GUTSY DECISIONS: APOLLO 8

Even before Apollo 7 was launched, managers were dreaming up something special for Apollo 8: an audacious six-day flight to the Moon in a hastily arranged mission which turned an otherwise unfavourable set of circumstances into a blessing.

Apollo 8 had originally been planned as the D-mission, a test of the entire Apollo system including a lunar module in low Earth orbit, on the assumption that Apollo 7 would successfully carry out the C-mission. However, the first man-capable LM was not ready for flight owing to a litany of problems: stress fractures had appeared in some of its structural components; the type of wiring used on the intended spacecraft

|

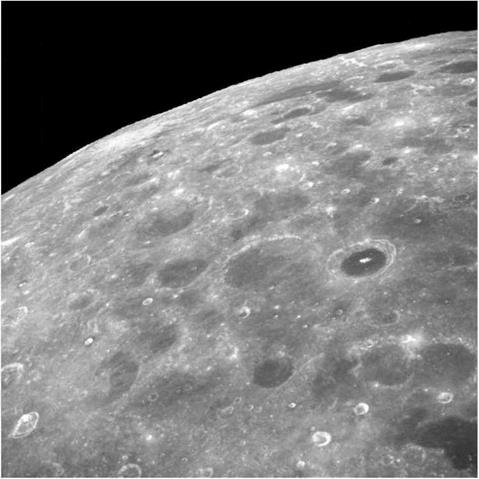

The Moon’s far side, photographed from Apollo 8 after it departed for Earth. The distinctive dark-floored crater is Jenner, 71 kilometres in diameter. (NASA) |

was prone to breakage; and the engine for the ascent stage was prone to combustion instability. Bereft of a LM, managers were unwilling simply to repeat Apollo 7, so they altered the mission sequence and brought the deep-space goals of the E-mission forward, but without a lander.

Furthermore, they took the gutsy decision to send the CSM all the way to the Moon and place it into lunar orbit. Although this would fulfil some of the goals of the E-mission (deep-space tracking, deep-space thermal control, lunar navigation), the fact that it would be a CSM-only flight prompted NASA to label it the C-prime – mission. Although it would provide operational experience needed to manage lunar missions, its unstated purpose was to reach the vicinity of the Moon before the Soviet Union. Intelligence reports suggested that the Soviets were preparing to send a crew on a flight that would loop around the back of the Moon and head straight

back to Earth, and the propaganda value of such a circumlunar mission would be immense. On the other hand, if the Americans could get there first, and enter orbit around the Moon, they could claim to have essentially won the space race as long as the Soviets did not achieve a landing.

On the morning of 21 December 1968 Frank Borman, Bill Anders and Jim Lovell rode a Saturn V away from Earth to become the first people to swap the Earth’s gravitational hold for that of another world. The three-day long coast out to the Moon gave Jim Lovell plenty of time to practise monitoring the ship’s trajectory by taking sightings of Earth, the Moon and the stars. On 24 December 1968, Apollo 8 took its crew around the lunar far side where they fired its SPS engine to enter lunar orbit to begin 10 revolutions, each lasting two hours. As they coasted 110 kilometres above the cratered surface, the crew closely examined two sites that were being considered for the first landing and, along with tracking stations on Earth, practised techniques for navigating while orbiting the Moon. Much of Earth’s population with access to television watched with amazement when the crew made an extraordinary Christmas-time black-and-white television broadcast made on the penultimate orbit, during which they read the first few verses from the Bible’s Book of Genesis while the stark early morning landscape of the Moon passed in front of the camera.

On the morning of 21 December 1968 Frank Borman, Bill Anders and Jim Lovell rode a Saturn V away from Earth to become the first people to swap the Earth’s gravitational hold for that of another world. The three-day long coast out to the Moon gave Jim Lovell plenty of time to practise monitoring the ship’s trajectory by taking sightings of Earth, the Moon and the stars. On 24 December 1968, Apollo 8 took its crew around the lunar far side where they fired its SPS engine to enter lunar orbit to begin 10 revolutions, each lasting two hours. As they coasted 110 kilometres above the cratered surface, the crew closely examined two sites that were being considered for the first landing and, along with tracking stations on Earth, practised techniques for navigating while orbiting the Moon. Much of Earth’s population with access to television watched with amazement when the crew made an extraordinary Christmas-time black-and-white television broadcast made on the penultimate orbit, during which they read the first few verses from the Bible’s Book of Genesis while the stark early morning landscape of the Moon passed in front of the camera.

If their burn to enter lunar orbit had failed, the crew would have simply slingshot around the Moon and returned to Earth with little intervention – just as the Soviets intended to do – but the burn had been performed successfully and the spacecraft had entered orbit. It was Apollo 8’s next manoeuvre that really scared the managers. Although the SPS engine had been designed for reliability, everyone was aware that its failure would doom the crew to stay forever in the Moon’s grasp. Worse, because the engine bum would take place around the Moon’s far side, no one on Earth would be able to monitor its progress, and instead would have to wait until the spacecraft re-emerged, hopefully on a path for home. Shortly after midnight in Houston, Texas, on Christmas Day, Apollo 8 reappeared around the Moon’s eastern limb exactly on time, with Jim Lovell’s playful words to mission control, "Please be informed, there is a Santa Claus.”

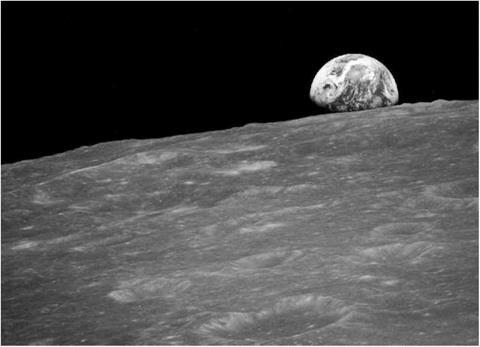

Apollo 8’s voyage to the Moon raised the morale of the many thousands who were working brutally long hours to achieve the landing goal, and by allowing navigation, thermal control and communication procedures to be tested it gave NASA the operational experience it needed to make future lunar trips. On a philosophical level, the flight gave the human race its first glimpse of its home planet as seen from another world. In addition to television views of Earth from a vantage

|

The first image of Earthrise taken by a human. Bill Anders’s Apollo 8 photograph was taken a few seconds before more famous colour images were snapped. (NASA) |

point between the two worlds, while orbiting the Moon the awed astronauts photographed their home planet rising over a barren lunar horizon. These photographs would later become a catalyst for the rise of the environmental movement and were true icons of the age.