. SOYUZ TMA-21

Flight crew

SAMOKUTYAEV, Alexander Mikhailovich 41, Russian Federation Air Force,

RSA Soyuz TMA commander/ISS-27/28 flight engineer

BORISENKO, Andrei Ivanovich, 46, civilian, RSA Soyuz TMA flight

engineer/ISS-27 flight engineer/ISS-28 commander

GARAN Jr., Ronald John, 49, USAF (Retd.), NASA Soyuz TMA and

ISS-27/28 flight engineer, second mission

Previous mission: STS-124 (2008)

Flight log

It was poignant that the next manned launch was Russian, as it occurred just eight days before the 50th anniversary of the world’s first manned space flight, by Yuri Gagarin in Vostok on April 12, 1961. The radio call sign for Soyuz TMA-21 became “Gagarin” in celebration of that historic event. It was also fitting that the crew emblem of this Russian/American crew featured the name of (Alan) Shepard, the first American in space (suborbital), just three weeks after Gagarin’s flight. It was an excellent way of linking the early pioneers to the modern day space explorers. The contrast between these two eras is readily apparent in the flight durations. The combined flights of Gagarin and Shepard logged just over 123 minutes in flight, whereas the TMA-21 crew were embarking on a 165-day mission, joining the crew that was already on the station when the “Gagarin” Soyuz left the pad.

The TMA-21 mission continued the uninterrupted science work on board the station, and would also be noted for receiving the final Shuttle missions on the manifest. In the Russian segment, the ISS-27/28 increment was planned to

|

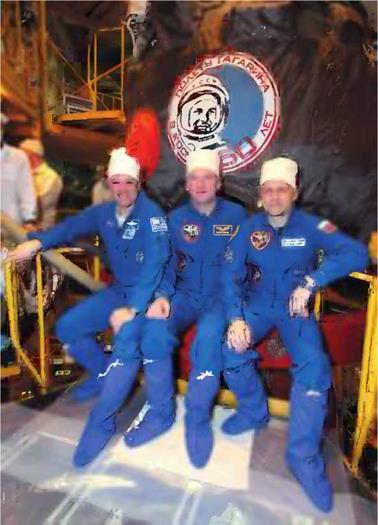

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of Gagarin’s historic journey. Garan, Samokutyaev, and Borisenko pose outside their Soyuz TMA-21 spacecraft, which bears the likeness of the first cosmonaut, and was given the call sign Gagarin in honor of the celebration. Photo credit: NASA/Victor Zelentsov. |

conduct a program of 725 sessions covering 50 experiments, of which only three were new. To accomplish this, the Russian crew members were assigned 174 hours 25 minutes of experiment time during the ISS-27 phase and 359 hours 20 minutes under the ISS-28 program. Across in the American segment, there were a further 111 experiments, supported by a network of over 200 researchers around the world. NASA was sponsoring 73 of these experiments, with 22 under the auspices of the U. S. National Laboratory program and another 38 experiments sponsored by other partner agencies. These would take up over 540 hours of crew time.

This increment continued the rotational 3/6/3/6 crewing sequence of earlier expeditions. A three-person crew operated ISS-27 from March 16 to April 6, with the crew of six operating between May 7 and 24. The ISS-28 crew continued as a three-person occupation from May 24 to June 9, returning to a six-person crew between June 10 and September 16. This was of course very positive for the operational side of the ISS program and the overall long-term expansion of human space exploration at large. However, for those who record the assignments and activities for each space explorer or expedition, it was becoming more difficult to keep track of individual records as one expedition blended into the next.

The April 7 docking with Poisk was followed three hours later by crew transfer into the main station compartments. The combined crew completed the usual welcome and safety briefings procedures, highlighted by speaking to their families at Mission Control in Korolev (Moscow). One amusing incident occurred when Garan’s wife reminded him that she was safely holding his credit card while he was “out of town”. The Soyuz was mothballed on April 7 and the crews got down to their well-orchestrated blend of science, maintenance, housekeeping, safety, and some time out for sleep and personal hygiene.

The first scheduled visitors, on STS-134, were delayed by technical problems preventing the launch, so the resident crew continued with their own program, demonstrating the flexibility of the timeline of long space flights. The Shuttle mission finally arrived on May 18 and this was followed by the departure of the TMA-20 crew, signaling the end of the ISS-27 expedition with their undocking on May 23. Handover of command between Kondratyev and Borisenko had taken place the day before.

The crew continued as a three-person residency until the arrival of the Soyuz TMA-02M on June 9. During the residency, the complex was reboosted several times using the engines on the ATV-2, to maintain its operational altitude while the science program continued on board the station. In July, the final Shuttle mission (STS-135) visited the station, marking the end of Shuttle operations. From this point, the Soyuz and Progress vehicles of Russia, Europe’s ATV, and Japan’s HTY would be the only operational resupply systems for the station. There were plans under way to launch new commercial vehicles to the complex, in order to test the feasibility of such systems for future use. It also emerged that detailed studies were under way to evaluate the use of the station up to 2028, if the partners could verify that the various components could work effectively and safely for that long.

On August 1, Samokutyaev and Volkov completed a 6h 23min EVA, deploying scientific experiments and an experimental high-speed laser communication system outside the Russian segment. The two cosmonauts also removed a rendezvous antenna which was no longer needed and deployed by hand a small, 571b (25.85 kg) ham radio satellite, as part of the 50th anniversary celebrations of Gagarin’s flight in Vostok. A planned relocation of the Strela-1 (“Arrow-1”) crane was postponed until 2012. The final task was to have photographs taken, with the two men holding pictures of Gagarin, spacecraft designer Sergei Korolev, and space theorist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and using the Earth as a backdrop. The three images had been displayed inside Zvezda for years and were returned there after their trip into open space.

Later that month, on August 24, station operations were dealt a blow with the loss of Progress M-12M some 5 minutes 25 seconds into the launch phase. The Soyuz-U (R-7) launch vehicle’s third stage ignited for 25 seconds but, following a loss of pressure, promptly shut down resulting in a loss of velocity and subsequent crash. This was the first ever loss of a Progress craft during launch since the series began back in 1978. On board the resupply craft was 5,8631b (2,659 kg) of supplies, propellant, and oxygen. Repercussions from this loss included delaying the landing of the TMA-21 crew by a week, but the TMA-02M crew would return as planned in mid-November. The next manned flight would have to be delayed from September 22 to late October or early November.

The Soyuz TMA had an on-orbit operational life (mothballed and docked with the ISS) of 210 days and there were more than enough supplies on board the station (thanks to the final Shuttle flights) to keep a crew sustained for over a year, so there was no immediate risk to the crew on board. Nevertheless, it was still a difficult time for the Russians, with talk of lack of confidence in their space hardware and manufacturing/processing systems and the potential prospect of abandoning the station by all crew members if the R-7 could not be recertified for operations. After the next two unmanned launches, one commercial and another Progress, this requalification would come during the ISS-29 crew duty shift; the ISS-28 crew was due to come home.

After the delay due to the loss of the Progress resupply craft, the handover of station command from Borisenko to Fossum took place on September 14. The TMA-21 crew returned to their Soyuz craft and closed the hatches late on the following day, with undocking occurring in the early hours of September 16. There was some anxiety in Russian Mission Control after the planned 3 min blackout period, when communications with the cosmonauts in the Descent Module could not be established. Fortunately, contact was soon restored and the trio landed safely, apparently unaware of any communication problems.

During the 165-day flight, the crew logged approximately 162 days on board the station, with 160 days as part of expeditions. This included 45 days as members of the ISS-27 phase and 115 days as the prime ISS-28 crew.

Milestones

281st manned space flight 115th Russian manned space flight 108th manned Soyuz 21st manned Soyuz TMA 26th ISS Soyuz mission (26S)

27/28th ISS resident crew

Became the last crew to host a visiting Shuttle mission (STS-135)

Borisenko is accredited with being the 200th person to enter the ISS facility

|

Flight crew

KELLY, Mark Ehward, USN, NASA commander, fourth mission Previous missions: STS-108 (2001), STS-121 (2006), STS-124 (2008) JOHNSON, Gregory Harold, USAF (Retd.), NASA pilot, second mission Previous mission: STS-123 (2008)

FINCKE, Edward Michael, USAF, NASA mission specialist 1, third mission Previous missions: Soyuz TMA-4/ISS-9 (2004), Soyuz TMA-14/ISS-18 (2008) VITTORI, Roberto, Italian Air Force, ESA mission specialist 2, third mission Previous missions: Soyuz TM-34 (2002), Soyuz TMA-6 (2005)

FEUSTEL, Andrew Jay, civilian, NASA mission specialist 3, second mission Previous mission: STS-125 (2009)

CHAMITOFF, Gregory Errol, civilian, NASA mission specialist 4, second mission

Previous mission: STS-124/126/ISS-17/18 (2008)

Flight log

The 25th mission of Endeavour, the last vehicle to join the fleet in 1992, was also to be its final space flight. Designated STS-134, this was a utilization and logistics mission that had originally been manifested as the final flight in the Shuttle program, until STS-135 was added. Endeavour’s swansong delivered the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer-2 (AMS-02) experiment to the space station. This is a particle physics detector designed to search for a range of unusual matter by measuring cosmic rays. It was planned that the gathered data would be used in research into the study of the formation of the universe, in the search for evidence of dark matter, strange matter, and antimatter. In addition to the AMS, Endeavour carried the ExPRESS Logistics Carrier-3 (ELC-3), a platform full of spares. The mission would also see the final scheduled EVAs by Shuttle crew members, ending an impressive 28 yr series of space walks by orbiter crews.

|

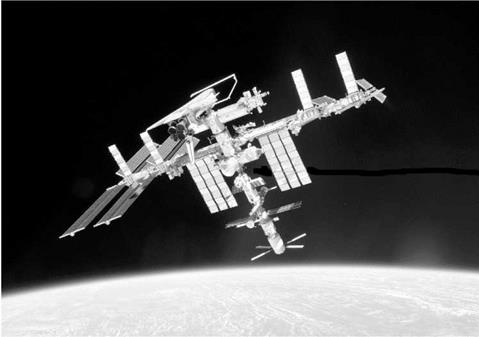

One of the first pictures of a Shuttle docked with the ISS from the perspective of a Soyuz spacecraft (TMA-20). |

The original launch date in March was delayed due to technical issues. This was also compounded by the tragic shooting in Arizona of Congresswoman Gabrielle Gifford, the wife of mission commander Mark Kelly. The event also placed NASA in a difficult situation, if Kelly required more time with his wife as she recovered. Replacing a commander of a mission so close to launch had never occurred in previous missions, so veteran Shuttle commander Richard Sturckow was assigned as backup commander as a precaution. Gabrielle Gifford’s recovery was remarkable, to the point that she was able to attend the planned April 29 launch attempt. However, as a result of technical problems with an Auxiliary Power Unit on the Shuttle, the launch was canceled four hours prior to liftoff and postponed until May. Fortunately, Gifford was also able to make it to the Cape to witness the May 16 launch, unlike U. S. President Barrack Obama and his family, who had witnessed the April 29 abort, toured the center, and met with the Gifford’s but were unable to reschedule a visit for the May launch. The series of delays also meant that Mark Kelly would not join his twin brother Scott in orbit. Scott had been on the space station since the previous October and was the serving space station commander, but returned home before STS-134 launched.

Endeavour and its experienced crew of six left the pad at KSC for the final time on May 16, 2011, just over 50 years after Alan Shepard became the first

American in space on May 5, 1961, and nine days prior to the 50th anniversary of President John F. Kennedy’s commitment to place Americans on the Moon by the end of 1969. Though the entire Endeavour crew consisted of space flight veterans, Fincke and Vittori were making their first flights on the Shuttle, having previously flown to the ISS atop Russian rockets aboard Soyuz spacecraft. Vittori became the final non-NASA astronaut to fly a Shuttle mission.

During the standard 2-day flight to the ISS, the Shuttle crew checked out the RMS and used it to examine the Thermal Protection System. Meanwhile, the EVA crew prepared the EVA suits and equipment. The crew was also scheduled to evaluate the Sensor Test of Orion Relative Navigation Risk Mitigation (STORRM) during their mission. This equipment evaluated sensor techniques for routine spacecraft docking with the ISS. Evaluations would be taken during rendezvous and docking and a later re-rendezvous with the station following the undocking towards the end of the mission.

Endeavour completed its 12th and final docking with the ISS on May 18 at PMA-2, with internal hatches opened just a few hours later. Following the usual welcoming ceremony and safety briefings by the resident station crew, the joint program of activities began. The ELC-3 pallet was transferred from the RMS to Canadarm2 some 5 hours after docking and was then installed on the P3 truss. Loaded on the pallet were two communication antennas, a high-pressure gas tank, and spare parts for the Dextre robotic device. The next day, the AMS-02 unit was transferred to the top of the S3 truss, where it is scheduled to remain to at least 2020. To avoid interference with other systems and storage platforms, the unit was installed at a 12° angle. The AMS science program is a global program involving 600 scientists and technicians from 56 institutions across 16 nations. The simpler AMS-01 flew on the Shuttle in June 1998, as part of the STS-91 payload.

During the mission, Italian astronaut Roberto Vittori carried out a program of six ASI-sponsored experiments under the DAMA Mission (named for the AMS search for dark matter). Vittori served as a test subject of two ESA experiments which studied possible changes to his body after the flight. This was part of a program of investigations in the fields of technology, nuclear power, biology, and materials. The Italian astronaut also assisted in the transfer of cargo into the station and unwanted material back into the orbiter.

The mission included four EVAs, totaling 28 h 33 min, shared between Feustel, Chamitoff, and Fincke. The first EVA (May 20, 6h 19 min) was conducted by Feustel and Chamitoff. They installed an ammonia jump cable that would connect the coolant loops of the station’s P3 and P4 segments, installed a cover on an SARJ and removed the MISSE 7A and 7B experiment packages from the Express Logistics Carrier-2, replacing them with the MISSE-8 experimental package. An external communication antenna was also installed on the Destiny Laboratory, to provide a link between the various ExPRESS Logistics Carriers mounted on the outside of the station. An issue with a carbon dioxide level sensor on Chamitoff’s suit caused concern in the latter stages of the EVA, with some tasks delayed to a subsequent space walk to maintain safety. Prior to this there had been no indication of a C02 problem, but the EVA ended a little earlier than planned and the issue did not reoccur.

The second EVA (May 22, 8h 7 min) by Feustel and Fincke featured a program of maintenance work. They refueled one of the station’s port side cooling loops with 51b (1.26 kg) of ammonia and also lubricated the port side SARJ and one of the “hands” on Dextre. Storage beams were fixed on the SI truss segment and a camera cover was installed on Dextre to end the space walk.

Between the second and third EVAs, the resident station crew was reduced from six to three with the departure of the ISS-27 crew in Soyuz TMA-20 on May 23. The delay in launching Endeavour, coupled with a delay in undocking the Soyuz, had created the unique situation of a Shuttle being docked with the station during the departure of a Soyuz crew. The remaining three TMA-21 crew members on the station now became the ISS-28 resident crew. As the TMA-20 retreated to about 600 ft (182.88 m) away from the Rassvet Module, Nespoli took a series of stunning digital images and video of Endeavour docked with the station from the viewing port in the Soyuz Orbital Module. At the same time, the whole station was rotated about 130°, which was a rare maneuver in itself, allowing the Italian astronaut some of the best views possible during a 30 min period.

Looking towards the future, the third EVA made use of a new EVA prebreathe protocol, known as the In-Suit Light Exercise (ISLE). Instead of the normal Campout Pre-breathe Protocol System, where the astronauts breathe pure oxygen for 60 minutes in the airlock, this new technique saw the air pressure of the airlock lowered to 10.2 psi (703 hPa). The astronauts then put on their space suits and performed light exercise, before resting for an additional 50 minutes, breathing pure oxygen all the while prior to exiting the airlock to conduct the EVA.

Activities during EVA 3 (May 25, 6h 54 min) completed by Feustel and Fincke included an upgrade to Canadarm2, installing a power and data grapple feature on the Russian Zarya module that would enable the station arm to “walk” across to the Russian segment and conduct robotic operations there. This had not been possible before and would now extend the range of the station’s robotic arm system. The astronauts also installed additional cables between the American Unity module and the Russian Zarya module, which would provide backup power to the Russian segment. A series of photos were taken of the effects of the Zarya thrusters on the skin of the module, along with verbal information on the condition at various work sites which was relayed to the ground. The astronauts also completed the work postponed from the first EVA due to the suit malfunction.

The fourth and final EVA (May 27, 7h 24 min) by Fincke and Chamitoff was the last scheduled EVA by a Shuttle crew, ending a program which had started back in 1983 during STS-6. It had included 162 excursions, many of these essential for station assembly since 1998. Ironically, the final “Shuttle” EVA was not actually from a Shuttle Orbiter, but from the Quest airlock on ISS. The last EVAs directly from a Shuttle Orbiter had occurred in 2009 during the STS-125 Hubble Servicing Mission. Since 2001, most Shuttle crew EVAs had actually been from the Quest airlock on the station rather than through the middeck airlock/hatch system on the orbiter. For this final EVA, the astronauts assisted with the transfer of the 50 ft (15.24m) Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS) from the orbiter across to the starboard truss and installed a new grappling system, extending the reach of the station’s robotic arm even farther. This EVA also saw station EVA operations pass the 1,000 h mark since assembly began in December 1998.

In three space walks, Fincke logged 22 hours 25 minutes, while Feustel accumulated 21 hours 10 minutes. Chamitoff recorded 13 hours 43 minutes in his two trips outside. The EVAs were followed by the completion of cargo transfers and logistics to and from the ISS.

The astronauts conducted a number of media and public outreach activities before undocking from the station on May 29, after 11 days 17 hours and 41 minutes attached to the complex. A fly-around and photo-documentation of the station’s exterior was followed by a final test of the STORRM rendezvous system from 1,044ft (318.21m) below and 300ft (91.44m) behind the station. When Endeavour landed at KSC, the youngest orbiter had completed the 25th mission of its career, having traveled 122,883,151 miles (19,771,898 km) in 4,677 orbits of Earth and 299 days in space. Endeavour would remain at the Cape for decommissioning before being dispatched to its new museum home.

With the installation of the AMS-2 payload, the official assembly complete point of the U. S. segment was met. In fact, most of the station was now complete, with only a couple of Russian modules and some desired large experiments to be launched. The station was no longer a construction site but a research facility. This was made possible by the series of Shuttle assembly missions since 1998 … and now there was only one left on the manifest.

Milestones

282nd world manned space flight 164th U. S. manned space flight 36th Shuttle ISS mission 134 th Shuttle flight 25th and final flight of Endeavour 12th Endeavour ISS flight

Vittori first Italian ESA astronaut to fly on both Soyuz and Shuttle missions Last non-NASA astronaut to fly on a Shuttle mission (Vittori)