Off to the Moon

Sadly, the start of Apollo manned operations was marked by a tragedy, not in space but on the ground, with the loss of the Apollo 1 crew in a pad fire a couple of weeks before the planned Earth-orbiting mission. This set back the program almost two years, with the first crew not flying in an Apollo spacecraft until October 1968. It is also important to point out that there were other issues (with the qualification of the launch vehicles and reducing the weight of the Lunar Module) that further delayed the manned missions. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that the Apollo landing attempts would probably not have occurred before 1969, even without the Apollo 1 fire.

In December 1968, the Apollo 8 mission became the first to carry astronauts around the Moon. Occurring at Christmas time, it gave the chance for a significant worldwide audience to watch the TV transmissions from lunar orbit. Then, in March 1969, the Apollo 9 crew tested the bug-like Lunar Module (LM) in Earth orbit and evaluated the Apollo lunar suit in a short EVA. Two months later in May, Apollo 10 astronauts took the LM to nine miles above the lunar surface, clearing the way for Apollo 11 to make the first landing attempt. In July 1969 millions saw Neil Armstrong step into history, followed by Buzz Aldrin as the first humans to land, walk, and five on the Moon, if only for a few short hours.

Once Apollo started flying with astronauts on board, the missions for the rest of the decade progressed remarkably smoothly, given the complexity of the missions and what they were trying to achieve. This apparent ease of success contributed to a general impression in both the politicians and public that space flight was becoming commonplace and that flying to the Moon was routine. One mission would soon demonstrate how wrong that impression was.

Meanwhile, the Soviets, while watching Apollo grab the headlines, quietly resumed the Soyuz missions at about the same time that Apollo returned to flight after Apollo 1, prompting Western observers to erroneously suggest that the race to the Moon was back on. The primary goal of the first Soyuz missions was for the cosmonauts to gain experience of manned rendezvous and docking, something they had lost ground with to the Americans. After the failure of Soyuz 3 to dock with the unmanned Soyuz 2, there was a concerted effort to achieve manned ren-

|

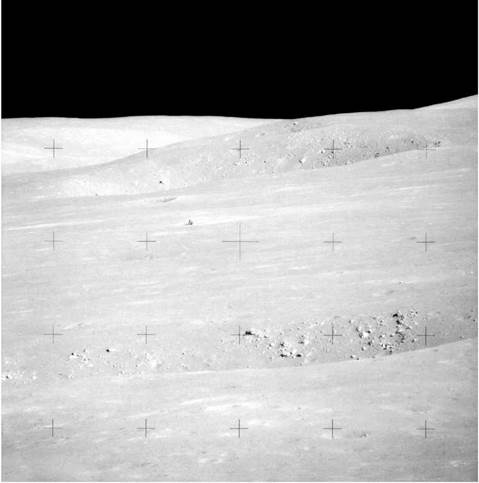

The Apollo Lunar Module sits on the barren lunar surface. |

dezvous and docking with another crew in a second spacecraft. This had been the original objective of Soyuz 1 and the canceled Soyuz 2 in 1967 and was finally achieved with Soyuz 5 linking up to Soyuz 4 in January 1969. Two of the cosmonauts also completed an EVA from Soyuz 5 to 4, returning in the second craft. At the time, this was promoted as the world’s first space station, but as more details emerged this bold claim was shown to be stretching the point a little. But it was still a significant achievement and a remarkable step forward for the Soviets.

Though not clear at the time, this was also a demonstration of the technique planned (but never demonstrated) for the Soviet lunar program, in which a lone cosmonaut would have spacewalked from the main craft to the lander and later, after returning from the Moon, would have completed a second EVA to enter the return craft for the trip home. Unfortunately, when the feat was tried again (this time without an EVA planned), Soyuz 8 could not dock with Soyuz 7. Both vehicles did compete a group (troika) flight with Soyuz 6 in which the first space welding experiments were performed, but it was another bitter blow to the Soviets in the wake of the success of Apollo 11 and the failure of their unmanned Luna 15 sample return craft. It lent credence to the argument for abandoning the Moon to the Americans and pressing on with creating a space station in Earth orbit instead, some years before the planned U. S. Skylab station was launched.

Shortly after the Soyuz troika flight came Apollo 12, which repeated the success of the previous Apollo missions by landing on the Ocean of Storms. Pete Conrad and A1 Bean conducted two Moon walks to deploy a suite of surface experiments and then visited the unmanned Surveyor III which had landed nearby some 30 months earlier. Unfortunately, a failed TV camera did little to help viewer ratings back home with the audience having to hear what the two astronauts were doing instead of watching their activities.

Plans for Apollo originally included at least 10 landings, followed by the creation of a rudimentary space station, cleverly constructed from elements of Apollo/Saturn hardware. It was hoped that more extensive lunar exploration missions and further Saturn workshops would be launched, leading to far larger space stations by the 1980s. These were expected to be crewed by up to 50 astronauts and supplied by a reusable space ferry called a “space shuttle”. By the 1980s, Apollo-derived hardware could be used to send the first humans to the planet Mars. This was the grand plan in 1969.

One of the major stumbling blocks in securing this grand vision was the April 1970 mission of Apollo 13. The explosion suffered on the way to the Moon aborted the planned landing and almost claimed the fives of the crew. The dramatic recovery of the three astronauts after such a perilous journey around the Moon and back home passed into NASA lore. It showed the agency at its very best at a time of great difficulty. Unfortunately, the seeds of success with Apollo were also maturing to throttle its future at the height of its accomplishments. NASA astronauts had reached the Moon within the timescale that President Kennedy had proclaimed and had achieved the feat twice. But now the American public was questioning why there was any need to keep going back when there was no sign of competition from the Soviets or anyone else, there were so many difficulties at home, and there was a very costly conflict on the other side of the world draining American resources.

In the firing fine of all this was Apollo and the grand plan for what was to follow. Budgets had been tight for a while and, with new President Richard M. Nixon in office, were about to become much tighter. The first casualty was Apollo 20, which was canceled in January 1970, with the remaining seven flights stretched out over the next four years. In September 1970, five months after nearly losing Apollo 13, two more flights were canceled. Apollo would now end with flight 17 and, following the lunar flights, only one Saturn workshop (now called Skylab) would fly instead of the planned two or three. There would be no series of extended lunar missions or Apollo’s flying in Earth orbit to utilize the skills gained and hardware proven for other objectives. On a more positive note, although they had lost the so-called “race” to the Moon, relations between the Soviets and the U. S. had improved and plans were being developed to fly a joint docking mission with cosmonauts during the mid-1970s. There were also signs that the Space Shuttle might still be authorized, although the large space stations it was originally planned to service were struggling to find support and funding. Any mention of manned missions to Mars was quietly dropped.

By the time the Soyuz troika missions flew in October 1969, Apollo 11 had won the race to the Moon for the Americans, while Soviet manned lunar hardware had still to leave the ground. The final blow for Soviet manned lunar exploration had been dealt and the leadership was planning a shift towards mastering long-duration space flight. They still held out hope for lunar success until 1974, when the lunar effort was finally abandoned. A major stepping stone in support of the space station goal, however, was the highly successful 18-day Soyuz 9 mission, flown in June 1970, the final mission flown in the first decade of manned space flight. It was an indication of things to come, looking to extend the duration of human flights in space rather than sending them out to explore distant worlds, at least for the near future.