TASK ACCOMPLISHED: APOLLO 11

Apollo 11 departed the Kennedy Space Center in the early morning of 16 July 1969 on a mission that would culminate in an attempt to land on the lunar surface. It is widely quoted that over a million people gathered in the vicinity of Cape Canaveral to witness the start of what promised to be a defining event in human history. For the first four days, its crew of Neil Armstrong as commander, lunar module pilot Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin and the command module pilot Michael Collins followed a path

|

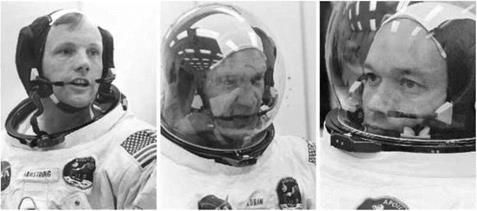

The Apollo 11 crew during suiting-up operations before their flight. Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins. (NASA) |

blazed by their predecessors. They even took time out to give viewers to the TV networks an extended tour of their lunar module, Eagle, with an improved colour camera.

On the fourth day, Armstrong and Aldrin left the command module, Columbia, in the charge of Collins, undocked, and fired Eagle’s descent engine to enter the descent orbit around the Moon. As communications proved to be somewhat troublesome, Armstrong reorientated the LM slightly in order to improve reception. On approaching the point where they were to reignite the engine for the landing phase, Armstrong timed the passage of landmarks to determine whether their trajectory was as it should be, and saw that they seemed to be a little ahead. The engine was ignited on time, and after several minutes of continuing to monitor the passage of the landscape below they rotated the LM to allow its radar to take altitude and velocity measurements.

At this point, things became hair-raising, especially for the flight controllers in Houston who lacked the crew’s situational awareness. Thanks to a subtle flaw in the spacecraft’s electronic systems, the computer began to complain of being overloaded, ft displayed debugging codes that were never meant to be seen during a flight and which most people at mission control, as well as the two men in the spacecraft, had little knowledge of. However, just two weeks before the mission, the LM computer experts had studied a large number of such codes, including those that the crew were seeing. Given that the vehicle was otherwise operating normally, they recommended that the descent continue.

Armstrong was able to monitor where on the lunar landscape the computer was guiding them as Aldrin read out relevant numbers. When he saw that their destination appeared to be a boulder field near a large crater, he put himself in the control loop earlier than planned, and manoeuvred to smoother ground 300 metres further along the flight path. Meanwhile, mission control began to worry about a shortage of propellant. When only 15 seconds remained before mission control would have advised the crew to abort the landing attempt, Eagle successfully realised John F. Kennedy’s goal on 20 July 1969 by touching down in the southwest comer of Mare Tranquillitatis.

In the minds of the crew the difficult part of Apollo’s goal had been achieved, yet the public was more eager to witness an event whose scale was much more human and personal. This was the moment when a man made a boot impression in the lunar dust. Armstrong later pointed out that the moonwalk carried far fewer dangers than manoeuvring seven tonnes of flimsy spacecraft loaded with explosive propellants down onto an unknown rocky surface on the end of a rocket flame, while surrounded by a hard vacuum. Nonetheless, it was inconceivable that a crew would land on the Moon and not walk on the surface!

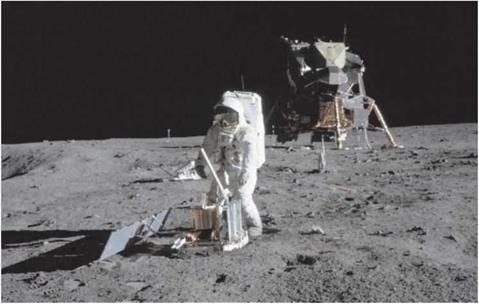

Over the subsequent hours, in one of the most memorable television events in human history, Armstrong and then Aldrin descended the ladder onto the lunar surface. Observed by a black-and-white television camera whose mode of operation gave them a ghostly appearance, they took photographs, collected samples and set up three simple scientific experiments: a small seismometer, a laser reflector and a solar wind collector. The social significance was not forgotten when the flag of the United States was raised on behalf of the nation that had paid for the venture. Additionally, a plaque was unveiled to inform any future visitors to Tranquillity Base that its first visitors "came in peace for all mankind” and the two explorers took a telephone call from President Richard Nixon. After 2 V2 hours, the moonwalk ended. Armstrong and Aldrin took their exposed film and a box of lunar samples up to the ascent stage, repressurised the cabin and tried to get some fitful sleep before

|

Buzz Aldrin deploys a seismometer at Tranquillity Base on Apollo 11. (NASA) |

performing lift-off for the second time in less than a week. Their return to Collins in Columbia and the trip back to Earth were uneventful, concluding with a landing in the Pacific Ocean on 24 July.

The Apollo programme had been designed to be aggressive from the outset, with launch facilities at KSC constructed for multiple or closely spaced launches. Now, with the moonlanding successfully accomplished, and America’s spending on the Vietnam War draining the nation’s purse, the scale of lunar exploration was cut back by Congress. Nevertheless, the sheer momentum of the programme brought another landing attempt only four months later.