SOYUZ TMA-02M

2011-023A June 7, 2011

2011-023A June 7, 2011

Pad 1, Site 5, Baikonur Cosmodrome, Republic of

Kazakhstan

November 22, 2011

Near the town of Arkalyk, Republic of Kazakhstan Soyuz-FG (R-7) (serial number И15000-037),

Soyuz TMA-M (serial number 702)

167 da 6h 12 min 5 s Eridanus

ISS resident crew transport ISS-28/29 (7S)

Flight crew

VOLKOV, Sergei Alexandrovich, 38, Russian Federation Air Force, Russian, RSA, Soyuz TMA-M commander, ISS-28/29 flight engineer, second mission Previous mission: Soyuz TMA-12/ISS-17 (2008)

FURUKAWA, Satoshi, 47, civilian (Japanese), JAXA, Soyuz TMA-M and ISS-28/29 flight engineer

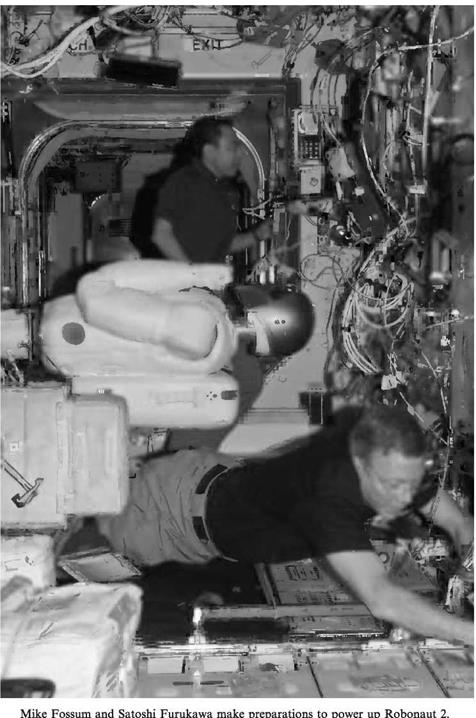

FOSSUM, Michael Edward, 53, NASA, Soyuz TMA-M flight engineer, ISS-28 flight engineer, ISS-29 commander, third mission Previous missions: STS-121 (2006), STS-124 (2008)

Flight log

Flying the second upgraded TMA-M spacecraft into space were another truly international trio, who docked their spacecraft with the Rassvet module on June 9 (June 10, Moscow time). They entered the space station in the early hours of the following day to complete the required safety and update briefings. During the 2-day flight to the space station, the crew had completed the flight development tests begun on Soyuz TMA-M, further qualifying the new vehicle for operational missions.

In the early part of their residency, the three new crew members participated in preparations for the departure of the ATV-2 resupply vehicle from the aft Zvezda port on June 20 and the arrival of Progress M-11M at that same docking location three days later. On June 28, the six crew members had to shelter in their respective Soyuz craft (TMA-21/TMA-02M) as an unidentified piece of orbital debris (designated Object 82618, unknown) passed within just 820 ft (249.93 m) of the station, possibly the closest near miss in the station’s history.

The crew’s experiment program included, in the Russian segment, 725 sessions on 50 experiments, of which 47 were continuations from the previous increments.

|

|

To accomplish this target, there were 359 hours 20 minutes planned for the crew, as well as supportive work during the exchange of crews. There was no dedicated ISS-29 press kit released (instead the kits went from ISS-27/28 to 30/31) to identify research work in the American segment, but it is clear that the work continued without interruption in all sections of the station during this period.

The final Shuttle mission (STS-13 5) arrived at the station on July 10 and remained docked with the station until July 18. On July 12, resident crew members Fossum and Garan donned American EMUs and exited the Quest airlock for a 6h 30min space walk (see STS-135 entry) which was the final space walk of the Shuttle era. On August 1, Volkov accompanied Samokutyaev on a 6h 23 min EVA from the Russian segment (see Soyuz TMA-21 entry).

On August 14, the Zarya module, the first element of the station launched in November 1998, completed 73,000 orbits of Earth.

On September 14, Fossum assumed command of the outpost from Borisenko, ending the ISS-28 phase and commencing the ISS-29 phase. The official end of the outgoing expedition occurred with the undocking of TMA-21 two days later. With the departure of the ISS-28 prime crew, the ISS-29 crew continued as a three – person residence pending the arrival of TMA-22. For the next few weeks, science and maintenance occupied the crew’s time. This included work with Robonaut 2, putting the unit through some at times difficult mobility tests of its hand and neck joints.

On September 29, after a decade of being the only space station in orbit, the ISS was joined by a new neighbor—the Chinese Tiangong-1 (“Heavenly Palace – 1”) mini space module. This was similar to, but slightly smaller than, the early Soviet Salyut space stations launched in the 1970s. A month later, on October 31, the unmanned Shenzhou 8 was launched into orbit on a mission to evaluate the new space station’s docking mechanism. Clearly, a new era of space station operations had begun.

Back on the ISS the science work continued. This trio would be joined by their colleagues when Soyuz TMA-22 docked at the Poisk module on November 16. This was to be a short six-person residency, due to the delays caused by the loss of Progress M-12M the previous August. The first few days of the full crew were a busy time, as the TMA-02M trio prepared to return home. The formal transfer of command from Fossum to Dan Burbank occurred on November 20 and the ISS-29 trio undocked their Soyuz in the early hours of November 22.

The atmospheric burn-up of the discarded modules was captured on video by the station residents as the Descent Module containing the three crew members continued its descent towards Earth. The crew landed safely, although in subzero temperatures. Shortly afterwards, Volkov was flown back to the Cosmonaut Training Center near Moscow and Fossum and Furukawa flew on a NASA jet back to Houston, Texas for postffight readaptation and debriefings.

The crew had spent 166 days on board the station out of the 168 days logged in space. Of these, 97 days were spent as part of the ISS-28 expedition and 67 as prime ISS-29 residents.

Milestones

283rd manned space flight 116th Russian manned space flight 109 th manned Soyuz

2nd manned Soyuz TMA-M and 2nd test flight of the new variant 27th ISS Soyuz mission (7S)

28/29th ISS resident crew

|

Flight crew

FERGUSON, Christopher John, 49, USN Retired, NASA commander, third mission

Previous missions: STS-115 (2006), STS-126 (2008)

HURLEY, Douglas Gerald, 44, USMC, NASA pilot, second mission Previous mission: STS-127 (2009)

MAGNUS, Sandra Hall, 46, civilian, NASA mission specialist 1, third mission Previous missions: STS-112 (2002), STS-126/ISS-18/119 (2008/2009) WALHEIM, Rex Joseph, 48, USAF (Retd.), NASA mission specialist 2, third mission

Previous missions: STS-110 (2002), STS-122 (2008)

Flight log

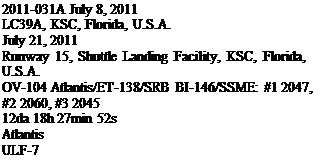

The finale of the 30 yr Space Shuttle program came in July 2011 with the flight of STS-135. This was a mission added to the manifest to utilize the remaining available hardware and was a final opportunity to stock up the station and remove a quantity of unwanted material and trash before finally retiring the fleet.

When Ken Ham and the rest of the STS-132 crew returned in May 2010, discussions were already under way over the possibility of flying one more Atlantis mission. In light of this, Ham called his recent mission “the first last flight of Atlantis” and so it proved. The orbiter had one processing cycle to go through, as rescue orbiter for STS-134—the “first” last Shuttle flight—but once the new flight had been authorized, this became the final processing cycle as, following the STS – 134 mission, the vehicle was processed for STS-135.

Towards the end of 2010, it had become more likely that the mission would indeed fly once the funding had been organized, and by January 2011 the mission was included in the internal flight roster for planning purposes. In February,

|

The final Space Shuttle launch, July 8, 2011. |

NASA management was told that the mission would fly even if adequate funds were not found, but the budget for the mission was authorized in April after saving funds in other areas. By that time, preparations for the mission were well on the way towards completion anyway.

For the final time, the Shuttle ground processing team geared up for a launch. The stacking of the SRBs began towards the end of March 2011, with the ET being attached on April 25. Atlantis was rolled from the OPF across to the YAB on May 16, and by May 18 the stack was completed. The rollout to the pad occurred on the night of May 31/June 1, with the Rafaello MPLM being installed in the payload bay of Atlantis on June 20. The manifest also included a significant number of commemorative items and the U. S. flag that had flown on STS-1, along with a special 9/11 flag. With everything ready for a planned July 8 launch, the July 4 Independence Day weekend was kept free to allow for some extra processing margin. All eyes looked at the weather, which appeared to be the only concern (as it had been so many times) but when NASA affirmed the July 8 launch date, even nature cooperated to see the Shuttle program off in fine style.

Designated ULF-7, the payload included the Raffaello MPLM packed with over 9,0001b (4082.4 kg) of supplies and the Robotic Refueling Mission (RRM) experiment. This was an experiment to demonstrate and test the tools, techniques, and technologies required to develop a robotic satellite-refueling capability, even though the target vehicle might not be designed to be refueled. The astronauts were also to return a failed ammonia pump for evaluation by engineers prior to refurbishment for relaunch at some future date.

After an incident-free launch and ascent to orbit, the crew prepared for the ISS docking by checking the vehicle, inspecting the TPS, and setting up the rendezvous tools and EMUs. Throughout the mission, the crew received well wishes from family, friends, fellow workers, and the general public as the final Shuttle flight continued. Docking with the station occurred on July 10, with the prime ISS resident crew tolling the ship’s bell for an incoming spacecraft one final time for a Shuttle orbiter. One hour and 40 minutes after docking, the hatches were opened and the two crews welcomed each other, followed by the mandatory safety briefings and status updates. The only EVA during the mission would be conducted by the station crew from Quest.

Work began almost immediately, with the RMS used to relocate the 50 ft (80.45 m) external boom to Canadarm2 for the inspection of the Shuttle Thermal Protection System. As the boom was now permanently part of the station, this inspection could not be completed by the crew the day after launch. On July 11, the Raffaello module was transferred to the Harmony Node in a 30 min operation. The supplies included 2,6771b (1,214.28 kg) of food, enough for a full year for the station crews. The crew relocated some of the cargo from Raffaello into PMA-3, with the supplies packed in 17 different racks inside the pressurized logistics module. These included eight Resupply Stowage Platforms (RSP), two Intermediate Stowage Platforms (ISP), six Resupply Stowage Racks (RSR), and one Zero Stowage Rack. An additional 2,2281b (1,010.62 kg) of cargo was stowed on the middeck of Atlantis which also had to be transferred to the station. Sandra Magnus was loadmaster over a planned 130 hours of unloading time during the docked phase. Once empty, the module would be refilled with 5,6661b (2,570.09 kg) of equipment no longer needed on the station, plus discontinued logistics and trash. After an evaluation of available consumables, an extra day was added to the mission to give the crew additional time to relocate all the cargo and supplies between the vehicles.

The EVA from the Quest airlock was performed by ISS astronauts Fossum and Garan on July 12. It lasted 6 hours 3 minutes. The reason for the station crew performing the EVA was essentially one of time and experience. Confirmation that STS-135 would actually launch came late in the cycle, so the training of the crew focused mainly on getting to and from the station and handling the massive cargo transfer. Contingency EVA training was included, but as the astronauts were all Shuttle veterans this made the compressed training cycle much easier to accomplish. The two station resident astronauts, Garan and Fossum, had logged nine previous EVAs between them, three of which were performed together during STS-124 in 2008, so they were used to working together as a team. It was also possible that with so many supplies being delivered, the weight saved from flying no more than four crew members could be reallocated to the logistics manifest.

The objective of this EVA was to retrieve a faulty 1,4001b (635.04 kg) ammonia pump module which had failed in 2010 and had been stowed in the

External Storage Module 2 during STS-133 earlier in the year. The two ISS astronauts relocated it to the cargo bay of Atlantis to be returned and refurbished as a spare unit. They also set up the RRM experiment on an external pallet and released a stuck latch on the Data Grapple Fixture at the front of Zarya. This would extend the operating envelope of Canadarm2 across to the Russian segment to support robotics work. A further material experiment was also deployed from a carrier located on the station’s truss. This was the eighth such experiment, with this one focused upon optical reflection materials. Originally attached during STS-134, it had not been deployed due to concerns from outgassing from the AMS unit. Finally, to close out the EVA, insulation was installed on the end of the Tranquility PM A in an area that was exposed to the effects of sunlight.

Throughout the mission, the Shuttle crew received a number of special wake-up calls in celebration of the end of the program. On July 11, much was made in reports of an “all American meal” which featured grilled chicken, corn, baked beans, cheese, and the traditional apple pie. This was also reported on the NASA website. The meal was originally planned for July 4, but the launch delays postponed it for a week.

On July 15, almost at the end of the 30 yr Shuttle program, U. S. President Barack Obama called Atlantis, wishing them well on their mission. The crew later solved a problem with the fourth general purpose computer on Atlantis, which required it to be rebooted to get it up and running again. Later, the EVA suits were reconfigured in order to leave them behind on the station. As the checklist of tasks remaining shortened, so the four Shuttle astronauts supported the station crew in relocating some of the cargo they had delivered to ease the post-docking workload for the resident crew as much as they could. The Shuttle crew also repaired a broken access door to the Shuttle air revitalization system, where the lithium hydroxide canisters that purified the air inside the orbiter were exchanged. On July 16, the 42nd anniversary of the launch of Apollo 11, Ferguson formally presented the station crew with the historic U. S. flag that had flown aboard Columbia on STS-1 30 years before. This flag will remain on board the space station until the next crew launched from the soil of the United States arrives at the orbiting facility to return it to Earth once again.

Hatches between the two spacecraft were closed for the final time on July 18 after 7 days 21 hours and 41 minutes. The next day, after a few hours’ sleep on board Atlantis, the crew undocked from the station after 8 days 15 hours and 21 minutes of being attached to the orbital facility, ending a period of Space Shuttle station dockings that had begun 16 years before, with the flight of STS-71 to Mir in 1995. Safely undocked, the crew backed the orbiter away for the formal fly-around maneuver to photo-document the exterior of the station. The station was yawed 90 degrees for an optimum view during the 27 min photo opportunity, which captured never-before-seen views of the longitudinal axis of the station from the Shuttle. With this completed, it was time to fire the separation engines and depart from the vicinity of the station to begin final preparations for the flight home.

On the day before landing (July 20), the crew performed the traditional pre-landing checks of the Thermal Protection System, Flight Control Systems, and RCS engines for the final time on a Shuttle mission. The last science objectives of the program were completed with the deployment of the PicoSat technology demonstration satellite from a small canister in the payload bay and an onboard experiment on osmosis was also conducted by the crew. On July 21, to the wake – up call of God Bless America by Kate Smith, there was a tribute to all those who had been involved in the program since its inception over 40 years ago. Even the weather was cooperating, helping to celebrate the end of an era of American manned space flight in fine style as Atlantis swooped to a perfect pre-dawn landing at the Cape.

By the end of its last mission, Atlantis had traveled 125,935,769 million miles (20,263,063 km) over 33 missions, logging over 307 days in space, and completing 4,848 orbits of Earth. When the crew disembarked, there remained only the period of decommissioning after the mission and then a program of preparations for shipping the Atlantis to its new museum home. But before the vehicle had cooled down from its fiery reentry, the celebrations and emotional recollections had begun. For commander Ferguson, the realization that the Shuttle program was over came when the wheels stopped on the runway and the vehicle was powered down. In the pre-dawn darkness the displays went blank and the vehicle fell silent, creating a “rush of emotion” for the commander.

The Shuttle program had created many milestones and memories over 30 years, but never again would an orbiter of that design venture into space. Its work was done and it was time to move aside for new generations of human spacecraft to write the next pages in space history. The Shuttle era was finally over.

Milestones

284th world manned space flight 165th U. S. manned space flight 37th and final Shuttle ISS mission 135th Shuttle flight 33rd and final Atlantis flight 12th Atlantis ISS flight Final Shuttle flight of program

First four-person Shuttle crew since STS-6 in April 1983