EXPLORATION AT ITS GREATEST: APOLLO 15

The final three flights of the programme took Apollo to new and worthy heights of exploration, science and discovery. Since the engineering had been largely proved, science became the driving force behind the choice of landing site and the equipment to be carried. Both the LM and CSM were upgraded to carry more supplies and

|

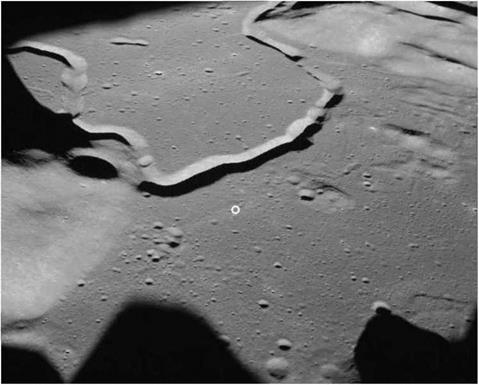

The Apollo 15 landing site (circled) next to the 1.5-km-wide Hadley Rille. (NASA) |

increase their endurance. To further facilitate this final push for knowledge, a small fold-up electric car was carried on the side of the lunar module and a suite of sensors and cameras were fitted into an empty bay of the service module. The capabilities of the Apollo system were pushed ever further by extending the J-missions to 12 days.

Scenically, Apollo 15 had everything. Its target was an embayment of a lunar plain bounded by the stunning mountains of the Apennine range and a meandering channel called Hadley Rille. It was well north of the equatorial band to which Apollo had heretofore been restricted, but the relaxation of operational constraints made such a mission viable. It was an enchanting site for exploration, where the story of the Moon’s most ancient time began to be revealed.

Apollo 15’s launch from Earth on 26 July 1971, while as spectacular as any, gave no surprises. The coast to the Moon was punctuated by a fault in the main engine’s control circuits and a leak in the CM’s water supply, both of which were dealt with successfully. Once they had landed at Hadley Base, the crew of the LM Falcon, David Scott and Jim Irwin, depressurised the cabin to allow Scott to survey the site by poking his head out of the top hatch of the lander. The following three days saw the two explorers carry out a relentless programme of exploration that sampled the rocks of both the mare beneath them and the adjacent mountains beside them. A

ground-controlled TV camera on their rover allowed their audience to accompany them as they visited landscapes that Capcom Joe Allen described as "absolutely unearthly”. The presence of the rover changed the rules of lunar exploration. Instead of working near the LM for the first part of a moon- walk, then going on an excursion, a rover-equipped crew jumped on board and made tracks as soon as they could so that, if it failed, they would have adequate reserves of oxygen to walk back to the safety of the LM.

Their first excursion took them on a drive to where Hadley Rille ran below Mount Hadley Delta. Scott said the vehicle was somewhat sporty to drive, but both crewmen benefited from the rest gained while driving between stops. Upon their return, they set up a third ALSEP science station and in trying to emplace sensors for a heat-flow experiment Scott had difficulty in drilling into the lunar soil. Although the material was an unconsolidated mass of powder and debris, over a period of billions of years it had become so compacted as to be as hard as rock. The drill had to be redesigned for the next mission.

Their first excursion took them on a drive to where Hadley Rille ran below Mount Hadley Delta. Scott said the vehicle was somewhat sporty to drive, but both crewmen benefited from the rest gained while driving between stops. Upon their return, they set up a third ALSEP science station and in trying to emplace sensors for a heat-flow experiment Scott had difficulty in drilling into the lunar soil. Although the material was an unconsolidated mass of powder and debris, over a period of billions of years it had become so compacted as to be as hard as rock. The drill had to be redesigned for the next mission.

In their second excursion they drove up the lower slopes of Mount Hadley Delta, where they hoped to find fragments of the original lunar crust. Near a fresh crater they collected a likely candidate which the press instantly dubbed the ‘Genesis Rock’ because scientists said they hoped the sample would yield insight into the Moon’s earliest era. Back at the LM, Scott battled once more with the balky drill. Although he managed to obtain a core that was more than two metres long, he found he could not pull it out of the ground. With the surface mission far behind the planned timeline, the third moonwalk was shortened. On their final outing, and with Irwin’s help, Scott managed finally to extract the deep core. Then they drove to the edge of Hadley Rille where they could see layers of lava exposed in the opposite wall. As a final flourish, this time in the name of science rather than golf, Scott carried out a simple experiment in which he simultaneously dropped a hammer and a falcon feather in order to prove the theories of Galileo and demonstrate that objects of differing mass fall at the same speed in the absence of air.

While the surface crew redefined lunar surface exploration at Hadley Base, Alfred Worden operated the apparatus built into CSM Endeavour. As it orbited the Moon, large swathes of terrain were photographed with modified reconnaissance cameras, and the surface was surveyed with instruments that could determine the composition of the lunar material. A laser altimeter measured the varying elevation of the ground passing beneath, obtaining data which quickly demonstrated the relationship between the highlands and lowlands and, along with how their composition differed, insight into the Moon’s history. Before departing for Earth, the crew deployed a

subsatellite that reported measurements of the Moon’s environment for seven months.

The knowledge gained from Apollo was beginning to tell a story of an ocean of molten rock whose surface cooled to form an aluminium-rich crust. This was then punctured by massive asteroid impacts whose wounds were later filled in as iron-rich lava welled up through deep fractures, ft was a story that would also tell of Earth’s earliest years.