“Okay. Another crater."

Navigation on the lunar surface was of no concern to Armstrong and Aldrin. They never ventured more than 60 metres from the LM. But as the crews of Apollos 12 and 14 made their H-mission traverses it became increasingly difficult to tell where they were as they roamed further on foot to locate features of scientific interest that geologists had identified from aerial photographs. At close quarters, the lunar surface is remarkably homogenous, especially on the plains. Huge areas consist of little more than large, time-worn craters pockmarked with smaller craters, all covered with a ubiquitous layer of grey dust and shattered rock.

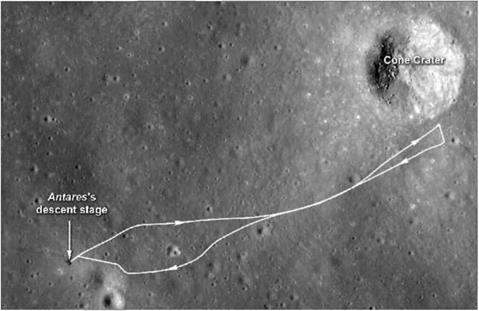

The issue came to a head as A1 Shepard and Ed Mitchell set off to reach the rim of Cone Crater, their primary scientific target. Seen from above, Cone was a majestic 1,000-metre-wide hole in the ground but it was surrounded by a landscape that, at a human scale, w7as unrelentingly undulating. Worse, they had to climb a rough slope to reach it and since from their perspective atop the ridge the far rim of the crater was lower than its near rim, it would remain invisible until they were almost at its edge. It had been thought that the crater would have a raised rim that would make it easy to locate.

“Okay. We’re really going up a pretty steep slope here,” puffed Mitchell as his heart rate peaked at 128 beats per minute.

“Yeah. We kind of figured that from listening to you,” said Fred Haise in Houston. The heart rate of Shepard, a much older man at 47, had just risen to 150 as the effort of their climb and the frustration of their inability to locate the rim of Cone began to tell.

As the two laboured up the ridge, they pulled a little hand cart, the modular equipment transporter (MET) which was the engineers’ answer to the shortcomings of the hand tool carrier. It not only provided a place for the tool carrier, it allowed a much larger range of tools to be taken on a walking traverse as well as cameras, film magazines and sample bags; and it permitted a greater weight of rock to be returned to the LM. The MET rolled along on two rubber tyres pressurised with nitrogen. It was of some surprise to the crew that the wheels did not throw up rooster-tails of dust, but rather formed smooth ruts in the soil that reflected the Sun when viewed into the light. Included with the MET was a magnetometer to measure the local magnetic field at points along the way to Cone. Its sensors were mounted on a tripod which was deployed on the end of a 15-metre cable. After allowing time for the unit to settle, readings were gathered from a unit on the MET itself.

|

The modular equipment transporter, photographed from the window of Antares, the Apollo 14 lunar module. (NASA) |

"I thought the MET worked very well." said Shepard alter the flight. "It enabled us to operate more efficiently than we would have otherwise.”

Mitchell agreed. "’We would have been in real trouble trying to move all that stuff out with just a hand tool carrier, and still get the same amount of work done.”

Thick soil and an increasing incline were adding to their difficulties. "The grade is getting pretty steep,” warned Mitchell, clearly breathing heavily. "And the soil here is a bit firmer, 1 think, than we’ve been on before. We’re not sinking in as deep."

"‘That should help you with the climb there.” said Haise encouragingly.

"’Yeah. It helps a little bit.”

Shepard had another way of making the climb easier.

"’Al’s got the back of the MET now, and we’re carrying it up. I think it seems easier.”

"Left, right, left, right,” prompted Shepard as he tried to quicken their progress up to Cone.

The backup crew of Gene Cernan and Joe Engle were listening in next to Haise. "There’s two guys sitting next to me here that kind of figured you’d end up carrying it up."

“Well, it’ll roll along here,’’ explained Mitchell, "except we just move faster carrying it.”

Always mindful of the need to return before their consumables ran out, and having already awarded a 30-minute extension, mission control enquired of their progress.

"Л1 and Ed. do you have the rim in sight at this Lime?”

"’Oh, yeah,” confirmed Mitchell.

"’It’s affirmative.” said Shepard. "It’s down in the valley.”

But they had misheard ’rim’ as ‘LM‘.

"’Em sorry,” said liaise. ""You misunderstood the question. I meant the rim of Cone Crater.”

"’Oh, the rim. That is negative,” said Shepard. “Wc haven’t found that yet.”

The problem they faced was that they were being fooled by the terrain that surrounded the crater and. by heading for the highest ground, they were being taken south, to one side of their goal. They were not lost in the strict sense of the word. The LM was easily visible from their elevated route and there would be no difficulty in finding their way back. On behalf of mission control, Haise called a halt to the quest. "Ed and Al. we’ve already eaten in our 30-minute extension and we’re past that now. I think we’d better proceed with the sampling and continue with the EVA.”

It was a bitter moment for the two explorers. They had come 400.000 kilometres to the Moon and had laboured uphill for over a kilometre to sample the deepest ejecta from the rim of Cone Crater. The superficial metric of their success would have been to take possibly spectacular pictures that looked across the crater to its far rim.

"It was terribly, terribly frustrating,” remembered Mitchell twenty years later, on how it felt to have seemed to have failed. "Coming up over that ridge that wc were

|

Shepard and Mitchell’s route up the flank of the ridge to reach Cone Crater. Site photograph by Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2009. (NASA) |

going up, and thinking, finally, that was it; and it wasn’t – suddenly recognizing that, really, you just don’t know where the hell you are. You know you’re close. You can’t be very far away. You know you got to quit and go back. It was probably one of the most frustrating periods I’ve ever experienced. There’s no feeling of being lost. I mean, the LM is there; we can get back to the LM. It’s not reaching and looking down into that bloody crater. It’s terribly frustrating.”

Like most of the Apollo astronauts, Mitchell came from a high-achieving military background and was used to reaching goals that had been set. This particular goal was also the pinnacle of a crewman’s career and the apparent failure was a blow to a pilot’s pride. But in truth, Apollo 14 admirably fulfilled the scientific task it had been set. Their objective was to gain deep samples from the rim of Cone and since their closest sampling point was later established to be only about 30 metres from the true edge of the 1,000-metre crater, they had, without realising it, been successful.