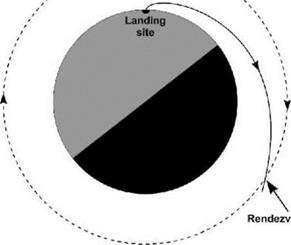

Direct ascent

The obvious way to rendezvous was to launch off the Moon on a trajectory that directly intercepted the CSM using a single burn of the ascent engine. This was discarded for many reasons. The timing of the launch would have had to have been extremely accurate for the LM to intercept a spacecraft passing by at 1.6 kilometres per second. Even with such split-second accuracy, engineers knew’ that the expected variations in the thrust from the ascent engine would cause the EM to miss the CSM by gross margins. Additionally, the short duration of the approach gave little time to

|

CSM orbit, -‘

Diagram of the direct ascent technique. |

calculate and correct the trajectory. Furthermore, the closing speed would have been higher than the RCS thrusters could be expected to overcome and if the approach was missed, the LM would find itself in an orbit whose perilune was likely to be below the lunar surface – that is, it would climb, arc back and crash onto the Moon. Direct ascent rendezvous was dangerous in many ways, and on top of all that it would be very difficult for the CSM to rescue a stricken LM.

fn addressing these problems, engineers settled on a more elaborate technique that took a step-by-step approach to incrementally bring the LM towards the CSM in a manner that could be analysed and controlled.