LIGHTNING STRIKES: APOLLO 12

By concentrating almost single-mindedly on the goal of a manned lunar landing, secondary considerations like landing accuracy and science had taken a back seat. In the event. Apollo 11 had landed about seven kilometres beyond its planned site and for some time, no one knew exactly where they were. Not even Mike Collins had been able to see Eagle through his sextant – a powerful optical instrument built into Columbia’s hull. The science payload had been severely limited by mass constraints and lack of time. Future missions would make amends because the United States had invested heavily in the infrastructure to support Apollo and wanted to see results. It also demanded justification for the continuing costs. Fittingly, science became that justification.

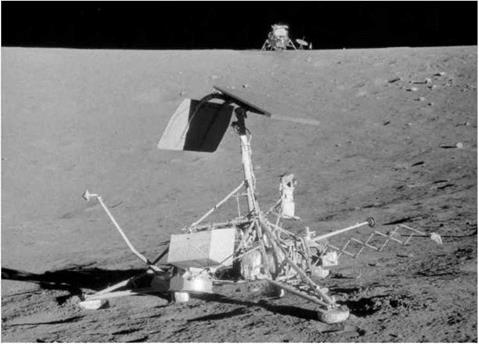

To gain knowledge from the Moon. NASA had to go to sites where Earth-based and orbital imagery suggested that answers to questions might lie. However, given the limited walking range of an astronaut on the lunar surface, the ability to land "on target’ became paramount. Although Apollo 12 was not sent anywhere of particular geological importance, it was given a very small target to aim for. Specifically, it was to land within walking distance of Surveyor 3. a small robotic lander that NASA had sent to Occanus Procellar urn in April 1967.

The mission courted disaster in its first minute when the vehicle flew through a rain cloud and invoked a lightning strike. Regardless, the crew’ continued to the Moon amid fears that their command module may have been damaged by the surge of power that had passed through it. In the event, the CSM Yankee Clipper proved to be unharmed, and on 24 November 1969 Charles ‘Pete’ Conrad and Alan Bean landed their LM Intrepid some 1.500 kilometres west of where Eagle had landed and a mere 200 metres from Surveyor 3. This demonstrated that ground controllers and crew could bring a lunar module down exactly where they wished. Richard Gordon, orbiting overhead, confirmed their position by spotting both the LM and the Surveyor on the surface through his sextant.

Since Apollo 12 was an II-mission, Conrad and Bean made two moonwalks. On the first they laid out an ALSEP which was an autonomous scientific station that operated on the lunar surface for many years after they left. The next day they hustled across the surface taking a circular route of over a kilometre, pausing at preplanned points of interest on the way to visit the Surveyor probe. After examining

|

The unmanned spacecraft. Surveyor 3, with the Apollo 12 LM Intrepid beyond. (NASA) |

and photographing the probe, they removed pieces to enable researchers to study how well the hardware had survived 31 months of exposure to the lunar environment. In terms of public relations, the low point for this fun-loving crew was when their television camera was ruined early in the first moonwalk by being inadvertently pointed at the Sun. TV networks struggled to provide a visual accompaniment to the crew’s voice communication and audiences quickly became bored of listening to indistinct and often arcane yakking by the two guys on the surface. Nonetheless, like every crew after them, Conrad’s and Bean’s two joyous forays out on the surface yielded samples of greater bulk than the previous mission, and the scientists were more than happy with what they brought back. In particular, tiny grains of a very slightly radioactive rock type began to lift the lid on important aspects of the Moon’s early history.

Despite concern that it may have been damaged during launch, Yankee Clipper’s successful splashdown concluded a successful, if charmed 10-day mission that was marred only by the loss of the TV coverage.