From Toys to Gliders

Wilbur Wright was born April 16, 1867; Orville on August 19, 1871. As children, the brothers played with a toy helicopter that was driven by a twisted rubber band. Rubber-powered flying machines, invented in the 1870s by Frenchman

Alphonse Penaud, were popular toys. Such toys also helped inspire young inventors, including the Wright brothers. The young Wrights went into business, first as printers and then as bicycle makers. In their spare time, they built and flew kites. They became interested in the possibilities of human flight after reading about the pioneering experiments of Otto Lilienthal in Germany and Octave Chanute in the United States.

Lilienthal was killed in 1896 when his glider flipped over in midair. This accident convinced the Wright brothers that Lilienthal’s gliders did not have the right wings or control surfaces for safe, manned flight. They tested different wing shapes in a wind tunnel they built themselves. Then the Wrights brought their gliders from their home in Dayton, Ohio, to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Kill Devil Hill, a large sand mound at Kitty

|

Hawk, was a good place for test flights with few inquisitive spectators.

From 1900 to 1902, the Wrights flew three large gliders that carried a person. Flying the gliders, the brothers learned how to control the flimsy craft, using a system of “wing-warping” (altering the angle of the tips of the wings) to control the balance of the airplane. In the modern airplane, ailerons and elevators are used for this purpose, but the Wrights had to learn by experimenting to overcome the stability problems that had cost Lilienthal his life. In their wingwarping system, wires were attached to the wingtips and fastened to the pilot’s hips. By shifting his body position, the pilot could twist (warp) the tip of the wing to maintain control of the airplane. This method seemed to work in a glider, but would it work in a flying machine powered by an engine?

Building the Flyer

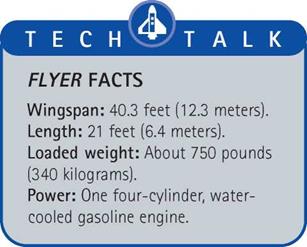

An airplane engine had to be small and light. No vehicle engine of the time was suitable, and so the only option for the Wright brothers was to build their own. They built a gasoline engine with a power output of 12 horsepower (9 kilowatts). The brothers fitted the engine into a flimsy-looking airplane, much like the gliders they had already flown but with two propellers. They optimistically named their new machine the Flyer.

The Wright Flyer was a biplane with a total wing area of 510 square feet

|

|

(47.5 square meters). The wings consisted of wood frames covered with cloth. The aircraft’s little gasoline engine was linked by chains to two wooden propellers, each 8.5 feet (2.6 meters) in diameter. One chain was crossed over so that the propeller it drove rotated in the opposite direction to the other. These contra-rotating propellers helped balance the airplane.

(47.5 square meters). The wings consisted of wood frames covered with cloth. The aircraft’s little gasoline engine was linked by chains to two wooden propellers, each 8.5 feet (2.6 meters) in diameter. One chain was crossed over so that the propeller it drove rotated in the opposite direction to the other. These contra-rotating propellers helped balance the airplane.

The Flyer looked strange compared with most later airplanes. Its “tail” was at the front, and the propellers faced backward, as “pushers.” Very little was known about designing airplane propellers, and the Wrights (who made their own propellers from wood) had to experiment to see which kind worked best. Aviation pioneers copied the screws used on steamships or the sails fitted to windmills, but neither was ideal for an airplane propeller.

To launch the airplane, the Wrights laid down a wooden rail 60 feet (18.3 meters) long. The airplane sat on a dolly-a small cart with two bicycle hubs

for wheels-that ran along the rail. The idea was that, as the engine pushed it along, the Flyer would lift off the dolly into the air and fly.