The monster flies

Up to the moment of launch, the entire weight of the space vehicle had been resting on four hold-down arms mounted around the edge of a 14-metre hole in the launch platform through which the engines could belch their fire down onto the deflector. These arms included strong pincers with mechanical linkages that firmly held the base of the first stage to the platform against the thrust of the engines. When the computers that controlled the launch had decided that all the engines were up to full thrust, the four hold-down arms were opened by their linkages being pneumatically collapsed. Simultaneously, three small tail service masts that had supplied fuel and other services to the bottom of the S-IC disconnected and swung upwards. Protective hoods, some actuated by cords attached to the rocket itself, fell over both the arms and masts before the vehicle rose enough to subject them to the full blast of its exhaust.

Up to the moment of launch, the entire weight of the space vehicle had been resting on four hold-down arms mounted around the edge of a 14-metre hole in the launch platform through which the engines could belch their fire down onto the deflector. These arms included strong pincers with mechanical linkages that firmly held the base of the first stage to the platform against the thrust of the engines. When the computers that controlled the launch had decided that all the engines were up to full thrust, the four hold-down arms were opened by their linkages being pneumatically collapsed. Simultaneously, three small tail service masts that had supplied fuel and other services to the bottom of the S-IC disconnected and swung upwards. Protective hoods, some actuated by cords attached to the rocket itself, fell over both the arms and masts before the vehicle rose enough to subject them to the full blast of its exhaust.

The release of the Saturn V was not instantaneous: it was once described as more of an ooze-off rather than lift-off. This was in part due to a number of tapered pins mounted to the hold-down arms, which were pulled through dies affixed to the bottom of the S-IC.

This controlled release mechanism limited the acceleration of the rocket for the first 15 centimetres of its ascent.

|

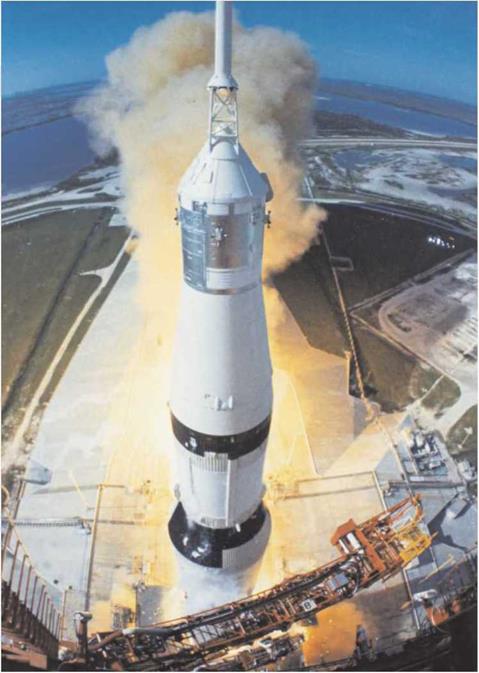

Apollo 15 begins its ascent from Pad 39A as the swing arms retract. (NASA) |

As soon as the immensely heavy vehicle began to rise, it could not safely return to the pad, so for the first 30 seconds of flight, intentional shutdown of the engines was explicitly inhibited. In reaction to this change in circumstances, five access arms that had continued to service the vehicle up to the moment of launch now had to quickly swing clear, their motion triggered by the first two centimetres of travel. As part of that action, all the umbilicals connected to the vehicle had to drop away, and their disconnection marked the starting point for the first of seven ‘timebases’ which orchestrated the control of the Saturn V. Timebase 1 would operate through most of the first-stage burn.

As 3,000 tonnes of metal and volatile propellant rose past the umbilical tower, it could be seen to lean disconcertingly to one side as though it were about to go out of

control. This was an entirely planned yaw rotation designed to manoeuvre the rocket away from the launch tower as a precaution against a failed swing arm or a gust of wind that might push the vehicle back towards the unyielding tower.

control. This was an entirely planned yaw rotation designed to manoeuvre the rocket away from the launch tower as a precaution against a failed swing arm or a gust of wind that might push the vehicle back towards the unyielding tower.

It took about 10 seconds for the entire length of the space vehicle to clear the tower, at which point responsibility for the mission passed from the Launch Control Center in Florida to the Mission Operations Control Room (MOCR) on the outskirts of Houston, Texas.

Twenty seconds after lift-off, the four outboard engines canted away from the vehicle’s centreline so that if one of them were to fail, the thrust of the others would be directed to act nearer to its centre of mass and thereby improve the chances of the instrument unit continuing to steer the rocket successfully.

The first two minutes of the Saturn V’s flight was a spectacular affair attracting many hundreds of thousands of sightseers to the roads and beaches around KSC to witness each launch. Over a million people are believed to have gathered for the launch of Apollo 11. At Apollo 4’s lift-off, which was the first time a Saturn V had flown, TV presenter

Walter Cronkite was bemused to find pieces of the ceiling coming down around him as the roar from the five F-l engines shook the temporary CBS studio from five kilometres away as millions of viewers looked on. Until then, few had appreciated the intensity of sound from five of these engines in free air. Once the acoustic energy finally reached them, people described how they didn’t so much hear the rocket as feel it. The slow’ rate of this leviathan’s majestic rise only served to lengthen its assault on the human body.