THE SUCCESSFUL FAILURE: APOLLO 13

Now that NASA knew how to land accurately on the Moon, it could pursue its science goals with increased vigour with a view to finding out how the Moon formed

although whether the tax-paying American public wanted to know this information is a moot point. Lunar studies before Apollo had focused upon one large feature as perhaps being a key to understanding much of the visible lunar landscape. This was Mare Imbrium. a lunar ‘sea’ that is readily visible from Earth. In reality, it is a vast circular structure, fully 1,300 kilometres in diameter, that was formed by the impact of an asteroid early in lunar history. The resultant depression was subsequently filled with dark lava. Like any impact structure, the Imbrium Basin would have been surrounded by a blanket of material ejected during its formation. The cadre of lunar scientists involved in Apollo believed that much could he learned by sampling this ejecta blanket, which appeared to dominate the near side. To sample it, they proposed a landing site for Apollo 13 in hummocky terrain just north of the crater Fra Mauro, and Apollo 12 took pictures to assist in planning.

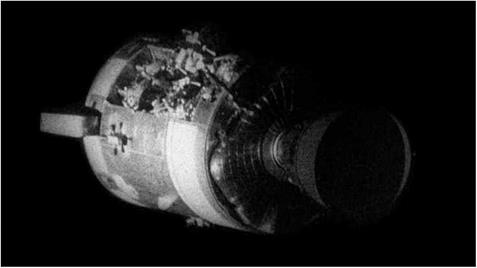

Apollo 13’s first problem occurred several days before its 11 April 1970 launch, when command module pilot Ken Mattingly had to be replaced by his backup. Jack Swigcrt, owing to a possible exposure to rubella. The glitches continued soon after launch when one of the five engines in the second stage of the Saturn V shut down prematurely. However, these issues were as nothing compared to what occurred almost 56 hours into the mission. When Swigert operated fans to stir the contents of an oxygen tank in response to a request from mission control, the tank violently burst. The resultant shock blew out one of the skin panels of Odyssey’s service module and damaged its oxygen system sufficiently to cause most of the spacecraft’s supply of this vital gas to leak out to space. At that time, Apollo 13 was.328,300 kilometres from Earth and 90 per cent of the way to the Moon.

This traumatic event deprived the spacecraft of electrical power and began a four- day feat of dedication, ingenuity and endurance by the crew, the flight control team and thousands of support staff to effect a safe return to Earth. Every system in the SM was rendered inoperable by the blast itself, by the lack of power, or by concern that it may have been damaged and represented part of the problem rather than part of the solution. The CM had to be powered down very quickly to save its remaining consumables, as they would be needed for re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere. This left the LM Aquarius as the only means of sustaining the crew while the two joined ships flew7 around the Moon for a slingshot back to Earth. It also became the sole means of manoeuvring to speed up the return trajectory and control the accuracy of its arrival.

Without power, the interior of the spacecraft soon cooled to around 6 C. In these uncomfortably low temperatures, the crew grew increasingly exhausted as they took refuge in the LM while nursing their dead CSM to the safety of Earth, its command module being the only way to pass through the atmosphere. During the long fall to Earth, they had to construct devices to remove toxic carbon dioxide from their air, w ork through complex checklists to fire the LM’s main engine, and also improvise a means of firing it for the correct duration while ensuring that it was correctly pointed. They found themselves carrying out difficult and often completely new procedures without having slept for days.

In the flight’s final moments on 17 April as it re-entered Earth’s atmosphere, the world was gripped by the tension of not knowing whether Odyssey’s heatshield had been damaged by the blast. A safe splashdown in the Pacific Ocean ended a failed

|

|

|

mission that became perhaps the finest hour for a spacecraft’s crew, its ground control team and their supporting organisations. It showed that in spaceflight, and in the face of terrible odds, toughness and competence could win through.

Despite the superstition that surrounds the flight number, and knowing with hindsight that the spacecraft left tiarih with a flaw on board. Apollo 13‘s oxygen tank rupture occurred at just about the most opportune time. Much earlier and their coast to the Moon and back would have been too long for the LM to sustain them. Much later, and they might not have had a LM available to act as a lifeboat. In fact, it was a case of lucky 13.