THE LON KEY WORLD OK THE CMP

With the departure of his two erewmates to the lunar surface, the CMP had a bigger space in which to move around so life on board the Apollo command module became somewhat more comfortable. Michael Collins elaborated on this extra space in his autobiography.

‘T have removed the centre couch and stored it underneath the left one, and this gives the place an entirely different aspect. It opens up a central aisle between the main instrument panel and the lower equipment bay. a pathway which allows me to zip from upper hatch window to lower sextant and return.” One reason that Collins created this extra room in the cabin was in ease his erewmates returned and found they could not get through the tunnel for whatever reason. All three men would be in their space suits and the two surface explorers would enter through the main hatch, clutching boxes full of rocks. Collins appreciated the extra room now afforded him: "In addition to providing more room, these preparations give me the feeling of being a proprietor of a small resort hotel, about to receive the onrush of skiers coming in out of the cold. Everything is prepared for them; it is a happy place, and I couldn’t make them more welcome unless I had a fireplace.”

Collins had a relatively short time alone in the command module, and much of it was spent on housekeeping duties or looking through the sextant in vain to find his colleagues on the surface. He also found that there was very little time available to speak with mission control. Only one communication channel was available between the Moon and Earth through a single Capcom and this was being dominated by the large amount of chit-chat from the guys on the surface as they talked to mission control and to each other. This became somewhat problematic as the needs of the orbiting CSM and its sole occupant vied for Lime on a link that was already busy with the important task of keeping two men alive and working on the surface of an airless world.

Richard Gordon on Apollo 12 had a similar experience, except that he had no problem finding the LM. given Pete Conrad’s pinpoint landing. Towards the end of Gordon’s Lime alone in the CSM, he did get to push the science possibilities of the orbiting spacecraft a little when he operated a cluster of four Hasselblad film cameras mounted on a ring, each loaded with black-and-white film and each shooting through a different filter. This cluster was attached to the hatch window and allowed him to photograph the surface in red, green, blue and infrared light. The idea was to detect subtle hue variations across the surface that would relate to the composition of the soil. Telescopic studies had shown that some mare surfaces had a slight reddish tinge while others were bluish. A similar experiment had been attempted on Apollo 8 when Bill Anders photographed the maria through red and blue filters. However, excessively fatigued. Anders had inadvertently installed a magazine of colour film on the camera instead of the black-and-white magazine required by the experiment.

After Apollo 12. NASA decided that the increasing complexity of the missions required there to be two Capcoms, one for each spacecraft. This was readily achieved since the MOCR was already partially divided between the LM and CSM monitoring functions and there were separate consoles for the LM systems (Control, who looked after the LM’s guidance systems and engines, and TELCOM, later TELMIJ. who oversaw its electrical and environmental systems, much as НЕСОМ did for the CSM).

As their crewmates laboured on the surface dealing with suits and geology in the Moon’s dust pit, the CMPs handled an incessant programme of data collection and observation, while they simultaneously cared for the spacecraft. In addition to their planned tasks, it was not unusual for the CMP to deal with requests from geologists for yet another observation, or for a flight controller to seek clarification of a nuance of the CSM’s operation. This could create a steady chatter over the airwaves during each pass across the near side.

“It turned out that my favourite experiment in orbital science was the bistatic radar," said Ken Mattingly after his Apollo 16 flight. T his experiment used the spacecraft’s communication antenna to beam radio energy at the Moon as the spacecraft passed across the near side while radio telescopes on Earth received the echoes. To work, the signal from the antenna transmitted only a carrier wave and therefore could not carry information. “That meant the ground couldn’t talk to me for an hour and a half. I had a chance then to go to the bathroom, eat dinner, and get an exercise period or look at the flight plan. I think you really need those kind of periods every now and then throughout the day.”

Occasionally the CMPs got Lime to enjoy the view and the experience of coasting across the Moon alone. Owing to the easterly position of the Apollo 17 landing site, most of the near side track was in lunar night, but it was a night time lit by an Earth that was much larger and far brighter than the Moon appears to us. “Boy.“ reported Ron Evans, “you talk about night flying, this is the kind of night flying you want to do, by the full’ Earth.”

“Is that right?” said Mattingly, now’ in the Capcom role in the MOCR.

“Beautiful out there,” said Evans as he watched the ancient landscape of the Moon drift by, illuminated by the soft blue-white glow of his home planet.

As America coasted over to the western limb, Mattingly warned that when Evans eamc back around he would read up a lengthy scries of updates to the flight plan to satisfy the geologists’ desire for further photographic coverage. lie then asked for a stir of the spacecraft’s hydrogen tanks. It was December 1972. midwinter on Earth’s northern hemisphere.

"You’re lucky you’re up there tonight. Ron. We’re having really ratty weather down here. Low clouds and rain and drizzle and cold.” said Mattingly.

"Oh, really?" replied Evans as he approached the edge of Mare Orientale. a spectacular impact basin barely visible from Earth and unrecognised until the 1960s.

"Yes. You walk outside, you just about can’t see the top of building 2.”

"Gee whiz! Guess I picked a good time to be gone.” said Evans.

“Thai’s for sure.”

Evans was enjoying the view when he spotted a flash on the surface, probably a meteor strike. "Hey! You know, you’ll never believe it. I’m right over the edge of Orientale. I just looked down and saw a light-flash myself.” Jack Schmitt had seen a similar flash just after they had entered lunar orbit.

"Roger. Understand,” replied Mattingly.

"Right at the end of the rille that’s on the east of Orientale.”

On Apollo 15. A1 Worden figured that since he was going to be reappearing from around the Moon’s far side every two hours, it would be a fitting gesture to greet the planet in a variety of languages to make explicit that he was greeting the whole Earth and its inhabitants, not just its English speakers. With help from his geology teacher. Farouk El-Baz, he wrote down the words, "Hello Earth. Greetings from Endeavour." phonetically in a selection of longues. Then, as he re-established communication with Earth, assuming that the pressure of work had relented enough, he would choose one of these languages as his way of greeting the world.

Worden found his time alone in the CSM to be busy but not unpleasant. When asked about how hard mission control would drive him after his rest break, he said, "It was not generally difficult to begin work in the morning, because I was usually awake by the time they called. Also. I spent roughly half [of my] time on the back side of the Moon, and so 1 had about an hour each revolution when 1 could not talk to Houston in any event. I was up and going before talking to Houston because I did not sleep that much during the orbital phase."

Another time, he recalled, "My impression of the operations of the spacecraft was one of complete confidence in the equipment on board. Things worked very smoothly, and 1 didn’t have to keep an eye on all the gauges all the Lime. The rest of the spacecraft ran just beautifully the whole time. The fuel cells ran without a problem. In fact, everything ran just beautifully, and I really had no concern for the operation of the spacecraft during the lunar orbit operations.”

Just being human

Everyone involved in Apollo’s exploration of the Moon was acutely aware that time on the lunar surface, or in lunar orbit for that matter. w:as gained at extraordinary expense, was extremely precious and had to be carefully rationed to gain maximum scientific return. Nonetheless, the human dimension, the sense of the occasion or our innate tendency to lighten things up a bit often managed to shine through. Every crew left objects behind, perhaps for future visitors to find or maybe just in the knowledge that something meaningful had been left behind on that extraordinary world. Like Worden’s greetings, Evans’ joy at flying in Earthlight or an impromptu ballet display that Jack Schmitt indulged in on the lunar surface, there would be moments of humanity that w ould turn these periods of relentless data gathering into something to which a wider audience could relate.

As would be expected, Apollo 1 l’s brief EVA was crammed with activity. Armstrong and Aldrin had to hustle to get everything done but time was set aside for a conversation between the crew and President Richard Nixon who spoke from the While House. Then, after they had conveyed their gear and samples up to the LM, Armstrong remembered one other item. “How about that package out of your sleeve? Get that?” He was still on the surface and Aldrin was in the cabin receiving the gear.

“No.”

“Okay, I’ll get it when I gel up there.”

“Want it now?” asked Aldrin.

“Guess so.”

Aldrin removed the package from one of his sleeve pockets and tossed it down to the surface where Armstrong positioned it with his foot.

“Okay?”

“Okay,” replied Aldrin, both men happy with its placement. The pouch contained patches and medals to honour space travellers – Russian and American alike – who had died, a gold olive branch to represent Apollo ll’s peaceful goals and a small silicon disk etched with messages from world leaders.

The seriousness of Apollo 11 gave way to the exuberant fun of Conrad and Bean just four months later. Their big idea was to smuggle a timer on board that would have operated their Hassclblad camera with a time delay. This would have allowed both crewmen to pose in front of the Surveyor 3 probe. They took great care to ensure the timer got to the Moon but when it came time for their surreptitious photograph, they could not locate it in the bag where it lay. By this lime, the bag was full of rocks and copious quantities of the tenacious dust that covered everything. Later, as they dumped the contents of the bag into a rock box next to the LM. the timer appeared. “That was when we should have done it,” recalled Bean years later. "We’d have had the LM in the background. We could have shook hands in front of the LM. It’d be the end of the HVAs. Been a great picture.”

On Apollo 14. A1 Shepard’s passion for golf inspired his stunt. Facing the TV camera at the end of his final EVA, he launched into his demonstration. “You might recognize what I have in my hand as the handle for the contingency sample return; it just so happens to have a genuine six iron on the bottom of it. In my left hand. I have a little while pellet that’s familiar to millions of Americans.”

Shepard dropped the smuggled golf ball and prepared to take a shot. The constraints of the suit forced him to swing his improvised golf club with one hand and on his first attempt he merely buried the ball in the dust.

“You got more dirt than ball that time,” observed Ed Mitchell.

“Got more dirt than ball.” agreed Shepard. “Here we go again.”

|

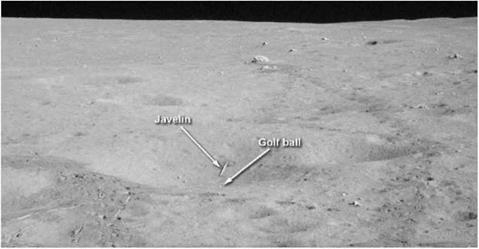

The final resting places of one of Shepard’s golf balls and Mitchell’s ‘javelin’. (NASA) |

His second shot connected to move the ball about a metre, though in the wrong direction.

"That looked like a slice to me, Al,” said Fred Haise in Houston.

"Here we go,” said Shepard. “Straight as a die; one more.”

He was successful at the third attempt and also gave a second ball a clean hit, sending them both soaring into the distance.

"Miles and miles and miles,” he said as the second ball flew off.

"Very good, Al,” said Haise.

Mitchell also tried a little sporting activity during their final moments when he threw the support for the solar wind experiment, javelin style, as far as he could. Both the javelin and one of Shepard’s golf balls ended up in a small crater about 25 metres away.

After Shepard’s indulgent golf swing, David Scott focused on science in his earnest demonstration of high-school physics. He and Joe Allen, his Capcom during his surface exploration came up with the idea of dropping a hammer and feather simultaneously to show viewers that, as predicted by well established theory, both masses would fall at the same speed. Scott was worried that static electricity might ruin the experiment and had brought two feathers, one to rehearse with and one for the TV. In the event, he did not have time for the trial run and hoped it would work first time, which it did. Allen was subsequently responsible for a chapter in Apollo 15’s Preliminary Science Report that summarised the scientific results of the mission. Among the more obscure descriptions of the various experiments and investigations was this paragraph, written with perhaps a hint of tongue-in-cheek humour:

"During the final minutes of the third extravehicular activity, a short

demonstration experiment was conducted. A heavy object (a 1.32-kg aluminum

geological hammer) and a light object (a 0.03-kg falcon feather) were released

simultaneously from approximately the same height (approximately 1.6 m) and were allowed to fall to the surface. Within the accuracy of the simultaneous release, the objects were observed to undergo the same acceleration and strike the lunar surface simultaneously, which was a result predicted by well – established theory, hut a result nonetheless reassuring considering both the number of viewers that witnessed the experiment and the fact that the homeward journey was based critically on the validity of the particular theory being tested.’’

Flaying with gravity was the theme of John Young’s signature stunt on Apollo 16. During their first EVA, when he and Charlie Duke were working around the LM, they took time out for the almost obligatory tourist shot of each crewman saluting next to the Stars and Stripes.

‘ Iley. John, this is perfect.” said Duke gleefully, ‘with the LM and the rover and you and Stone Mountain. And the old flag. Come on out here and give me a salute. Big Navy salute.”

“Look at this," said Young.

lie worked his arm so the suit’s cables would permit a salute then promptly launched himself nearly half a metre off the ground. Young’s total mass was about 170 kilograms including his suit and FLSS. But on the Moon it felt more like 30 kg and with barely a twitch of his legs and feet, he jumped a second time. Duke took a photograph at just the right moment to show Young apparently floating above the lunar surface.

As they wrapped up their final EVA. Young and Duke decided to Lake lunar athletics a stage further. Using the rover to steady himself. Young began to jump, getting higher each time until he reached a height of 70 centimetres. “We were gonna do a bunch of exercises that we had made up as the Lunar Olympics to show you what a guy could do on the Moon with a back pack on, but they threw that out.” “For a 380-pound guy, that’s pretty good,” said Tony England, their Capcom. Having seen his commander go ahead with some simple athletics, Duke decided to join in with a leap of his own. "Wow!” he exclaimed as he saw how high he could rise but as he descended, he realised that he had imparted a little backwards rotation. In his slow-motion fall, and with a moment of fear and panic welling up inside, he realised that he was going to fall onto his PLSS.

“Charlie!” called Young. The FLSS was not designed to Lake a fall like this. “That ain’t any fun, is it?" said Duke sheepishly as he lay on his PLSS facing upwards.

“Thai ain’t very smart,” pointed out his commander.

“That ain’t very smart,” agreed Duke trying unsuccessfully to turn over. “Well, I’m sorry about that.”

Young saw how much dust he was going to have to brush off Duke’s suit. “Right. Now we do have some work to do.”

“Agh! How about a hand. John?”

All the crews took a childish delight at throwing things in the weak lunar gravity. They were especially impressed at how bulky but light items like sheets of plastic foil would sail off in perfect ballistic trajectories undamped by air resistance. At the end

of the final EVA on the Moon’s surface, Gene Cernan saw a chance for a really good throw. He and Jack Schmitt shared a geology hammer and there was now no further use for it. ‘‘You ready to go on up?” he asked of Schmitt.

“Well, I don’t know,” replied Schmitt who then rattled off a list of further tasks remaining.

“Well, watch this real quick.”

When Schmitt saw what Cernan was about to do with their one geology hammer, his own boyish instinct kicked in. “Oh, the poor little… Let me throw the hammer.” After all, he was the geologist, ft only seemed correct that he should get to throw the geology hammer.

Cernan acceded. “It’s all yours. You deserve it. A hammer thrower. You’re a geologist. You ought to be able to throw it.”

Cernan acceded. “It’s all yours. You deserve it. A hammer thrower. You’re a geologist. You ought to be able to throw it.”

Schmitt took the hammer away from the spacecraft and prepared to throw it. “You ready?”

“Go ahead,” said Cernan.

“You ready for this?” repeated Schmitt, building up to the great moment. “Ready for this?”

“Yeah,” said Cernan, then added a warning. “Don’t hit the LM. Or the ALSEP.”

Schmitt brought his arm back and swung with his whole body to launch the hammer in front of the LM.

“Look at that!” cried Cernan as the hammer arced out over the landing site, over their footprints and their wheeltracks and over all the discarded gear they were about to leave behind, perhaps for eternity. “Look at that! Look at that!”

After a flight lasting seven seconds, long enough for Cernan to take a series of pictures of its coast, it landed halfway to the ALSEP site in a plume of dust, where it still lies. “Beautiful,” said Schmitt. “Looked like it was going a million miles,” said Cernan, “but it really didn’t.”

“Didn’t it?