The panoramic camera

The more powerful of the two cameras in the SIM bay was the panoramic camera, which was also derived from contemporary secret reconnaissance cameras. Far from conventional, this large camera produced enormous negatives 114 mm wide and 1.15 metres long. An exposure was made by rotating a large lens of 610-millimetre focal length from one side to the other while simultaneously winding film through the camera. The long axis of the resultant image was perpendicular to the spacecraft’s orbital track and documented a swathe of terrain 330 kilometres from end to end.

The imagery at the centre of the frame showed the ground directly beneath the spacecraft and could resolve features as small as two metres across. Included with the camera was a sensor that measured how rapidly the ground was moving past the camera in order to compensate for motion smear during the exposure. Additionally, the entire optical assembly could be pivoted forwards and backwards to facilitate stereo imaging of the same landscape with every fifth exposure. This huge camera was fed by a cassette that held two kilometres of film, sufficient for over 1,500 exposures during a mission.

Once the spacecraft had begun its long coast back to Earth, the CMP made a brief spacewalk down the side of the service module to retrieve the cassettes for both the panoramic and the mapping cameras.

Once the spacecraft had begun its long coast back to Earth, the CMP made a brief spacewalk down the side of the service module to retrieve the cassettes for both the panoramic and the mapping cameras.

Remote sensing

Lunar scientists took the opportunity, and the flowing money associated with Apollo, to endow the SIM bay with other capabilities in addition to its photographic coverage. These allowed measurements of the Moon’s composition to be taken across a wide area from orbit. These could be calibrated and contextualised by the ‘ground truth’ provided by the surface crews.

Techniques for determining the composition of distant astronomical bodies were worked out by astronomers in previous centuries. In simple terms, they relied on the property of substances to radiate or absorb light in precise wavelengths, or energies. To the eye, each substance appears to have a characteristic colour which, when spread out into a spectrum by a spectrograph, reveals patterns of lines that act as a fingerprint of that substance. Spectra for common chemicals can be obtained in a laboratory. When the same patterns are observed in the light from distant bodies, researchers can be certain of the chemical constituents in that body. All you need is a spectrograph to break light into its separate colours and you can see the patterns of radiation or absorption that correspond to each substance.

Using appropriate instruments, this basic technique can be expanded beyond the narrow range of light wavelengths that we see with our eyes to include the wider electromagnetic spectrum and the various particles associated with ionising radiation. As the CSM flew over the Moon, instruments in the SIM bay took

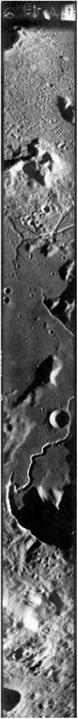

A frame from Apollo 15’s panoramic camera showing Hadley Rille.

" (NASA)

advantage of the complete lack of a worthwhile atmosphere to determine the makeup of the surface using a varied suite of techniques.