THE JOYS OF LUNAR ORBIT

Whether they had entered the descent orbit or w’ere in the circular orbit that was a characteristic of the earlier expeditions, the crew had reached their quarry and. in most cases, could relax a little before the exertions of the next day: undocking, separation, descent and landing, along with, perhaps, a trip on the lunar surface. This was time to get out a meal, look after the housekeeping of the CSM and take photographs lots and lots of photographs.

How’ever, for the crew of Apollo 8 there was no time to relax. Once they had completed their LOI-2 burn, Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders had eight orbits and 16 hours remaining in the Moon’s vicinity. Their Lime was precious, and had been carefully rationed. Borman took care of actually flying the ship – not in the sense of sweeping over hills and dow:n valleys; orbital mechanics was the arbiter of their flight path. Instead, his job was to make sure that the spacecraft was aimed in

|

|

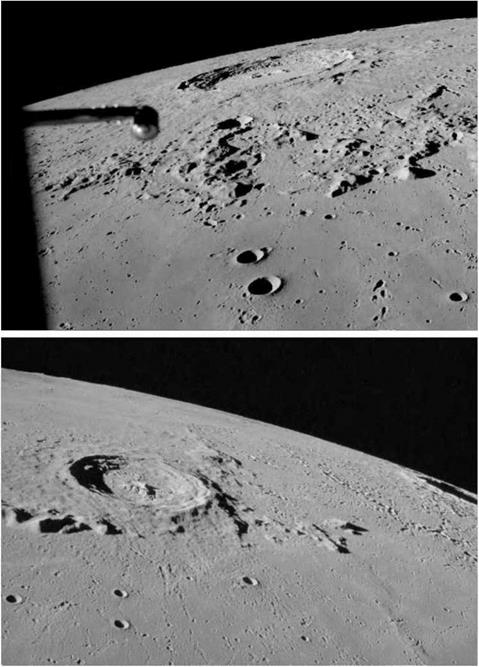

Two era-defining craters seen from Apollo 17. Top. Copernicus, about 900 million years old, still sports a clear ray system. Below. Eratosthenes is similar to Copernicus in structure but is old enough, about three billion years, to have lost its rays.

|

|

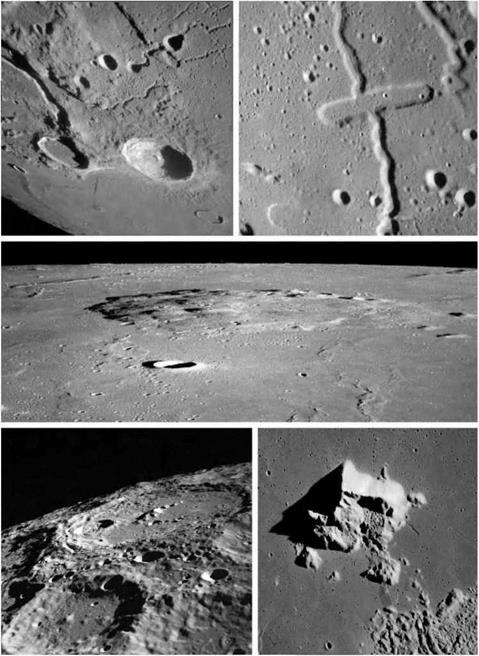

The view from orbit. Top left, Herodotus and Aristarchus among lava channels. Top right, Rimae Prinz and a lava-formed depression. Centre, Mons Riimker is a large, low volcanic mound. Bottom left, craters Stratton (foreground) and Keeler on the beat-up far side. Bottom right, central peak of Tsiolkovsky. (NASA)

whichever direction was required to satisfy the tasks of his colleagues. This became particularly important in view of their main windows having become fogged. To gain a clear view of the surface, they were left with only the two small forward-pointing rendezvous windows, whose narrow field of view was never intended to facilitate general photography.

Each orbital circuit was split into four by the geometry of the Sun and Earth with respect to the Moon, and this defined their tasks. Any task that involved working with mission control could only occur during a near-side pass. Anders’s prime responsibility was a programme of photographic reconnaissance of the Moon, and most of this work could only occur over the sunlit lunar hemisphere. Therefore, when they were over the night-time portion of the near side, he was free to check over the spacecraft’s systems and write down abort PADs from mission control. For about half an hour of each orbit, soon after AOS. the crew became especially busy as they approached Mare Tranquillitatis. As well as chatting to mission control, Lovell and Borman w orked together to view’ and photograph one of the planned landing sites, looking for visual cues that could be used by a landing crew’ and for obstacles that might pose a danger to a future lunar module.

Part of the reason for Apollo 8 going to the Moon, beyond the political act of getting one over on the Soviets, was to gain its much experience of lunar operations as possible before the landing missions were finalised. One of the techniques pioneered by this crew’ was the first use of the spacecraft’s guidance and navigation system, along with visual sightings of landmarks passing below-, to help to determine their orbit more accurately. Prior to the mission, a number of landmarks were selected for Lovell to view – through the spacecraft’s sextant. A mark was taken by pressing a button when a landmark was perfectly centred in the optics. From repeated marks and careful tracking from Earth, they were able to improve knowledge of the precise shape of the Moon, and also prove the techniques of lunar orbit navigation for future missions.

In addition to performing for the first time the unique tasks associated with flying next to another world, this crew continued to care for the spacecraft that was keeping them alive. Lovell occasionally took over the steering of the spacecraft while he looked for stars with which to realign the guidance platform. Anders looked after the environmental and propulsive systems, taking time out for a series of systems checks. All of their tasks were swapped around, allowing them, in turns, to gel some rest during this frenetic period as they tried to nurse their own exhausted metabolisms on a mission that, so far, had denied them adequate rest. Catching sleep when the other members of the crew were busy had proved impracticable on the way to the Moon. Trying to do so. as laid out in the flight plan, during the climax of humanity’s furthest adventure, proved even more difficult.

They had arrived tired and none of them could rest as they shared the excitement of seeing the Moon close up for the first time. By the seventh orbit. Borman began to notice that he was making mistakes. Worse, Lovell was having finger trouble with the computer. Aware that in a little over six hours they had to make a TEI burn to get themselves home, that they had a historic TV broadcast to make during the near-

|

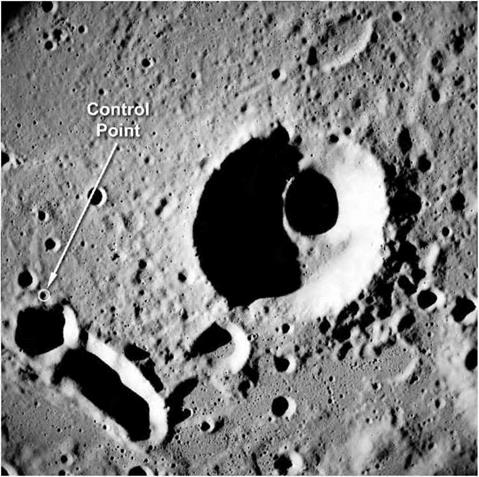

Landmark CP-1/8 next to a feature dubbed ‘Keyhole’ within a large far-side crater Korolev. (NASA) |

side pass prior to that bum and that they had all been awake for at least 18 hours, Borman took control. “I’m going to scrub all the other experiments, the converging stereo or other photography. As we are a little bit tired, I want to use that last bit to really make sure we’re right for TEI.”

To make sure that mission control understood what he intended, he specifically referred to the CMP tasks: “I want to scrub these control point sightings on this next rev too, and let Jim take a rest.”

Despite the can-do spirit of his colleagues, Borman stuck to his guns. “You’re too tired,” he admonished. “You need some sleep, and I want everybody sharp for TEI; that’s just like a retro.”

He was comparing the TEI bum to the retro bum used to get out of Earth orbit and return to the ground. In many ways the two types of bum had similar dire implications if they were to fail, except that, lor the latter, there might be a remote possibility of a rescue mission around the Earth. Anders realised that his commander wasn’t fooling and suggested a way of getting more science done wBile they rested: "Hey. Frank, how about on this next pass you just point it down to the ground and turn the goddamn cameras on; let them run automatically?"

"Yes, we can do that."

Mission control were used to having things done as prescribed, but understood the crew’s need for rest. Still, Capcom Mike Collins had to relay a request for exactly what was being cancelled. "We would like to clarify whether you intend to scrub control points 1, 2 and 3 only, and do the pseudo-landing site; or whether you also intend to scrub the pseudo-landing site marks. Over."

Borman was uncompromising. Only the success of the mission was important to him. If he sensed that their reconnaissance task was jeopardising their chances of getting home, he had no hesitation in dropping it. "We’re scrubbing everything. I’ll stay up and point – keep the spacecraft vertical and take some automatic pictures, but I want Jim and Bill to get some rest."

Mission control relented. Anders, being a typical driven perfectionist, tried again to continue with his tasks: “I’m willing to try it," he offered.

"You try it. and then we’ll make another mistake, like "Entering’ instead of "Proceeding’ [on the computer] or screwing up somewhere like I did."

When Lovell spoke up. Borman stood his ground. “I want you to get your ass in bed! Right now! No, get to bed! Go to bed! Hurry up! I’m not kidding you, get to bed!"

Despite their tiredness, the crew completed their 10 orbits around the Moon over Christmas and fired their engine for a safe THI and return home.