A fourth decade of experience

There were three streams to manned space flight operations during the 1990s. First, the main Shuttle program completed a range of independent engineering, science, deployment, and servicing missions. The Russian national Mir program flew a series of long-duration expeditions and a number of shorter visiting missions, some of which were international cooperative ventures. The third element was the Shuttle missions associated with the ISS program, including the series of rendezvous and docking missions with the Mir station and the start of ISS assembly operations.

For the Shuttle program, an important learning curve was climbed by sending orbiters to the Russian Mir station. When Space Shuttle was originally proposed, one of its major objectives was to create and support space station operations. This objective was lost in the early years of Shuttle operations and almost forgotten well into the 1980s, but by the 1990s the Shuttle finally had an objective and the target it was designed for. As plans to send the Shuttle to a space station were finalized, the 1990s also saw a range of missions flown by the Shuttle which at times seemed very much like cleaning a house: flying long-delayed missions, adapting others to support the new Mission to Planet Earth program; expanding the scope of the Hubble Space Telescope and deploying other great observatories and research satellites; and preparing for the start of ISS construction.

It is amazing now to look back at this period. It was a time of great change in the Soviet Union and a struggle for funding for the new Russian space program. Across the Atlantic, there were similar difficulties in securing a future for the U. S. Freedom station and continuing with Shuttle operations. The unique circumstances of these events allowed both nations to come together and, with some effort, overcome their differences to launch a true partnership that was extended to include 16 nations, creating what we now know as the International Space Station. The program of cooperation has, in hindsight, allowed the creation of the ISS to run relatively smoothly during the last decade or so, even with further tragic setbacks and operational hurdles to overcome.

The Mir program was the cornerstone for both the Russians and, to an extent, the Americans to progress on to the ISS. One of the most important lessons learned from Mir was adaptability. Being able to adapt flight plans, overcome difficulties, and have the skills, alternative systems, and procedures to keep flying was a testament to the robust nature of the Soviet/Russian hardware, if not its refined technology. Being prepared for the unexpected was a lesson well learned by the Americans during the seven residencies on the station.

During Mir, something new was learned on every expedition; there were often unexpected lessons. It was surprising to some how long the program continued to be operational. Mir, as a space complex, had been continuously manned between September 7, 1989 and August 27, 1999 by a succession of crews for 3,640 days, 22 hours, and 52 minutes. That record has now been surpassed by the ISS, but at the time this was a huge achievement, especially with the difficulties in keeping the station flying at all in its latter years. Often overlooked was the significant amount of science research conducted on the station over a period of 14 years. By 2000, the station had over 240 scientific devices on board with an accumulated mass of over 14 tons. Over 20,000 experiments had been conducted (see Andrew Salmon’s “Firefly” in Mir: The Final Year, edited by Rex Hall, p. 8, British Interplanetary Society, 2001).

It was not smooth sailing by any means. Simply maintaining Mir systems began to consume most of the main crews’ time on board, as did trying to find places to store unwanted equipment. Once cosmonauts began to make return visits to the station, sometimes years apart, they reported that the time spent on repairs had increased significantly over their earlier tour. They found equipment already stored in locations meant for experiments to be set up, which caused valuable experiment time to be lost because of relocating the logistics. International crew members described finding equipment on board the station a nightmare, with conditions on the station reported as detrimental to an efficient working environment. But much of this would prove valuable for the new ISS program. In quantifying the value of their series of missions to Mir and supporting the seven NASA residencies, John Uri, the NASA mission scientist for Shuttle-Міг, commented in the fall of 1998 that NASA had developed a host of lessons learned from Phase 1 operations at Mir. Of these, he estimated that 80-90% would have useful and direct application for the planned science program on the ISS. The others were somewhat peculiar to performing science on Mir; yet there is always something to be gained. Clearly identifying what not to do can be an equally valuable lesson as learning how to approach and complete a task.

|

A view of the completed International Space Station from STS-135 in July 2011, the final Shuttle mission. |

2001-2010: THE EXPANSION YEARS

From the start of the new decade and the new millennium, the emphasis of human space flight focused around the creation and operation of the International Space Station. All but 3 of the 31 Shuttle missions flown in this decade were associated with the assembly and supply of the station. The first non-ISS mission was the fourth Hubble Servicing Mission, SM-3B (STS-109) in 2002. The second conducted ISS-related science, but flew independently of the station. This was the research flight STS-107, which ended tragically on February 1, 2003, with the high-altitude destruction of Columbia just 16 minutes from the planned landing. Following the loss of a second orbiter and crew in 17 years, the decision was made to retire the fleet. Originally, this was expected to be in 2010 but this was subsequently delayed until 2011, after 30 years of flight operations. As a result of the Columbia tragedy and inquiry, there was a review of the remaining payloads and hardware still to be launched to the station and a revised launch manifest was released for the remainder of the program, now with some of the planned elements deleted from the schedule. Once the Shuttle completed its return to flight qualification in 2006, there were no further serious delays in completing ISS assembly and finally retiring the Shuttle fleet.

In addition to the effort to complete the ISS, there was a move to fly one more service mission (SM-4) to Hubble. This had originally been canceled following the Columbia loss but was reauthorized after lobbying from the scientific community and the public. This third non-ISS mission of the decade was flown with great success, as STS-125 in 2009. The flight rounded out an impressive series of six missions specifically associated with the telescope but, sadly, the end-of – mission return to Earth on board a shuttle for the Hubble, which was on the manifest for about 2013 prior to the loss of Columbia, had to be abandoned. Had this been possible, a significant amount of information could have been gained from studying the telescope’s physical structure after over 20 years in orbit, prior to displaying the historic spacecraft in a museum for public viewing.

For the Russians during the first decade of the new millennium all effort was focused on supporting ISS operations, with the slow expansion of the Russian segment but regular resupply via Progress unmanned freighters. The venerable Soyuz was still in service at the end of the decade and in a new variant, the Soyuz TMA-M. This was the fifth major upgrade to warrant a separate designation. Though other vehicles have often been proposed by the Russians as Soyuz replacements, the almost 50-year-old design remains the primary crew ferry and rescue vehicle. In the period of 2003-2006, while the Shuttle was grounded or being requalified for operational flight, only the Soyuz was able to ferry crews to and from the station. It enabled the station to continue to be manned and operated, albeit with a reduced two-person caretaker crew. In hindsight the option taken in the early 1990s to include Soyuz in the program has been, with the grounding and eventual retirement of the Shuttle, a wise one and has saved the ISS program until something else replaces the Shuttle orbiter to take American astronauts into orbit.

|

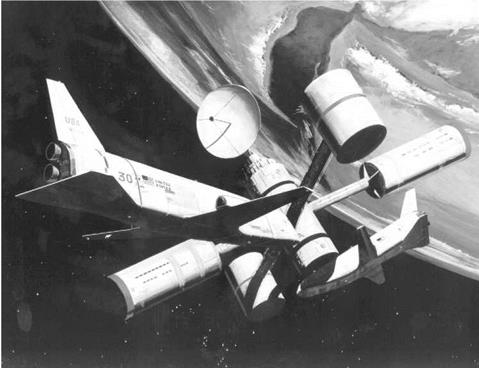

What could have been—a 1969 artist’s impression of NASA’s large space station with an early design of the Space Shuttle nearby. |