WHICH WAY?

Even as Kennedy announced that the Moon would be the destination for America s aerospace community, managers still had to decide how to make the trip. At first, two competing methods, or modes, were investigated, both of which had powerful advocates and detractors. A third plan struggled for attention and was often mocked.

The first plan was known as direct ascent. Although it appeared at first glance to be the simplest solution, it was the most audacious of all. It entailed the development of a truly monumental booster that could hurl a large spacecraft directly to the Moon without pausing in Earth orbit. This Apollo ship would carry everything needed to complete the mission and get back home; landing gear, supplies for the trip and for the lunar surface, and engines to lower the entire vehicle to the Moon and then lift off again for the journey home. The proponents of this brute-force method said it was the simplest and easiest proposal to realise within the time allowed, avoiding complexity where possible. But on the minus side, it would have required the development of the Nova, a rocket of simply stupendous proportions to execute – one that would have dwarfed even the mighty Saturn V that was eventually built. For a time, the direct mode was championed by Robert Gilruth, leader of the Space Task Group, which was a small organisation within NASA that included Faget and Maynard and which would go on to form the core of the Manned Spacecraft Center, now known as the Johnson Space Center, in Houston.

The charismatic German rocket engineer Wernher von Braun – the director of the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama – had different ideas. He and his team had been brought to the United States after the war and had helped the US Army to develop its first useful rockets. They then formed part of an effort to create a family of large launch vehicles collectively known as Saturn. While some at Marshall welcomed direct ascent and the Nova, von Braun preferred Earth orbit rendezvous (EOR), believing it to be more readily attainable. This called for a sequence of the smaller Saturn vehicles to place the components of the ship into Earth orbit where they would be assembled for the flight to the Moon. When the launch facilities Wernher von Braun beside an early Saturn at Merritt Island near Cape Canaveral launch vehicle. (NASA) were being laid out by von Braun’s

The charismatic German rocket engineer Wernher von Braun – the director of the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama – had different ideas. He and his team had been brought to the United States after the war and had helped the US Army to develop its first useful rockets. They then formed part of an effort to create a family of large launch vehicles collectively known as Saturn. While some at Marshall welcomed direct ascent and the Nova, von Braun preferred Earth orbit rendezvous (EOR), believing it to be more readily attainable. This called for a sequence of the smaller Saturn vehicles to place the components of the ship into Earth orbit where they would be assembled for the flight to the Moon. When the launch facilities Wernher von Braun beside an early Saturn at Merritt Island near Cape Canaveral launch vehicle. (NASA) were being laid out by von Braun’s

compatriot Kurt Debus, EOR appeared to be the best way to achieve the lunar goal. The perceived need for launches to occur in quick succession, and the associated processing of the launch vehicles, defined the layout of the new Moon port. In the event, these capabilities would barely be brought to full use.

As engineers and designers studied the options, huge problems became evident in both of these mission modes, and these shortcomings threatened to slip the success of the project past the deadline set by President Kennedy. A major headache was the sheer size of the Nova rocket. Building, transporting, fuelling and finally launching such a gargantuan rocket was becoming difficult to comprehend. One engineer put it in plainer terms: "It would have damn near sunk Merritt Island.” Contractors had to make a start on building the launch facilities, and the type of launch vehicle would be crucial to the layout. One of the larger Saturn derivatives on the drawing board, the C-5, itself around 36 storeys tall, seemed to be a much more sensible solution. This vehicle was later renamed Saturn V, pronounced as ‘Saturn Five’.

Both direct ascent and EOR envisaged sending a single large Apollo spacecraft to the Moon, and its shape and layout were proving to be an equal headache. Seated in a heavy conical Apollo command module mounted at the top of a huge rocket – powered landing stage, the crew would find that all their windows looked towards the sky when, like all pilots, they would rather look down at their approaching landing site. It slowly dawned on the potential astronauts that the CM’s shape could hardly have been less suited to a lunar landing.

At this time, Gilruth’s Space Task Group was based at NASA’s aeronautical centre in Langley, Virginia. Another research group at Langley, who were studying possible trajectories to the Moon, had pointed out the huge weight savings that could be made by using a lunar parking orbit within the mission. In parallel with

|

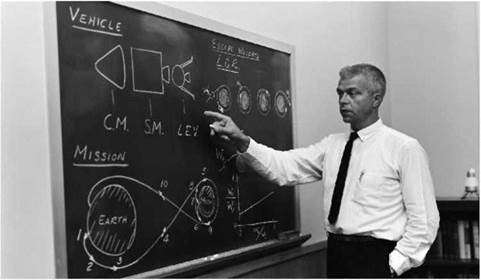

John Houbolt of Langley, the champion of lunar orbit rendezvous. (NASA) |

Lunar orbit rendezvous 11

engineers at Vought Astronautics, they devised a daring but highly efficient means of travelling to the Moon using only a single Saturn C-5 vehicle. It was this third mode that eventually won the day and became America’s path to a new world.