Earth orbit and TLI

SETTLING INTO ORBIT

In only 11V2 minutes, the Saturn V had accelerated the Apollo spacecraft to nearly eight kilometres per second. The length of the stack had been reduced by two-thirds and the remaining stage, along with the spacecraft, had been lifted to an altitude of between 170 and 185 kilometres above Earth and above the vast majority of the atmosphere, though by no means out of it completely.

It was in orbit and the crew were experiencing weightlessness. They had almost three hours in which to give their ship a thorough checkout before setting off for the Moon with an engine burn called transhmar injection (TLI), and no one was keen to ignite it unless they knew it would be sending a good ship. In that time, they would make not quite two orbits of Earth although, if required, there was a contingency for an extra orbit.

|

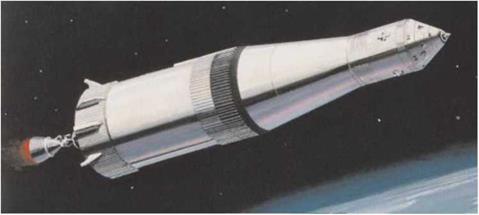

Artist’s impression of the spacecraft and third stage during the Earth orbit phase. (NASA) " " |

W. D. Woods, How Apollo Flew to the Moon, Springer Praxis Books,

DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7179-1 4. © Springer Science+Business Media. LLC 2011

As soon as the J-2 engine at the rear end of the S-IVB third stage had shut down, a pair of Liny auxiliary rocket engines at the base of the stage’s outer skin burned for a minute or so in an effort to keep the propellants settled at the bottom of their tanks. Other small manoeuvring engines began to operate to ensure that the stage would always point in the direction of travel with the spacecraft’s optical systems facing the stars. Once everything had settled down, a pair of aft-facing valves were opened to allow; hydrogen gas from the S-IVB‘s supercold fuel tank to safely vent to space as heat leaked in and caused the fuel to boil. This venting acted like a very weak rocket thruster and provided a Liny propulsive force that continued to keep the propellants settled at the bottom of their tanks long after the auxiliary thrusters had stopped.

Microgravity

Weightlessness is the common term for what is usually known in the space industry as microgravity though it is arguable which is the more accurate term. Microgravity implies a virtual lack of gravity which reinforces a common misconception that space is notable for the absence of this universal force. At the altitude the spacecraft was coasting, the force of Earth’s gravity was almost as much as it was down on the surface, yet the crew and all the loose objects in the cabin w’ere floating.

The body reacts to microgravity in ways that are now quite well understood. But when Apollo began to fly. no one had been in space for more than two weeks, and that had been in a claustrophobic Gemini cabin. After their Apollo 16 flight, veteran astronaut John Young and rookie Charlie Duke described their reactions to it. “It’s really neat; beats work," was Young’s opinion. Duke noticed how, with the cardiovascular system no longer having to work against gravity, the body’s fluids tended to go Low-ards the head. "For the first rest period, I had that fullness in the head that a lot of people have experienced. More of a pulsing in the temples, really than a fullness in the head.” Young had attempted to anticipate the effects. "I tried to outguess it by standing on my head for five minutes a night a couple of weeks before launch. Standing on your head is a heck of a lot harder."

Like a lot of crewmen, and taking note of the nausea experienced during earlier flights. Alan Bean took his time when he moved around the cabin at first. "I think we were all pretty careful and I had the feeling that if I had moved around a lot. I could have gotten dizzy. But I never did. Everyone was pretty careful and after about a day. it didn’t make any difference. We were doing anything we wanted." Bean also noted the way fluids gathered in the head: ‘ Your head shape changes. I looked over at Dick [Gordon] and Pete [Conrad] about two hours after insertion [into Earth orbit] and their heads looked as if they had gained about 20 pounds.”