for a long time. Indeed, they could be separated from their families for up to seven years. They had to be very resilient and endure hardships, particularly when they moved south “into the field” in 1972. They ate on the site and often had to source water from local villages, travelling up to two kilometers just to bathe.

Ultimately, the efforts of the SA-2 batteries were duly recognized on Reunification Day (April 30, 1975), when the missile soldiers were present in force at the victory parade held in Hanoi.

SA-2 Air Defense veteran Nguyen Hong Mai (left), Professor Pham Cao Thang, USAF F-4 Phantom II ace Brig Gen Steve Ritchie and Nguyen Vinh Tuyen view We and MiG-17, a study of North Vietnam’s air defenses by Vietnamese author Thuy Huong Duong (second from right). No photos exist of Nguyen Xuan Dai or Pham Truong Huy.

(Thuy Huong Duong)

motor lit up the cockpit and the shockwave gave us such a severe jolt I thought we’d been hit. Fortunately, it had gone under us and exploded 10,000 ft above us at 20,000 ft.

As we headed back to the tanker we tried to figure out what saved us. I couldn’t confirm whether I made the correct switch selections to get the AGM-78 launched, and in hindsight I should have pickled a Shrike and then changed weapon selection.

We wondered if the jammer had “blossomed” the SAM radar at just the right point to confuse them, or maybe they had bad fuzing. All this happened in less than 15

seconds, and I’ve always felt fortunate I didn’t have to rethink it in a cell in Hanoi. 51