SOYUZ TMA-14

2009-015A March 26, 2009

2009-015A March 26, 2009

Pad 1, Site 5, Baikonur Cosmodrome, Republic of

Kazakhstan

October 11, 2009

Near the town of Arkalyk, Republic of Kazakhstan Soyuz-FG (serial number Ю15000-027),

Soyuz TMA (serial number 224)

198 da 16 h 42 min 22 s (ISS-19/20)

12 da 19 h 25 min 52 s (Simonyi)

Altair

ISS resident crew transport (18S), ISS-19/20 research program, visiting crew 16 program

Flight Crew

PADALKA, Gennady Ivanovich, 50, Russian Federation Air Force, RSA Soyuz TMA and ISS commander, third mission

Previous missions: Soyuz TM-28/Mir 26 (1998/1999), TMA-4/ISS-9 (2004) BARRATT, Michael Reed, 49, Civilian, NASA Soyuz TMA and ISS flight engineer 1

SIMONYI, Charles, 60, civilian, U. S.A., space flight participant, second mission Previous mission: TMA10/TMA9 (2007)

ISS resident crew (Shuttle) exchanges

WAKATA, Koichi, 45, civilian (Japanese), JAXA ISS flight engineer KOPRA, Timothy Lennart, 46, U. S. Army, NASA ISS flight engineer (up STS-127, down STS-128)

STOTT, Nicole Maria Passano, 46, civilian, NASA ISS flight engineer (up STS-128, down STS-129)

Flight log

By the spring of 2009, the station was ready for an increase in the permanent crewing from three to six. It had been decided to overlap main crews between expeditions, to help ease the strain on the station’s limited resources while the final Shuttle assembly missions were flown. The plan was to launch a main crew to the station aboard Soyuz ferry craft in two teams of three. One knock-on effect of this would be the serious restriction of the availability of spare Soyuz seats for fare-paying individuals (the space flight participants) for some time. Any available

|

The first two-flight space flight participant Charles Simonyi floats in the Harmony Node. |

seats would now be filled by representatives of the ISS partners (NASA, RSA, CSA, ESA, and JAXA).

Overlapping these crews meant that when the first crew of three returned, there would be a period when only a three-person (skeleton) crew would be in residency on the station until the next trio arrived to restore the crew to six. For brief periods, the ISS could support three Soyuz craft with nine crew members, but not for prolonged periods. In practice, Crew “A” would be joined by Crew “B” to create Residency “X”. Once Crew “A” departed, crew “B” would continue alone as Residency “Y” until they were joined by Crew “C”. When Crew “B” returned, crew “C” would assume the role of Residency “Z”, and so on. The crew of TMA-14 would complete the first move in this new system, along with the next crew on TMA-15, creating the residencies ISS-19 and ISS-20 (or ISS-19/20). The lead crew on any station expedition would be known as ISS “X” Prime.

Pioneering this change and in command of the TMA-14, as well as ISS-19/20, was veteran Mir and ISS cosmonaut Gennady Padalka. Accompanying him was NASA rookie flight engineer Michael Barratt and space flight participant Charles Simonyi on his second visit to the ISS. This was a first for a space flight participant. Simonyi had previously visited the station two years before and this time would complete a 13-day flight (at a reportedly higher price than his first visit) before returning with the ISS-18 cosmonauts in TMA-13. During his second residency, Simonyi conducted a small program of experiments which included photography, a radiation safety experiment, ham radio, and various symbolic activities. Some of these activities were in connection with ESA, the Hungarian Space Office (Simonyi being a Hungarian-born, naturalized U. S. citizen), and the Russian Space Agency. On April 8, 2009 Simonyi and the outgoing ISS-18 crew undocked from ISS and landed safely.

Padalka and Barratt officially joined Japanese astronaut Wakata (already on board the station) as resident crew members on April 2. This trio became ISS-19 and would also assume the lead role for ISS-20 from May until their departure in October. There were still two further Shuttle partial crew exchanges to come after Wakata (who would be followed by Timothy Kopra and then Nicole Stott), so three-person Soyuz crewing would not actually begin until the end of 2009. ISS-19 was an expedition in a period of transition at the station after a decade of assembly. It was also a clear demonstration of the program’s increased capabilities in manpower research and the often overlooked level of ground support across the globe.

With all the main laboratory facihties up and running, the research programs could also now step up. The Russian program for ISS-19/20 would see 330 sessions for 42 experiments, including four new research studies. The program encompassed life sciences, geographical research, Earth resources, biotechnology, technical research, cosmic ray research, education and space technology studies, and contract activities. Most of this research would be conducted by Padalka (in preffight planning this amounted to 164 hours), while Barratt focused on U. S. segment experiments. During the ISS-20 phase of his mission, ISS-20/21 flight engineer Romanenko would complete a further planned 160 hours of Russian segment science. In addition, NASA reported 98 experiments in human research, technology development, observations of the Earth, educational activities, and biological and physical sciences. Of these, 39 were new investigations, with 28 others originating from Europe, 16 from Japan, and 5 from Canada. There were 10 ongoing investigations from earlier expeditions.

One of the investigations highlighted by the world’s media were the studies in recycling urine into drinking water, clearly not one of the more glamorous aspects of a space explorer’s role. After receiving the all clear from ground tests on reclaimed water samples on May 20, a milestone was reached on board the station when ISS-19 crew members drank reclaimed and purified water from the Water Recovery System.

On May 29, 2009, the much anticipated transition from a three to a six-person crew was finally realized with the docking of TMA-15. On board were Belgian Frank De Winne (ESA), Russian Roman Romanenko (son of Salyut 6/Mir cosmonaut Yuri Romanenko), and Canadian Robert Thirsk. For the first time, each of the primary participants (Russia, U. S.A., Europe, Canada, and Japan) were represented in the resident crewing. Long in planning, the symbolic nature of the first six-person crew being comprised of crew members from the major ISS partners was not lost on the international agencies or world’s media.

The docking and transfer into the ISS of the new crew of TMA-15 signaled the official end of the ISS-19 residency. The three ISS-19 crew members remained on board, but now ISS-19 officially became ISS-20. It would remain so until shortly before the return of Padalka and Barrett in October, together with the final space flight participant who was scheduled to arrive on Soyuz TMA-16 with the ISS-20/21 crew.

The makeup of the expanded international resident team on station soon changed, however, with the exchange of crew members on Shuttle. In July, Wakata was replaced by Kopra during STS-127, which also delivered the next element of the Kibo laboratory. Kopra remained on station for just over a month until August, when STS-128 delivered his replacement, Nicole Stott. Stott in turn remained on board until November when she returned on STS-129. She was the final Shuttle-transported station resident crew member.

During the ISS-19 phase, no EYAs were accomplished by the resident crew. However, during ISS-20 Padalka and Barratt completed two short excursions totaling 5 hours 6 minutes wearing the new improved Orlan-MK suits. The first of these (June 5, 4h 54 min) featured additional preparations for the arrival at the Zvezda Service Module of the Mini Research Module-2. During the EVA, Wakata remained inside Zvezda, allowing access to TMA-14 which was docked with the module’s rear port. In the event of an emergency, the EVA crew could have proceeded to the Soyuz if they had been unable to reenter Pirs. Romanenko, De Winne, and Thirsk remained in the American segment close to TMA-15 on Zarya. Fortunately, all went well and these well-planned and practiced contingency procedures were not required.

The second activity, on June 10, was a 12 min intravehicular activity (IVA, crew activity while wearing a spacesuit inside an unpressurized spacecraft)—the first on station since 2001. During this IVA, Padalka and Barratt depressurized the Zvezda Node to relocate a conical docking cover over the zenith port so that the MRM-2 could dock there. Later, both Kopra and Stott would assist with Shuttle-based assembly EVAs from the Quest airlock during STS-127 and STS-128. These were not classed as part of the residency EVA program.

TMA-14 was moved on July 2 from the rear port of Zvezda to the recently vacated (by the departing Progress M-02M) port of Pirs. This freed up the Zvezda port for Progress M-67, which would be used to reboost the altitude of the complex. The other three crew members remained in the ISS during the Soyuz relocation operation, which took about 26 minutes, after which the Soyuz crew reentered the station. With half the crew remaining inside, partial shutdown of the station was no longer required, saving both crew time and valuable experiment operating time.

This operation was followed by the arrival of the STS-127 mission (July 1531) and later STS-128 (August 29-September 12). Another milestone was the arrival of the first Japanese HTV transfer vehicle on September 18, which was grappled by the station’s RMS. Its six tons of cargo would be transferred by means of the station’s robotic arms later.

In late September, the two ISS-20/21 crew members (Maxim Suraev and Jeff Williams) arrived with Canadian Space Tourist Guy Laliberte aboard Soyuz TMA 16. For a short time, the ISS included eight resident and one visiting crew member. On October 9, the formal change-of-command ceremony took place, with

Padalka handing over the reins to DeWinne. On October 11, Padalka, Barratt, and Laliberte transferred to TMA-14, undocked, and landed a few hours later. This expedition had seen a major milestone achieved in ISS operations and a highly successful period of activity, focused more on science than construction.

ISS-19/20 had logged almost 199 days in flight, of which 197 had been aboard the space station. The ISS-19 formal residency (April 2-May 29) lasted 57 days, while the ISS-20 residency (May 29-October 9) had logged 133 days, totaling 190 days of combined station command time for ISS-19/20.

Milestones

265th manned space flight 107th Russian manned space flight 100 th manned Soyuz flight 14th manned Soyuz TMA mission 18th ISS Soyuz mission (18S)

16th ISS Soyuz visiting mission 19/20th SS resident crew First ISS IVA in Zvezda node since 2001 First flight of Japanese HTV First ISS six-person residency (ISS-20)

Final planned three-person full resident crew (ISS-19)

First time representative from main ISS partners are represented on resident crew (NASA, RSA, ESA, CSA, JAXA)

Simonyi was the first space tourist to fly twice Final crew transfers via Shuttle (Wakata, Kopra, Stott)

Padalka celebrates his 51st birthday in space (June 21)

|

Flight crew

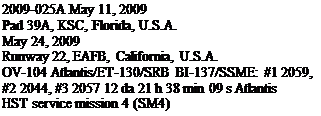

ALTMAN, Scott Douglas, 49, Captain USN (Retd.), NASA commander, fourth mission

Previous missions: STS-90 (1998), STS-106 (2000), STS-109 (2002) JOHNSON, Gregory Carl, 54, Captain USN (Retd.), NASA pilot GOOD, Michael Timothy, 45, Colonel USAF, NASA mission specialist 1 McARTHUR, Katherine Megan, 37, civilian, NASA mission specialist 2 GRUNSFELD, John Mace, 49, civilian, NASA mission specialist 3, fifth mission

Previous missions: STS-67 (1995), STS-81 (1997), STS-103 (1999), STS-109

(2002)

MASSIMINO, Michael James, 46, civilian, NASA mission specialist 4, second mission

Previous mission-. STS-109 (2002)

FEUSTEL, Andrew Jay, 43, civihan, NASA mission specialist 5

Flight log

STS-125 was the fifth and final servicing mission (SM) to the Hubble Space Telescope. It was also the sixth Shuttle mission devoted to the telescope’s orbital operations since 1990. The mission, as originally planned, was canceled in the wake of the 2003 Columbia tragedy, but was reinstated following a public and scientific lobby to fly one more Hubble-related mission. For space station Shuttle missions following the loss of Columbia, a rescue vehicle was prepared (normally as part of the next mission’s processing) and the station could be used as a safe haven until a rescue flight could be launched. As this was not a space station related mission and would be flying in a different orbit, the ISS was not an option. Instead, a second Shuttle was prepared on an adjoining pad as a potential rescue vehicle. When the Hubble flight was delayed and rescheduled, so too was

|

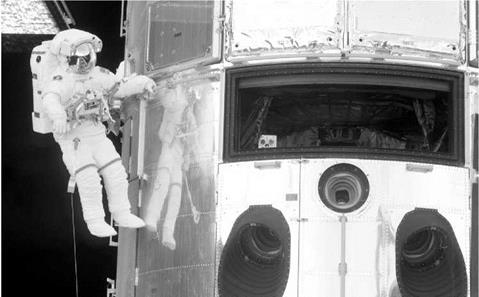

John Grunsfeld works on the Hubble Space Telescope on the first of five EVAs during the final servicing mission to the orbiting observatory. |

the rescue mission amended accordingly. The Shuttle Endeavour served as the backup rescue vehicle in a mission designated STS-400 (with a four-person crew). It remained on Pad 39B while STS-125 was in space, but once Atlantis was cleared for Earth return, Endeavour reverted to ISS mission preparations.

Atlantis preparations began in the OPF on February 20, 2008. The orbiter was subsequently moved across to the VAB on August 22 that year and the mated stack rolled out to Pad 39A on September 4, 2008. The mission was originally scheduled for October 2008, but was changed to February 2009 when the system that transfers science data from the orbital observatory to Earth malfunctioned. The mission was postponed again when delivery of a second data-handling unit to the Cape was delayed. This resulted in the rescheduled launch date of May 2009.

Prior to the rendezvous with Hubble, a thorough inspection of the Shuttle’s heat shield was performed using the RMS. The close-up imagery of the orbiter’s surfaces was relayed to MCC for analysis by specialist teams on the ground. During this analysis, the Mission Management Team (MMT) noted an area of damage on the forward part of Atlantis where the wing blends into the fuselage. This was apparently minor damage but additional expert analysis was still conducted to make sure. It was subsequently decided by the MMT that the thermal covering of Atlantis was indeed safe for reentry at the end of the mission.

Atlantis was guided by Altman, assisted by Good and the rest of the crew, to within 50 ft (15.2m) of Hubble on May 13. The telescope was grappled by the

RMS (controlled by McArthur) without incident and then maneuvered into a Flight Support System (FSS) maintenance platform in the orbiter payload bay. In addition to supporting Hubble, this platform would provide power for thermal control during the service period while aboard the orbiter.

Five EVAs, totaling 36 hours 56 minutes, were conducted, achieving all of the mission’s objectives. Two of them went into the record books as the sixth and eighth longest EVAs in history. Two new instruments were installed on the telescope and a further two repaired, restoring them to operational life. The EVA crew also replaced gyroscopes and batteries as well as installing new thermal insulation panels for protection in orbit. Grunsfeld and Feustel logged three space walks each, totaling 20 hours 58 minutes, while Good and Massimino completed two EVAs each totaling 15 hours 58 minutes.

During the first EVA (May 14, 7h 20 min), Grunsfeld and Feustel replaced the Science Instrument Command and Data Handling Unit (SIC&DHU) and installed the Wide Field Camera 3. Grunsfeld installed the soft capture mechanism for future (though not yet planned) service missions, which would be post-Shuttle retirement. Meanwhile Feustel installed two latches over center kits in order to ease the opening and closing of the large access doors on the telescope. On the second EVA (May 15, 7h 56 min), Good and Massimino replaced three ratesensing units which contained two gyroscopes each. Unfortunately, one of the replacement units would not fit, so a spare was used instead. The two astronauts also replaced a battery module from Bay 2 on the telescope.

The Corrective Optical Space Telescope Axial Replacement (COSTAR) was removed by Grunsfeld and Feustel on EVA 3 (May 16, 6 h 36 min). This had been installed during the first Hubble Service Mission in December 1993 to correct and refine the image generated from the telescope’s faulty main mirror. As it was no longer required, it was replaced with the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph. This new device would allow Hubble to peer farther into the depths of the universe than ever before, both in the near and far-ultraviolet ranges. Their next task was to repair the advanced camera for surveys, which involved the removal of 32 screws from an access panel, replacing the camera’s four circuit boards and installing a new power supply.

EVA-4 by Massimino and Good (May 17, 8h 20 min) included repairs to the telescope’s imaging spectrograph by replacing a power supply board. The astronauts experienced some difficulty with a handrail. This had to be removed before they could fit a fastener capture plate that was designed to retain over 100 screws during the removal of a cover plate. The astronauts found that a stripped bolt was preventing the handrail from coming free. They would receive guidance on how to overcome this problem from engineers at the Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC). Massimino eventually carefully bent and broke the handrail free to allow installation of the capture plate. This episode raised some concerns in Mission Control over the possibility of the effort involved causing damage to the astronaut’s pressure suit. All went well, though, and in fact was much easier than at first thought. However, the astronauts were unable to install a new outer blanket layer on the outside of Hubble Bay 8, so this task was delayed to the fifth and final EVA of the mission. This final EVA (May 18, 7 h 2min) saw Feustel and Grunsfeld exchange a battery module from Bay 3 for a fresh one, as well as removing and replacing the H2 fine guidance sensor. They were then able to install the new outer blanket layer on three bays outside the telescope.

The result of all this activity was a telescope with six working complementary science instruments. This gave Hubble a capability far beyond what was envisioned when the facility was launched in 1990 and an extended operational life to at least 2014. After Hubble was released on May 19, again using the RMS, a final separation maneuver was made and the berthing mechanism which had held Hubble in the payload bay during the mission was stowed for landing. The crew completed a further RMS-aided examination of the orbiter heat shield to search for any new damage from orbital debris but fortunately no significant damage was discovered.

The following day (May 20), the crew stowed gear and checked the RCS and flight control surfaces for entry and landing. The crew became the first to testify live from space on May 21, during a U. S. Senate Hearing in which they addressed the Senate Operations Committee, Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies, chaired by Senator Barbara Mikulski (Democrat) of Maryland. She was the political driving force behind getting the STS-125 mission authorized. She and former U. S. Payload Specialist Senator Bill Nelson of Florida also talked to the crew.

Weather concerns and conditions at the Cape during May 22, 23, and 24 forced three consecutive landing waive-offs, requiring Atlantis to land at Edwards AFB, California on May 24, 2009. Just over a week later, the orbiter was ferried back to KSC on the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, arriving back in Florida on June 2 after a two-day ferry flight. STS-125 had been a highly successful mission. Despite the apprehensions over flying an independent mission which could not visit the space station, the flight passed without major incident, ending a highly successful series of Hubble-related missions.

Milestones

266th manned space flight 156th U. S. manned space flight 126th Shuttle mission 30th flight of Atlantis 6th dedicated Shuttle HST mission 5th HST servicing mission Heaviest payload carried to Hubble on the Shuttle Final “solo” Shuttle mission of program Only post-Columbia-loss non-ISS Shuttle mission