THE BLACK VOID

In the Christmas season of 1968, with a little over two hours to go before they entered lunar orbit, the CMP of Apollo 8, Jim Lovell, pointed out that despite their pioneering journey, something was missing.

“As a matter of interest, we have as yet to see the Moon.”

“Roger,” came the reply from Capcom Gerry Carr. He pondered this point for a few moments then sought a degree of elaboration.

“Apollo 8. Houston. What else are you seeing?"’

The acerbic reply from LMP Bill Anders shed new light on the truth of the astronauts’ great adventure.

“Nothing. It’s like being on the inside of a submarine.”

“Roger."’ was all Carr could say, for Anders’s comment was so true.

Despite being nearer to the Moon than any human in history, and with the exception of some sightings that Lovell had made through the spacecraft’s optics, this crew had yet to view their quarry. This was partly because their three large windows had fogged up owing to a design problem with the sealant around them. Additionally, they had spent most of their time during the coast broadside to the Sun. twirling slowly in the barbecue mode. In this attitude their two good windows, which looked along the direction the craft was pointed, viewed only deep space.

As with many of the Moon-shots, Apollo 8 arrived over the western side of the lunar disk at the same time as the Sun was rising over the eastern side. The nearer they got to the Moon, the closer it came into line with the Sun until, in the final few hours before arrival, the spacecraft entered the Moon’s shadow’ and plunged the crew into darkness. Apollo 10 arrived at the Moon under similar lighting conditions and its commander Tom Stafford still gained no view’ of the approaching planet.

“fust tried looking out as far as 1 can. out the top hatch window-, and still can’t see the Moon; but we’ll take your word that it’s there.’’ By ‘top hatch’. Stafford meant the round window in the side hatch, though as they lay in their couches, it was above their heads.

“Roger. 10. That’s guaranteed; it’s there,” said Charlie Duke in mission control. Stafford’s LMP Lugcnc Ccrnan couldn’t catch a glimpse of it cither, but the next time he journeyed to the Moon as the commander of Apollo 17, he got an eyeful.

“Boy. is it big! We’re coming right down on lop of it!” he shouted. “I’ll tell you, when you get out here, it’s a big mamou.”

Cernan was one of the few’ Apollo astronauts who had a natural ability to convey to the lay person some of the emotion and depth of the Moon-flight experience. Although he had been there before, the approach of this serene orb stunned him. and in his memoirs he expanded on this first glimpse.

“Looking at the Moon from our vantage point w’as quite unlike seeing it from Earth, w’hen it is so distant. Now’ it was gigantic, a world of its ow’n. and it forced me to question what I was really seeing. Such scenes existed only in science fiction, for not even the simulators could impart the reality of such a moment. We plummeted tow’ards it, faster and faster, and the closer w’e got. the bigger it grew-.’’

Cernan w’as also struck at how this extraordinary initial scene even managed to mute his LMP. geologist/astronaut and incessant talker. Jack Schmitt.

“Dr Rock was also stunned by the sheer size of the planetoid lhai he had spent a lifetime studying. Never in his wildest dreams had Jack imagined such a sight, and he momentarily lost his ability to even speak. The Sun illuminated the high peaks and mountains, and the rims of giant craters and surface details emerged, bathed in gold or hidden in deep shadow-.”

Apollo 11 was the first flight to afford an approaching crew a view of the Moon.

|

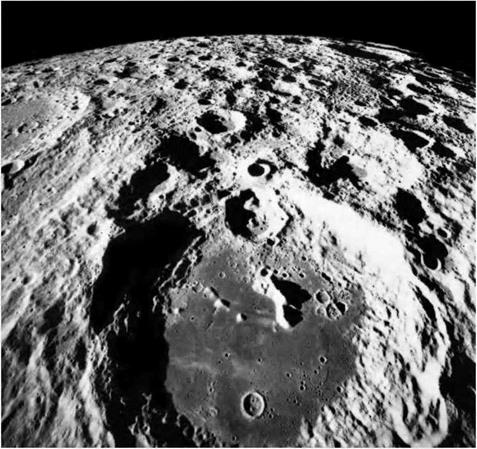

The Moon’s far side, as photographed by Apollo 17’s mapping camera. In the foreground is the 135-kilometre crater Aitken. |

They did not require a final mid-course correction, and this gave them the time and opportunity to turn the spacecraft around and for the first time see the Sun-blasted world they were about to explore loom in front of them. Mike Collins wrote about the shock he felt at what he saw.

“The change in its appearance is dramatic, spectacular and electrifying. The Moon I have known all my life, that two-dimensional, small yellow disk in the sky, has gone away somewhere, to be replaced by the most awesome sphere I have ever seen.”

This astronaut, one of the more poetic among the Apollo crewmen, had managed to glimpse the Moon at an opportune moment, just as they were about to enter its shadow. They then flew over an eerie landscape: the near side was dimly illuminated by Earthshine and a part of the far side which, owing to their vantage point was visible to them as a crescent, was as black as could be.

“To add to the dramatic effect, we find we can see the stars again. We are in the shadow of the Moon now. in darkness for the first time in three days, and the elusive stars have reappeared as if called especially for this occasion. The 360-degree disk of the Moon, brilliantly illuminated around its rim by the hidden rays of the Sun, divides itself into two distinct central regions. One is nearly black, while the other basks in tt whitish light reflected from the surface of the Earth/’

Collins was struck by the interplay of the three lighting effects on the Moon; the Sun’s corona, the dim light from Earth and the deep black of the star-peppered sky, combining to gently illuminate the lunar surface below’ with a bluish light.

“This cool, magnificent sphere hangs there ominously/’ he wrote in his autobiography, “a formidable presence without sound or motion, issuing us no invitation to invade its domain. Neil sums it up: ‘It’s a view’ worth the price of the trip.’ And somewhat scary too. although no one says that.’’