January 1986

To make the Shuttle more commercially viable, and to address the lack of room in the lower deck of the orbiter when not flying Spacelab, a commercial augmentation module called Spacehab had been designed. This would add over 50 new lockers to the capacity, partly in an attempt to promote the commercial potential for small experiments and payloads to the wider market. The reduced launch loads on the Shuttle (compared to the earlier ballistic capsule launches) allowed NASA to relax the selection criteria for passengers. Following politicians and a Saudi royal prince, a U. S. schoolteacher was to be launched on the 25th mission and a U. S. journalist was being selected to follow on a later mission. There were unofficial reports of potentially flying artists, singers, poets, and other celebrities; perhaps even actors to film scenes for a “space movie”. The Shuttle offered greater potential to fly in space than any other program before it, if it could be proved that it was a safe and reliable system for those who wanted to step aboard.

All these hopes for what Shuttle might have delivered tragically ended with the loss of Challenger and her crew of seven, including schoolteacher Christa McAuliffe, on January 28, 1986 (19 years and one day after the loss of the Apollo 1 crew). The tragedy occurred in full view of the TV cameras and disbelieving

|

Atlantis OV-104 performs a flight readiness firing (FRF) of its main engines prior to its first launch. |

onlookers at the Cape. It was one of those horrible moments in history that those who witnessed the events, or watched the news, would never forget. On that day, the hopes of the American space program fell from the sky along with the wreckage of Challenger. As President Reagan observed during the nation’s mourning, the brave crew of Challenger had “slipped the surly bonds of Earth and touched the face of God.” In the quest for space, the reality of the dangers that each crew face was clearly revealed in the tragic events on that cold day in January.

As part of the inquiry into the tragedy, the Shuttle fleet was immediately grounded and all mission training halted. For the next two and a half years, while the accident was investigated and recommendations instigated, payloads were canceled, delayed, or reassigned to expendable unmanned launch vehicles. NASA was closely scrutinized. The agency would never be the same again. Many employees had left after the end of the Apollo program, taking with them the skills and experience that took America to the Moon. Now, another serious blow to the program would lead to further changes to the agency, not only for the Shuttle program but for NASA itself. It was another dark time for American manned space flight.

|

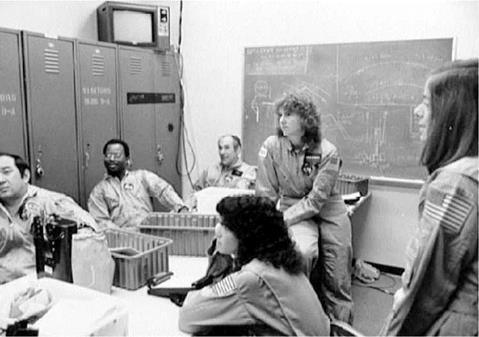

Crew of STS-51L Challenger during a mission briefing (left to right): Onizuka, McNair, Jarvis, Resnik, McAuliffe (teacher in space), and backup Barbara Morgan. |