SLOWING DOWN: P63

"Ignition.” announced Armstrong to Aldrin as Apollo 1 l’s LM Eagle began the human species’ first descent to another world.

“Ignition,” repeated Aldrin. “Ten per cent.”

On all the missions, at PDI the DPS engine was initially run at only 10 per cent of its maximum thrust for 26 seconds to give the computer enough time to sense whether the engine’s thrust was acting through the LM’s centre of mass, and if it was not. to move its supporting gimbals until it was. This ability to vector the thrust was not intended to steer the craft. It was too slow for that. Steering was provided by the RCS thrusters which altered the attitude of the entire craft to aim the thrust, leaving the engine’s gimbals to deal with longer-term centre-of-mass shifts.

Aldrin counted up to the end of the low-thrust phase. “24, 25. 26. Throttle up. Looks good!” Propellants poured into the engine as it went to its high-thrust setting.

Starting with Apollo 12, engineers added a modification to the computer’s programming to achieve pinpoint landings. As soon as Intrepid came around the Moon’s limb prior to landing, its velocity was compared with what would be ideal to achieve a pinpoint landing. From this, engineers could calculate the difference between where they wanted to land and where the computer, which believed it was on the right course and unaware of external factors which had perturbed its path, was actually taking them.

“Intrepid, Houston,” called Capcom Gerry Carr only 80 seconds into Apollo 12’s powered descent. “Noun 69, plus 04200. Over.”

“Roger. Copy. Plus 04200," confirmed Bean.

This was the important call that ensured that the LM would land where it was

supposed to, and it was extremely dangerous. Noun 69 held three values that represented an update to the position of the landing site in three dimensions. Changing one of those values by +4,200 feet (1,280 metres) shifted the computer’s idea of where they should land to a point further downrange, thereby fooling it into taking them where they wanted to go. When the crew had punched the number into the DSKY’s register, mission control took a look at the telemetry to verify they had done so correctly before confirming that they could ‘enter’ it into memory. Had the crew inadvertently entered the wrong data, they could easily have sent the LM out of control and been obliged to abort.

“Intrepid, Houston. Go for Enter,” said Carr once he had received word from other flight controllers that the crew had typed the update into the correct field.

“It’s in, babe,” said Bean.

“Intrepid, Houston. Looking good at two,” replied Carr as they passed the 2-minute mark into the burn.

“Intrepid, Houston. Looking good at two,” replied Carr as they passed the 2-minute mark into the burn.

Throughout P63’s regime, the DPS engine had to fire more or less into the direction of travel, especially during the initial minutes. As long as it did so, the LM could make rotational manoeuvres around the engine’s axis. On Apollo 11, the first few minutes of powered descent were flown with the windows, and therefore the crew, facing towards the surface. Armstrong had a method of using the angle markings on his window to time the passing of landmarks below. Before ignition, it had given him a check of what their perilune altitude was going to be. This used the fact that the closer you orbit a body, the faster the landscape below appears to pass by. Then after the commencement of powered descent, he could compare the absolute time a landmark passed with a predicted time. Since they were travelling at about 1.5 kilometres a second, only a few seconds early or late signalled the extent of any miss. It was a simple but powerful technique.

“Looking good to us,” Capcom

Charlie Duke informed Apollo 11. "You’re still looking good at three. Coming up. three minutes."

"Okay, we went by the three-minute point early." said Armstrong. “We’re long." He w’as right, because they landed six kilometres further down-range from where they had planned.

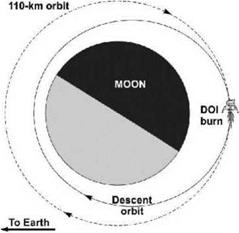

Conrad dispensed with the idea of having the windows looking down at the start of PD1 on Apollo 12 since they had other techniques in the wings to determine their approach errors. As soon as they entered the descent orbit over the far side, he placed the LM into the correct windows-up attitude for PDI. As this was an inertial altitude, set with respect to the stars, it was not concerned with the position of the Moon, so a windows-up, engine-first attitude over the near side of the Moon was a windows-down, engine-trailing attitude over the far side, as Pete Conrad explained: “From that inertial attitude, we watched ourselves pass from face down, through local horizontal [i. e. feet down, facing forward], to pitch up at PDI. It gave us an excellent look at the Moon going around.’’ It also gave their steerable antenna a clear view1 of Earth from AOS right through to landing.