The dawn of the Shuttle era

The Shuttle program had evolved over the previous two decades and had gone through a multitude of designs and formats before the final configuration was decided upon in the early 1970s. The winged spacecraft, with a huge cargo bay and two-deck crew module, would be launched like a rocket, powered by two solid rocket boosters and three liquid-fueled main engines. These would be fed with fuel from a giant external tank attached to the SRBs, under the belly of the

|

Testing Shuttle Enterprise from the back of a jumbo jet (1977). |

Shuttle orbiter. The spent boosters jettisoned after two minutes and completed a parachute landing before being retrieved from the Atlantic and towed back to the Cape for refurbishment and reuse. After fueling the main engines up to orbital velocity, the external tank separated after 8 minutes and burnt up in the atmosphere.

Once in space, the orbiter’s own maneuvering engines could place it into its required orbit. Now, the Shuttle would become a spacecraft, flying a range of missions of up to two weeks, but nominally between 7-10 days. These missions would feature a changing configuration of payloads, spacecraft, and hardware in the huge payload bay, demonstrating the flexibility and variety the Shuttle could offer to customers and investigators. The payloads would include commercial satellite deployments and retrievals, the development of on-orbit satellite servicing, and a range of science missions with a variety of payloads, carried in European – developed Spacelab pressurized laboratory modules or on unpressurized pallets. There were also planetary probes and large observatory deployments planned and

|

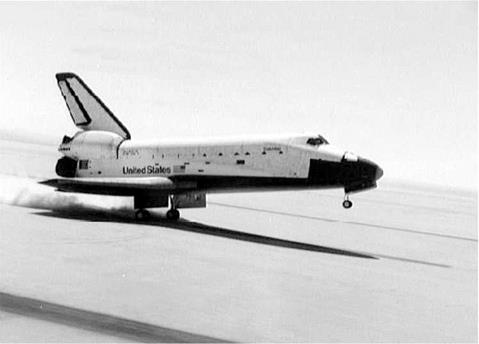

Columbia OV-102 lands at the end of the first Shuttle mission. |

a number of classified military missions manifested. At the end of the mission, the orbiter would reenter and complete an aerodynamic, unpowered, glider-style approach, landing on a runway near to its launch site to enable a quick turnaround for its next flight. That was the plan.

The composition of Shuttle crews would be a mix of pilots to fly and command the mission and mission specialists to handle payloads, the robotic arm, and space walks. There would also be occasional payload specialists, chosen for specific or one-off missions. The orbiter had the capability to support multiple space walks from an integral airlock using a wide range of support equipment, including (in the early years) a manned maneuvering unit for untethered operations close to the orbiter (for safety reasons). Another innovation was the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS), or robotic arm, which could lift large items out of and back into the payload bay, or support EVA astronauts in their spacewalking tasks.

The original plan was to fly one mission approximately every two weeks from converted Apollo launchpads in Florida and then introduce a series of high – inclination (polar) military launches from the USAF complex at Vandenberg AFB in California. To meet this expected demand, a fleet of orbiters would be required. In 1977, the orbiter Enterprise (OV-101) had been flown on the back of a converted Boeing 747 (which would also serve as a carrier aircraft for the orbiter

|

Challenger OV-099 launches on her maiden mission. |

when required) to evaluate the atmospheric qualities of the design on a series of approach and landing tests. These were supplemented by a series of ground tests and launchpad evaluations prior to the first manned launch. That historic launch occurred on April 12, 1981, the 20th anniversary of Gagarin’s flight. STS-1 was a stunning success and signaled the start of an impressive series of missions which would stretch across the next three decades. STS-1 was also the first U. S. manned space flight which had not been preceded by an unmanned space flight test prior to committing a crew to a new vehicle. This was a huge gamble, but it paid off.

Despite the success and proof of concept of the Space Transportation System over the next five years, the demand for commercial launches was not as great as expected and, consequently, the predicted reduction of launch and operating costs did not materialize. It was not all down to marketing the Shuttle as an all – encompassing national launch system. There were ongoing difficulties in preparing the vehicle for launch because the process was complex and not as routine as expected. This affected launch manifests and thus “selling” the Shuttle to farepaying customers, who were looking for an affordable, dependable, and reliable system free from delays and mishaps. On top of this, the military never fully adopted the system for its own needs and the expected corporate commercialization of space by flying groundbreaking research equipment in orbit never really evolved beyond preliminary experiments.

Nevertheless, four more Shuttle orbiters were built and delivered, all of which flew during the first half of the decade. Options for a fifth were agreed, with a full set of spares being fabricated in case of the loss of one of the vehicles and the need to build a replacement orbiter. Columbia (OV-102) flew the first four orbital flight tests (between 1981 and 1982) and the first operational mission on the fifth mission (also in 1982). She then flew the first Spacelab mission in 1983 and, after upgrades, the 24th mission in 1986. Former ground test vehicle Challenger (OV-099) was upgraded to replace Enterprise as an orbital vehicle, as it was found

|

Discovery OV-103 completes its first mission in space. |

to be too expensive to convert the latter vehicle after its ground tests. Between 1983 and 1985 Challenger completed nine missions, including three Spacelab missions, a number of satellite deployments, the first tests of the MMU, and satellite servicing of Solar Max. During 1983, the first American female (Sally Ride) and ethnic minority (Guion Bluford) astronauts also flew their first missions on Challenger.

In 1984, a new orbiter, Discovery (OV-103), was commissioned, followed the next year by Atlantis (OV-104). In a little over a year, Discovery supported a number of satellite deployment missions, satellite servicing-related EVAs, and the first dedicated DoD classified military mission. Atlantis was introduced in the fall of 1985 and completed a DoD mission on its first flight. Its second supported EVAs devoted to space construction demonstrations. By the end of 1985 not only had NASA astronauts flown on the Shuttle, but also representatives of the U. S. military, scientific and commercial payload specialists, political observers, and a number of astronauts from other nations, including Canada, Germany, The Netherlands, France, Mexico, and Saudi Arabia.

From 1986, there were plans to fly even more foreign payloads and crew members, to deploy space probes and space telescopes in the second half of the decade, and begin the initial flights in support of the creation of a large space station, called Freedom, which had finally been authorized by President Ronald Reagan in 1984 after years of debate, redesign, and deliberation. Space Station Freedom (SSF) would be created and operated by international collaboration between the U. S., Europe, Canada, and Japan and would be assembled by a series of Space Shuttle missions over several years.