On the road

For the first traverse with a rover on the Moon, Scott and Irwin headed southwest towards a spot where Hadley Rille took a sharp turn below the flank of Mount Hadley Delta. "Well, I can see I’m going to have to keep my eye on the road,” commented Scott as he negotiated the undulating terrain of the plain. "Boy, it’s really rolling hills, Joe. Just like [Apollo] 14. Up and down we go.”

The chaotic nature of the landscape kept him busy as he worked the rear-wheel steering to avoid fresh, steep-walled craters and occasional rocks large enough to be hazards.

"We’re going to have to do some fancy manoeuvring here,” remarked Scott. "Okay, Joe, the rover handles quite well. We’re moving at an average of about eight kilometres an hour. It’s got very low damping compared to the one-g rover, but the stability is about the same. It negotiates small craters quite well, although there’s a lot of roll. It feels like we need the seat belts, doesn’t it, Jim?”

“Yeah, really do,” agreed his LMP.

“The steering is quite responsive even with only the rear steering,” continued Scott. “I can manoeuvre pretty well with the thing. If I need to make a turn sharply, why, it responds quite well. There’s no accumulation of dirt in the wire wheels.”

“Just like in the owner’s manual, Dave,” said Allen.

The speed that Scott could maintain was typical for the rover and though it may not appear to be very fast, the combination of the heavily cratered surface and the light lunar gravity made the vehicle pitch and roll enough to take the wheels off the ground. “Man, this is really a rocking-rolling ride, isn’t it?” laughed Scott.

Irwin concurred. “Never been on a ride like this before.”

“Boy, oh, boy! I’m glad they’ve got this great suspension system on this thing.”

Young and Duke’s first traverse took them west for a short distance away from the LM. “Man, this is the only way to go, riding this rover,” said Duke.

But a disadvantage of driving west was that the Sun was behind them and so there were few shadows in front of Young to help him judge the terrain ahead. Essentially, all objects directly ahead were hiding their own shadows. Worse, at the point directly opposite the Sun, the so-called zero-phase point, the backscattered reflection from the tiny crystals in the regolith became particularly bright to the point of being dazzling. It limited their speed as Young fought to discern the obstacles ahead in the glare.

“Driving down-Sun in zero phase is murder,” moaned Young. “It’s really bad.” He elaborated further during his post-flight debrief. “Man, I’ll tell you, that is really

|

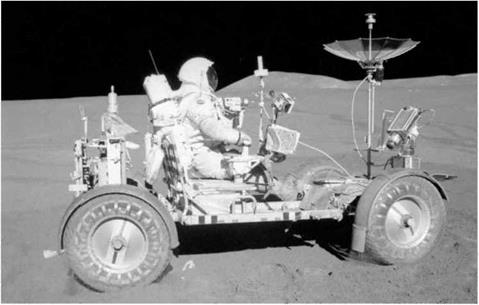

David Scott driving Lunar Rover-1. (NASA) |

grim. I was scared to go more than four or five kilometres an hour. Going out there, looking dead ahead. I couldn’t see the craters. I could see the blocks alright and avoid them. But I couldn’t see craters. I couldn’t see benches. I was scared to go more than four or five clicks. Maybe some times I got up to six or seven, but I ran through a couple of craters because I flat missed [seeing] them until I was on top of them.”

The speed record for driving a rover probably goes to Gene Cernan on his second lunar EVA when he and Schmitt were driving down a scarp that crossed their valley floor. On the Moon, slopes tend to be smoother than level ground because the gradient tends to make particles move preferentially downhill with every micrometeoroid hit and the constant downslope movement smooths out the features. "What was it. 17’A or 18 clicks we hit coming down the Scarp. Jack?" claimed Cernan nonchalantly. Schmitt merely laughed at the suggestion.

Л record that Apollo 17 s rover can claim is to have taken its crew furthest from the LM. On EVA 2’s outbound leg. Cernan drove 9.1 kilometres to a site at the foot of the South Massif, fully 7.4 kilometres distant from Challenger, its safety and a ticket home to Earth.

John Young took his rover to its own record – the highest point up a hillside reached by any crew at 170 metres. The rover’s easy glide up Stone Mountain was in stark contrast to the labour-intensive struggle Shepard and Mitchell had climbing 85 metres up a much shallower slope in an effort to reach Cone Crater. At the Cincos craters. Young came to a stop and looked around to see the view. Duke was the first to speak up and tell Tony England about it. "Tony, you can’t believe it, this view looking back. We can see the old lunar module! Look at that, John.” But Young was too busy getting the rover parked in a position where it would not begin to slide back downhill. He had the experience of Apollo 15 to draw from.

On their second traverse. Scott and Irw’in had taken their rover onto the lower slopes of Mount Hadley Delta. Among their goals, they wanted to find anorthosite, a white crystalline rock that geologists believed would be a sample of the Moon’s primordial crust. The mountain was thought to be a block of that crust and the hope was that by driving a short distance up the hill, they would find a sample that had been dislodged from further up. Scott generally tried to park inside the lower rim of a crater as this tended to be a relatively level spot on the otherwise sloping ground. However, at one point, he was attracted to a boulder in which Irwin had spotted a hint of green in its dusty surface. On giving up on one parking spot above the boulder because the slope was too steep, Scott found that as he went to dismount at a spot below the boulder, he could feel the vehicle slide. In fact, the rover was sitting with one of its wheels off the ground. To keep it in place, he had to ask Irwin to stand below it and hold onto it while he investigated and sampled the green boulder.