Application by design

Using redirected lunar hardware, the Skylab space station became the first (and, to date, only) American domestic space station, another example of the long, complicated, and troubled American space station history within both NASA and the USAF. The military-orientated Manned Orbiting Laboratory program (utilizing a variant of the NASA Gemini spacecraft for crew transport) was canceled in 1969 after six expensive years of development and only one unmanned test flight. The NASA “civilian” space station program began quietly in the early 1960s, discarding the various grand plans revealed in the 1950s for giant stations circling the Earth and instead focusing upon creating payloads of scientific hardware flown on adapted Apollo spacecraft. These would supplement, but not replace, the lunar effort. Preliminary studies both within NASA and at contractor level revealed that the Apollo Command and Service Module, the Lunar Module, the Saturn family of launch vehicles, and the supportive hardware had the flexibility and potential to complete far wider missions than just sending men to the Moon for short visits to set up scientific instruments, return a few boxes of Moon rock, and plant a flag.

These ideas were soon identified as Apollo Extension (or Apollo X) missions. They were an obvious continuation to the basic lunar profile missions, which

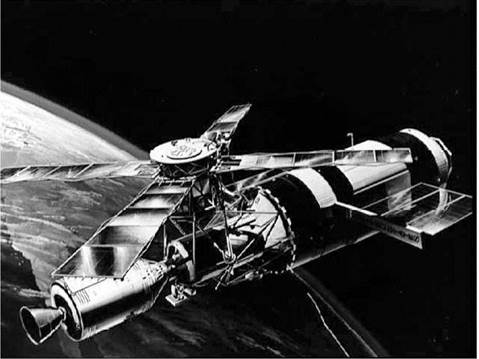

|

An artist’s impression of Skylab in orbit. |

could be flown throughout the late 1960s and into the 1970s or beyond. However, as the effort intensified to develop the hardware required to reach the Moon, hopefully before the Soviets, so too did the administrative and political pressure not to divert substantial funds away from the main Apollo lunar program. Any new program suggestions suffered accordingly. Indeed, there was so much focus on simply getting the men to the Moon and safely home that even the science intended to be conducted on the Moon was reduced to almost nothing for the first landing. This was of course partly because of the immense challenge in simply achieving the landing in the first place and a desire not to overcomplicate the first attempt. Any expansion of science could be deferred to later missions once the commitment to reach the Moon by 1970 (and beat the Soviets) had been achieved.

The studies continued, however, and in an attempt to mask their appearance as a “new start” the programs were restructured. In 1966, Apollo X and all its connotations were gathered under a new program branch, identified as the Apollo Applications Program (AAP) Office. The primary focus of this effort centered upon using spent Saturn launch vehicle stages fitted out in space as rudimentary space laboratories. There were other missions proposed, but the Orbital Workshop (OWS) concept was the flagship of the AAP program. The rocket stage intended

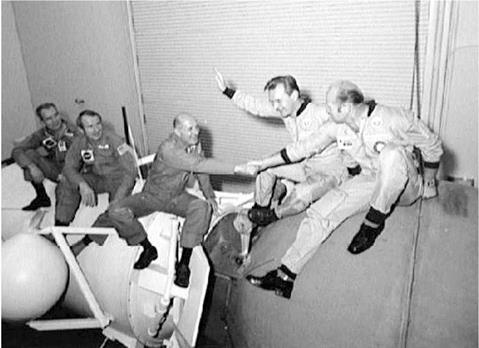

|

Early designs from the Apollo X studies.

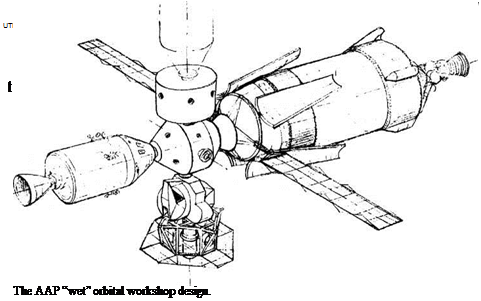

for use as the station would be fueled and used during the launch. Once in orbit and empty, it would be decontaminated by the crew, who would arrive in a CSM ferry craft. This became known as the “wet” workshop design. NASA had to be careful to avoid promoting the space station program as a new start because of the possible threat to the budget allocation for the mainline Apollo effort. The

way round this was to identify the “new program” (that was not officially new) as one that was simply applying the hardware and skills of Apollo to a range of further missions beyond the original remit.

Most of these missions were expected to fly in Earth orbit in between the lunar missions. After the initial Apollo landing missions (probably four or five), AAP missions to lunar orbit would follow, creating an OWS there followed by 14-day missions to the surface, hopefully setting up a small research base and extended surface expeditions. Unfortunately, concerns over the cost of the mainline Apollo and the decline in both interest and support for going to the Moon by both politicians and the public signaled the end of extensive AAP operations.

By the end of 1969, the lunar landing by Apollo had indeed been accomplished, twice, but only one AAP space station remained on the manifest. Three manned missions were planned, but it would not become the primary focus until after the Apollo missions to the Moon were completed. By early 1970, AAP had been renamed Skylab and the “wet” workshop design had also changed. Now, the laboratory would be launched on a two-stage Saturn V, with the third stage pre-fitted out as a fully equipped “dry”, or unfueled, workshop. The three teams of astronauts were planned to fly 28, 56, and 56-day missions during 1973.

Skylab 1, the unmanned laboratory, was launched in May 1973 and was almost lost during the attempt, with one of the solar power arrays and micrometeorite shields being ripped off by aerodynamic stress. Almost limping to orbit, the problems in cooling and powering up the station caused the first mission to be delayed to give NASA time to develop plans and hardware to recover the station to as near planned operating levels as possible. The success of the first and second crews in deploying the remaining array and installing protective solar shades saved Skylab, allowing a full three-mission program to be completed. The missions set new endurance records of 28 days, 59 days, and an impressive 84 days (both instead of the planned 56), rendering a potential 21-day fourth visiting mission unnecessary. The Skylab teams gained significant experience and gathered important results from Earth observations, solar studies, medical investigations, and a wide range of other experiments and research studies in materials processing, astronomy, and education.

Unfortunately, the fully functional backup laboratory, “Skylab B”, was not launched due to budget restrictions. Instead, the flight-ready module was sent to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D. C. for public display. To this day, former astronauts who could have flown to and lived in the station are reluctant to visit the display, recalling lost opportunities. Other unflown Apollo Saturn hardware from the canceled lunar missions was allocated to the Johnson, Marshall, and Kennedy Space Centers as museum pieces. This was very disappointing, not only for those who had built the vehicles and those who had hoped to fly on them, but also for those who had negotiated the funding to pay for them under the Apollo program. Instead they remained on the ground, stark reminders of what might have been.

Following Skylab, the only remaining American mission firmly on the launch manifest was the docking mission with a Soviet Soyuz, which was designated the

|

Skylab 4 commander Jerry Carr enjoys microgravity inside the orbital workshop. |

Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. This one-off mission occurred in the summer of 1975, when Apollo “18” rendezvoused and docked with Soyuz 19. The ensuing handshake in space between astronauts and cosmonauts as they opened the connecting hatches for the first time featured in the headlines around the world; a demonstration of growing detente between the two superpowers both on Earth and in space.

The ASTP had evolved from talks between representatives of the American and Soviet space programs in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with agreements on the exchange of data on both manned and unmanned missions. In early plans, it was suggested that an American Apollo might dock with a Soviet Salyut space station crewed by Soyuz cosmonauts. This was soon dismissed as impractical by the Soviets, since Salyut did not then have two docking ports. What was not revealed at the time was that a second-generation Salyut station was in development which did indeed feature two docking ports, a design which would not be revealed until later in the decade. Following the ASTP mission, talks continued for some years and included the possibility of docking a Shuttle orbiter to one of these, now revealed, second-generation Salyuts. Unfortunately, the political climate worsened, so talks on joint manned missions were abandoned for over a decade.

|

Publicity shot for Apollo-Soyuz crews (left to right): Slayton, Brand, Stafford, Kubasov, and Leonov. |