The crew arrive

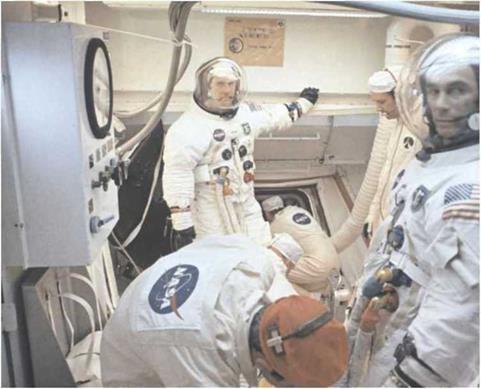

After a hearty but low-residue breakfast in the crew quarters located some kilometres south of the VAB, the prime crew walked into the suiting-up room where a covey of technicians helped them to don the spacesuits which would protect them if the cabin unexpectedly depressurised early in the mission. Careful checks were made to ensure that the suits were airtight (checking the pressure integrity in NASA parlance) before the crew were finally sealed in, drawing on a portable supply of oxygen which they would carry with them to the launch pad.

The reason for sealing the crew inside their suits so early was linked to the fire in the Apollo 1 spacecraft. In its aftermath, it was decided that the cabin would have a mixed atmosphere of nitrogen and oxygen prior to launch, to make the interior much less flammable. After launch, as the vehicle ascended and the outside air pressure diminished, the cabin atmosphere was allowed to vent overboard and be replaced by pure oxygen from the spacecraft’s tanks. As it did so, automatic systems ensured that adequate cabin pressure was maintained, never going below about one-third of the atmospheric pressure at sea level. In the space of several minutes, the pressure in the suits also dropped by two-thirds, and without preparation this could cause nitrogen in a man’s bloodstream to come out of solution and give him the ‘bends’ – a problem also faced by divers who rise too rapidly through a column of water. To avoid this condition, nitrogen was flushed out of the crew’s bodies by having them breathe pure oxygen for several hours prior to lift-off while sealed in their suits.

Three hours before launch, the crew arrived at the 320-foot level of the launch umbilical tower and walked along the highest of the nine access arms, nearly 100 metres above the launch platform. This arm led into the so-called ‘white room’, a controlled environment high above the Florida sands that gave access to the command module’s hatch. One by one they entered the cramped confines of the CM aided by the pad crew who strapped them tightly into their couches and changed their oxygen supplies from the portable kit to the spacecraft’s circuit.

The commander entered first and settled into the left couch from where he would be able to scan the instruments and watch for any issues affecting their trajectory. If trouble arose that threatened the crew, he would abort the mission by twisting the

|

The Apollo 16 crew carry their portable oxygen supplies on their way to the launch pad. (NASA) " |

translation control with his left hand. From Apollo 11 onwards, he had the option of flying the Saturn to orbit manually if the rocket’s guidance system failed, guided by the instruments in front of him. Normally the lunar module pilot (LMP) entered next, taking the right couch. In this position he could watch over the spacecraft’s systems. The command module pilot (CMP) entered last to occupy the centre couch. During ascent, his major role was to assist the commander in monitoring the progress of their climb and to operate the computer.

There was only one exception to this arrangement when Mike Collins, CMP on Apollo 11, took the right seat and entered before Buzz Aldrin, who was LMP. Collins felt that the start of the elevator ride at the bottom of the launch umbilical tower was really the start of his journey to the Moon. Walking across the ninth arm, he was impressed at the contrasts in his field of view. "On my left is an unimpeded view of the beach below, unmarred by human totems; on my right, the most colossal pile of machinery ever assembled.’1 By the time Collins was named with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin as the prime crew of Apollo 11, his crewmates had already served as backup crew on Apollo 8 and had practised launch procedures

|

The white room at the end of the ‘320-foot’ swing arm. It is being held to the hatch of the Apollo 11 command module. (NASA) |

with Buzz in the centre couch. It was decided not to change this, and so Collins trained for the right seat at launch.

In the confined space of the white room, Collins continued a space age tradition by giving the leader of the pad team, Guenter Wendt, a going-away gift; in this case, a tiny trout nailed to a plaque in recognition of Wendt’s tall fishing tales. There were often little gifts or pranks that helped to lift the tension in the edgy moments before a crew were shut inside the spacecraft. Armstrong gave Wendt a ticket for a ‘space taxi ride’ and Aldrin presented him with a Bible. In return, the German gave Armstrong a mock ‘Key to the Moon’. As the Apollo 14 crew were boarding, Alan Shepard, then the oldest of the active astronauts and already a grandfather, presented Wendt with a Second World War German Army helmet, and took receipt of a mock walking stick dubbed the ‘lunar explorer support equipment’.

|

Tom Stafford and Gene Cernan in the white room as they wait to enter the Apollo 10 command module. (NASA) |

When the cabin was sealed, the pad team retired to a safe distance and the swing arm was rotated 12 degrees away, to place the white room close alongside, ready to be returned should an emergency arise that required the crew to exit the spacecraft. At this early stage, the crew kept themselves occupied with checks of their ship and worked with the spacecraft test conductor at the local control centre to examine as many vital systems as possible. Communications were tested – in particular a special circuit set aside for calling an abort to the mission. Tanks for the service module’s four sets of little manoeuvring thrusters, the reaction control system (RCS), were pressurised to force propellant towards the thrusters and enable them to work. The guidance system was initialised; the spacecraft would not direct the rocket but it had to know where it was and it needed to keep track of where the Saturn V was taking it in case the commander had to assume control. Then with five minutes remaining in the countdown, the arm carrying the white room was swung away from its interim position around to the opposite side of the launch tower, to position it as far away as possible from the plume of flame that the rocket would leave in its wake as it lifted off.

|

Guenter Wendt presents Alan Shepard with a walking stick before Apollo 14. (NASA) |