First moments

"Tm at the foot of the ladder.” Neil Armstrong brought a quiet coolness to the moments before he took humankind’s first step on the Moon. "The LM footpads are only depressed in the surface about one or two inches, although the surface appears to be very, very fine grained, as you get close to it. It’s almost like a powder. [The] ground mass is very fine.”

Armstrong was not telling science anything it did not already know. Previous unmanned probes and objective theorising by lunar geologists had established that the lunar surface would be finely powdered, beat up from an incessant rain of objects over extremely long time periods. But, first and foremost, Armstrong was an engineer and test pilot and one of the best in the business. What test pilots do is observe and describe in physical terms, and that was exactly what he was going to bring to this endeavour.

“I’m going to step off the LM now.”

With his right hand holding onto the ladder. Armstrong placed his left foot onto the dust of Marc Tranquillitatis. "That’s one small step for [a] man; one giant leap for mankind.’’

With the moment appropriately marked, Armstrong continued onto the surface and tentatively began to adapt to moving around in the weak gravity field. He also returned to his descriptive roots. "Yes. the surface is fine and powdery. I can kick it up loosely with my toe. It does adhere in fine layers, like powdered charcoal, to the sole and sides of my boots.”

In the years leading up to this moment, one scientist had attracted the attention of the press, ever hungry for a story, by suggesting that the LM or an astronaut would be swallowed up by a great depth of dust which, he theorised, would have taken on a Tairy-castlc’ structure. Thomas Gold’s theory was based on interpretations of radar observations which showed that the surface consisted of very loose material, which is indeed an accurate description of the Lop few millimetres. However. Gold took this observation and wove it into a tale of great seas filled with electrostatically supported dust. In fact, the large size of the LM footpads is attributed to his influence. Gold continued to provide reporters with a yarn of possible catastrophe even after unmanned Surveyor landing craft had successfully touched down using footpads designed to impart the same pressure as the LM pads. These spacecraft also returned images of boulders resting on the surface and orbiting spacecraft had imaged great swathes of ejected blocks from large craters that had clearly not sunk into the dust. But of this period, geologist Don Wilhelms wrote, "One would think that the presence of all this dust-free blocky material would have weakened the Gold-dust theory, but no amount of data can shake a theoretician deeply committed to his ideas.”

Armstrong was demolishing such worries once and for all. "I only go in a small fraction of an inch, maybe an eighth of an inch, but I can see the footprints of my boots and the treads in the fine, sandy particles."

Always aware that a problem could cause the EVA to be terminated at any Lime, Armstrong’s initial moments on the surface were carefully planned. He had a short moment to ensure he would have no difficulty moving around, then he and Aldrin used a looped strap to send a Hasselblad camera down from the cabin. The hmar equipment conveyor (LEC) was NASA’s reply to a fear that it might be difficult and time-consuming to carry items up and down the ladder, particularly boxes of rock samples. The LEC w-as discarded after Apollo 12 as crews came to better understand the ease with which heavy loads could be handled on the Moon. With the camera attached to a bracket on his chest mounted RCU. Armstrong proceeded to take a series of overlapping pictures that could later be merged into a panoramic view of the landing gear. Then, after a reminder from Bruce McCandless in Houston, he used a scoop to gather a contingency sample of the soil near Eagle.

"Looks like it’s a little difficult to dig through the initial crust,” noted Aldrin from Eagle’s cabin.

"This is very interesting,” said Armstrong. "It’s a very soft surface, but here and there where I plug with the contingency sample collector, I run into a very hard surface. But it appears to be a very cohesive material of the same sort.” Armstrong

|

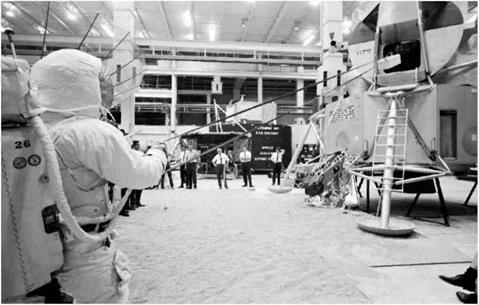

Neil Armstrong practises using the lunar equipment conveyor three months before Apollo ll’s flight. (NASA) " |

had discovered what is, to people used to Earth, an odd property of the soil. This part of Mare Tranquillitatis had seen essentially no volcanic activity for well in excess of three billion years. The only large scale processing of the rock had been by countless impacts, and the vast majority of these were small. Each had helped to pulverise the surface into a layer of dust and boulders about five metres thick called the regolith and each had served to shake the subsoil until it became extremely well compacted yet unconsolidated material. So while the top few centimetres were loose, the subsurface seemed hard and unyielding.

It was then Aldrin’s opportunity to climb down the ladder as Armstrong photographed him. “Now I want to back up and partially close the hatch, making sure not to lock it on my way out.”

“A particularly good thought,” laughed Armstrong.

“That’s our home for the next couple of hours and we want to take good care of it.” The checklist had called for the hatch to be partially closed, probably to prevent the shaded interior radiating its heat into space.

Ever the test pilot, Aldrin continued to narrate his descent of the ladder. “It’s a very simple matter to hop down from one step to the next.”

“Yes. I found I could be very comfortable, and walking is also very comfortable. You’ve got three more steps and then a long one.”

Aldrin practised leaping between the ladder and the footpad, then, before he stepped onto the surface, he turned to take in the landscape.

“Beautiful view!”

‘‘Isn’t that something!” said Armstrong. “Magnificent sight out here.”

“Magnificent desolation.”

Snow on the Moon

As A1 Bean waited to follow’ Pete Conrad out of Intrepid’s cabin, he moved to his window to adjust a movie camera that would record their work on the surface. Just after Conrad had taken a contingency sample of lunar soil, both men heard a warning in their headsets.

“Uh-oh, did I hear a tone?” said Conrad as he tested his mobility on the surface.

“Yeah; I’ve got an H20 A,” said Bean.

“You do?”

“Yeah. I wonder why?”

The ‘A’ flag and tone was telling Bean that his cooling system wras failing. For a few’ minutes he tried to troubleshoot the balky PLSS as Conrad got started on tasks around the LM.

“Okay. I think I know what happened. Houston.” said Bean as he spotted the cause. After the flight, he explained the circumstances: "1 happened to glance down and noticed the door was closed. I realised what had happened. The outgassing of my sublimator had closed the door, with the result that I didn’t have a good vacuum inside the cabin anymore. I quickly dove to the floor and threw back the hatch. The minute I did. a lot of ice and snow went out the hatch.”

“What did you just do, Al?” asked Conrad when he saw’ resultant display.

“Man, I just figured it out.”

“You sure did. You just blew water out the front of the cabin.” Then correcting himself, “Ice crystals.”

“That’s what had happened to the PLSS. The door had swung shut, […] and probably bothered the sublimator. ‘cause it wasn’t in a good vacuum anymore. So 1 opened the door and it’s probably going to start working in a minute.”

“I should hope so. laughed Conrad. "When you opened the door, that thing shot iceballs straight out the hatch.”

The first time David Scott opened Falcon s forward hatch, he treated Jitn Irwin to a similar display of ice particles visible out of his window. “It’s blowing ice crystals out the front hatch,” laughed Irwin. “It’s really beautiful. You should see the trajectory on them.”

“I bet they’re Паї, aren’t they, Jim?” asked Capeom Joe Allen. “The trajectories?” Allen wras a scientist by training and as soon as he heard about the flying crystals, he immediately began to think about how they would move.

“Very flat. Joe,” answered Irwin to Allen’s query.