Where are we?

As mission control worked towards a final decision to stay, and as the crew got on with their tasks, there was usually some discussion about how close to their target point they had managed to land. Armstrong had known long before touchdowm that he and Aldrin w’ere going to land w’ell past their intended destination. Shortly after arrival at Tranquillity Base, he raised the question with Houston. "The guys that said that we wouldn’t be able to tell precisely where we are. are the winners today.” It was no great surprise, given the hair-raising nature of their descent. "We were a little busy worrying about program alarms and things like that in the part of the descent w’here w’e w’ould normally be picking out our landing spot.” he continued, "and aside from a good look at several of the craters w? e came over in the final descent, I haven’t been able to pick out the things on the horizon as a reference as yet.”

‘;No sw’eat,” reassured Charlie Duke in mission control. "We’ll figure it out.”

It took a long Lime for anyone to figure it out. Throughout the time he spent in orbit alone, Mike Collins never once managed to view’ Eagle through the sextant, which was hardly surprising, given that it had landed six kilometres from its intended site and the plain of Mare Tranquillitatis is a featureless wasteland of crater imposed

|

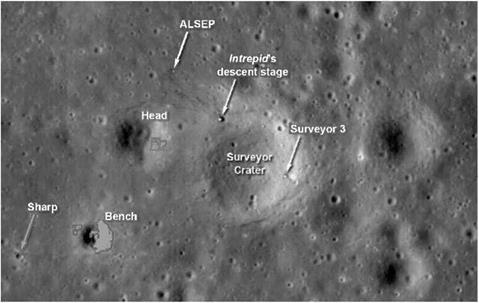

The Apollo 12 landing site, photographed 40 years later by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. (NASA) " " |

upon crater. The best estimate was made by the geological team at mission control who noted how Armstrong had described flying over a large blocky crater to a "fairly level plain with a large number of craters”.

The factors that led to the inaccuracy of the Apollo 11 landing were overcome to guide Pete Conrad to a pinpoint landing on Apollo 12. He knew where he was, but had trouble telling mission control because he was reading the map incorrectly. Four hours later, as Dick Gordon coasted overhead in Yankee Clipper, he had his eye firmly affixed to the sextant eyepiece.

"Houston, I have Snowman.” The familiar pattern of craters stood out when the computer was asked to point the optics at the intended landing site. At first, he confused Intrepid with the Surveyor 3 spacecraft that had arrived 31 months earlier. Then it clicked.

"I have Intrepid. I have Intrepid,” said Gordon excitedly. "He’s on the Surveyor Crater; he’s about a quarter of a Surveyor Crater diameter to the northwest.”

"Roger, Clipper. Well done,” replied Capcom Ed Gibson. Surveyor Crater formed the torso of the Snowman and was where the eponymous spacecraft had been located.

"I’ll tell you, he’s the only thing that casts a shadow down there.”

If the planned walking traverses to geologically interesting sites were to be fulfilled, an accurate landing was mandatory for Apollos 12 and 14. Just 600 metres off could make a destination unreachable. Alan Shepard brought Antares down within a mere 50 meters of his target, the best of the programme, but for the J – missions, only the commander’s bragging rights were in jeopardy by such a miss. Having a rover rendered such inaccuracies moot.