GOING FOR A WALK

There was little opportunity on Apollo 11 for Armstrong or Aldrin to wander far from the LM. Their time outside was so brief and they had been given so much to do. Lven though their PLSSs were capable of supporting a 4-hour moonwalk, managers had kepi this initial single excursion down to only 2Vi hours, and then packed that Lime with an enormous range of tasks. One of Aldrin’s tasks was to investigate their mobility in this new environment. This he would do in front of the TV camera.

“Td like to evaluate the various paces that a person can [adopt when] travelling on the lunar surface." He readied himself to walk towards the camera and across its field of view and then he began to narrate his various strides. "You do have to be rather careful to keep track of where your centre of mass is." Since lunar gravity did not bear down nearly as much as on Earth, the brain was less aware of where the centre of mass was. "Sometimes, it takes about two or three paces to make sure you’ve got your feet underneath you."

Aldrin’s first display w as a loping stride on alternating feet as he headed towards the camera, but his lightness meant that for much of the time, both feet were off the ground as each leg launched him forward on what was really the first example of running on the Moon. His inertia was much more of an issue because while his weight was reduced, his mass and that of his suit were unaltered and once in motion, they took conscious effort to bring to a halt. "About two to three or maybe four easy paces can bring you to a fairly smooth stop." He continued his stride away from the camera, deliberately changing direction a few7 Limes so everyone could see. "[To] change directions, like a football player, you just have to put a foot out to the side and cut a little bit."

So much for a walk/run. Next he tried bouncing, with two feet pushing forward together as he returned towards the camera. “The so-called kangaroo hop docs work, but it seems as though your forward mobility is not quite as good as it is in the more conventional one foot after another."

"I felt it was quite natural,” said Armstrong after the flight as he described his mobility on the lunar surface. "The one-sixth gravity was. in general, a pleasant environment in which to work, and the adaptation to movement was not difficult.’’ Planners had worried about how’ well humans would cope with a hugely reduced gravity, and this had been one of the reasons for the very conservative extent of the Apollo 11 EVA. Prior to the flight, many schemes were pursued to simulate sixlh-g and give astronauts a flavour of what to expect, but in the event, they adapted with ease. "In general, we can say it was not difficult to work and accomplish tasks." commented Armstrong. "I think certain exposure to one-sixth g in training is worthwhile, but I don’t think it needs to be pursued exhaustively in light of the ease of adaptation."

Despite the rules that bound them to the TV camera’s field of view7, Armstrong pushed the envelope a little. Townrds the end of their excursion, he decided to go for a short run and headed 60 metres behind the LM to a small crater he had overflown on the way down. For the brief moments he could be seen, it was clear he had settled into the same loping gait that Aldrin had just demonstrated and which most of the moonwalkers wnuld adopt.

Ed Mitchell, Charlie Duke and Gene Cernan often used a gait that was in between the foot-by-foot lope and the kangaroo hop. In this, they pushed off on both feet but always kept a given foot in front of the other while landing w ith the rear foot slightly earlier than the front foot.

After the conservatism of the first moonwalk, Apollo’s managers let the program move up a gear to extend the reach of subsequent crews. Conrad and Bean used their first 4-hour EVA to set up science instruments. Then with a little time left over, they went 180 m beyond their new science station to the rim of a big crater to take some pictures. Their second EVA, also for four hours, was devoted to a walk of over 1.3 kilometres that made a great loop around a series of geological targets. The furthest of these was a small, fresh (meaning a few million years old) crater called Sharp sited 400 metres from the LM.

The two astronauts hustled around their circuit, loping easily from site to site in their bulky suits at about four kilometres per hour to give themselves as much time as possible at their stops. The early model of the suit was very stiff at the waist and this restriction made walking hard work when compared to the more flexible suits worn by the J-mission crews. During part of their journey, as they headed from Sharp to another crater, this one called Halo, Bean felt a change in the apparent air pressure in his suit that was later attributed to his vigorous movement causing the flow of air out of the suit to be momentarily interrupted, producing an overpressure that he felt in his ears.

The stiffness of their suits also made it difficult to kneel down and pick up rock. Though they had tools to help them, Bean came up with another idea when Conrad was about to go for another sample on the southern rim of the Surveyor Crater. "Wait, Pete. Eve got an idea.”

"What?”

"Pete, let me reach back here and grab this strap.” The strap was part of a bag attached to the rear of Conrad’s PLSS that was to carry parts from the Surveyor 3 probe they were about to visit. Bean realised that in the weak gravity, he could use this to lower his commander to the surface without Conrad having to bend his knees.

"Pete, let me reach back here and grab this strap.” The strap was part of a bag attached to the rear of Conrad’s PLSS that was to carry parts from the Surveyor 3 probe they were about to visit. Bean realised that in the weak gravity, he could use this to lower his commander to the surface without Conrad having to bend his knees.

Since they had found the scoop to be a little tricky to use in the light gravity, Bean’s trick avoided it and allowed Pete to use both hands to reach out for the rock directly.

"That a boy,” said Conrad once he had the rock firmly in his hand. "[Pull me] back up!” The two astronauts were adapting and improvising in their new domain. Bean thought it would be useful technique for the next crew to visit Luna’s surface.

"Now, if they had a strap like that, they could just hold the other guy while he leaned over and picked up a

rock.” In the event, such clever techniques were rendered obsolete by the greater flexibility of later suits.

An additional problem that became apparent on their walk was that they had a lot of equipment. To help them, they had the hand tool carrier (HTC), a small, threelegged truss structure that not only held their tools, like a hammer, corer and scoop, it also had a bag in the centre to give them somewhere to place rock samples gained during their long traverse. A handle extended upwards to give the crewman something to grasp. "Boy, this hand tool carrier is light and nice compared to carrying it around on Earth,” said Bean as he began their long walk. Though it helped a lot, it could cause problems of its own, as Bean discovered when he tried to make a faster pace across the surface. “I’m carrying that thing and that interferes with your running,” he later explained. "You can’t run good, because it bumps into your legs and it’s just a big hassle. And it gradually got heavier because we kept putting rocks in it.”

The fact that it had to be grasped by a handle also raised a continuing difficulty that anyone in a pressurised spacesuit faces when they have to hold objects for a long period – they have to overcome the stiffness of their gloves. Under pressure, the gloves, like the rest of the suit, tried to adopt a particular posture which, for the Apollo suit, had the hands slightly outstretched with the fingers and thumbs curled inward a little. To grasp an object for a long period, the crewman had to constantly work against this pressure to maintain his grip around an object and soon, his forearm muscles would tire.

|

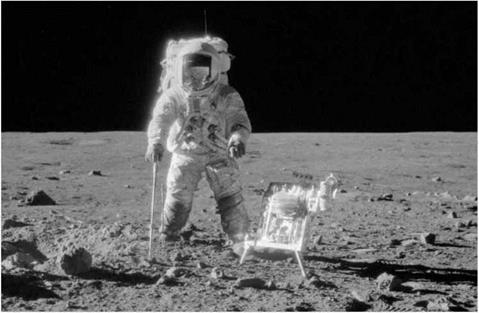

Pete Conrad near Surveyor Crater. Beside him is the hand tool carrier. (NASA) |

Before the flight, Bean had tried to physically condition himself for the mission’s arduous workload hut after the flight he said that if he had properly understood the exertions he would have modified his approach. “The big pain with that tool carrier is that you have to hold it out from your body so that your legs don’t bump into it as you walk, which means you have to hold it by one hand. That’s not a big deal when it’s light and there are no rocks in it; but when you start filling it with rocks, it gets to be a pretty good stunt to hold it out there for long periods of time. I was running two and a half miles a day towards the end of the training period to get my legs in shape, and my legs never suffered a bit. If I had it to do over again, I would run about a mile a day and spend the rest of the time working on my arms and hands, because that’s the part that really gets tired in the lunar surface work.” Indeed, Bean passed this adviee onto his successor, Fred Haisc, while still on the Moon.

Though Conrad did not have to haul the tool carrier around, he found he had other problems with his hands. “I didn’t notice that my hands got tired as much as I noticed that they got sore. When you work for four hours and use your hands, you have a tendency to press the end of your fingertips into the end of the gloves. Although my hands never got stiff or tired, they were quite sore the next day when we started the second EVA.”

Bean pointed out another phenomenon in his gloves when working with the tool carrier. "Iley. one thing I’ve noticed, Houston, carrying the tools. You don’t feel any of the temperature here. Sun’s out nice and bright, but it’s nice and cool in [the suit]; except when you’re carrying something metal, like the hand tool carrier, or the shovel, or something. Then your hand starts to get warm." At first, he attributed this to the metal being heated in the direct sunlight, but he later reassessed the cause. "Maybe it isn’t that the tool is hot. When you grip your hand around there, then the air can’t flow in your hand area any more. So your hands don’t have the air circulation they normally do. Before, they were just kind of floating in the middle and the air’s being blown around. But once you grip, then the air can’t get down in there.’’