Preparing for the Jets

By this point, in the mid-1950s, excitement and anticipation for the coming jets was rising to a fever pitch. The mass media was awash in colorful ads touting the new generation of jet airliners about to take to the skies. You couldn’t pick up a copy of Reader’s Digest, National Geographic, LIFE, Look, or Collier’s without seeing myriad ads from Boeing, Douglas, and Convair extolling the exciting virtues of commercial jet travel. Images usually included swept-wing shapes with white contrails against a dark blue sky, and maybe even a full moon thrown in for dramatic effect. A smooth ride, quietness, and above all, speed, were always the featured highlights of these ads with lots of young kids shown gazing wide-eyed at tall, handsome airline captains and their new jets.

From an operational standpoint, however, airline and airport managers were grappling with the unknown. Although both Los Angeles and New York had plans for big jetports on the drawing board in 1955 for LAX and Idlewild, both facilities were still years away from having 10,000-foot-long runways, modern roomy terminals with fully enclosed jet bridges, and acres of bright new concrete ramp space. Airline planners were trying to cope with how they could best integrate the monstrous smoke-spewing jets among tightly grouped DC-6s, -7s, Connies, and Convairs parked next to a terminal building like so many cattle waiting in a stockyard. The jets’ larger wingspans and exhaust blasts alone were cause for concern, and soon, contingency plans were formulated to park and service the jetliners at the very end of boarding concourses, safely away from the prop aircraft, if for nothing else, ease of operations.

Yes, the promise of swift five-hour coast-to-coast flights and luxury travel in the stratosphere was certainly enticing to the traveling public and aircraft enthusiasts alike. However, the cold prickly reality of how to incorporate these fire-breathing machines with their passenger loads of twice the norm into existing airport infrastructure was daunting. In studying the specific problems the new jets would represent, it was quite evident that a

|

|

|

|

|

|

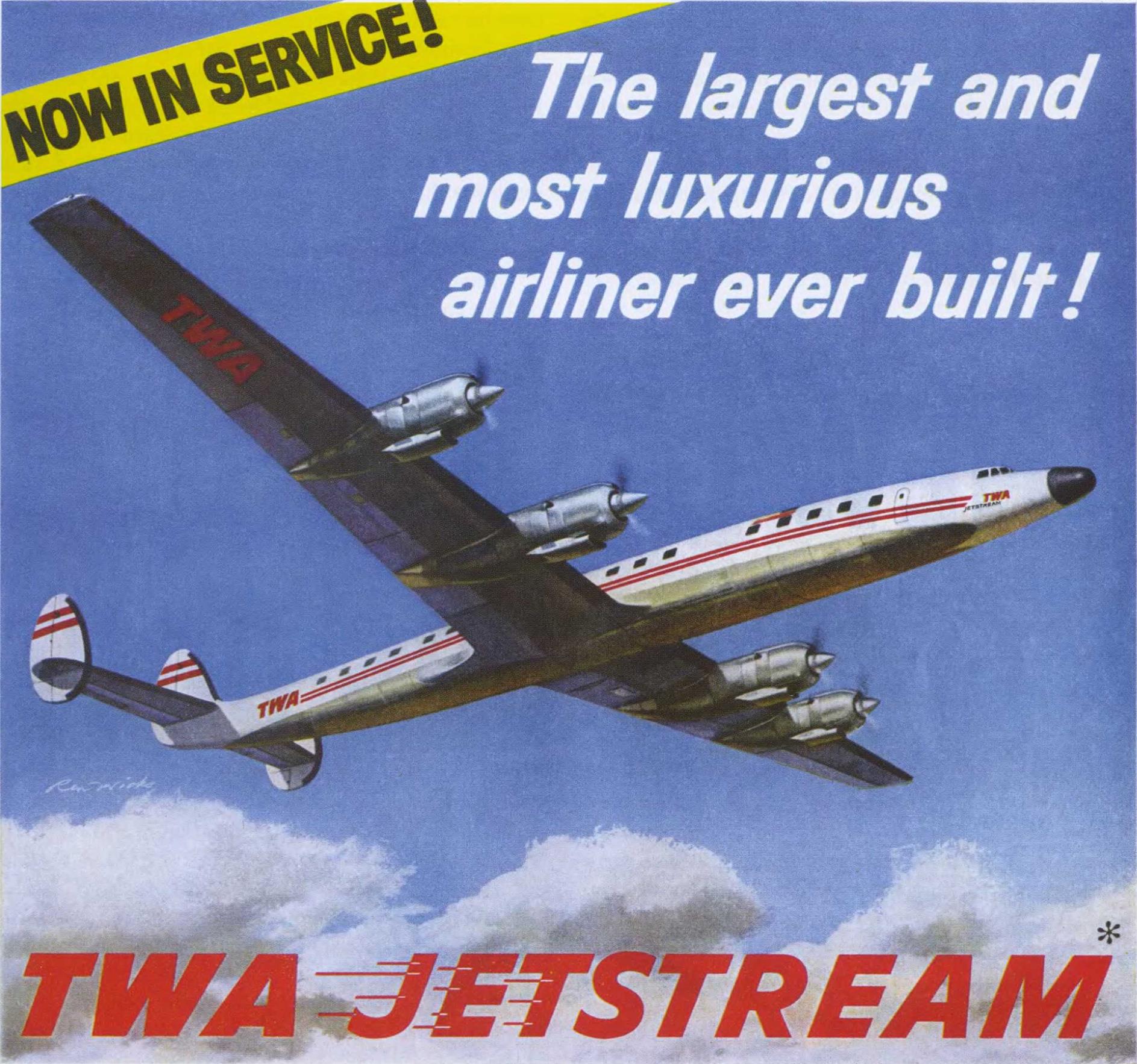

As anticipation for the next generation of transports continued to build with the traveling public in the mid-1950s, just using the word "jet" somehow seemed to bring the new air age closer. Enter the Jetstream Constellation in 1957, better known as Lockheed’s Model 1649A Starliner. Los Angeles illustration icon Ren Wicks worked for Howard Hughes painting everything from movie posters to airline ads. For this 1649 image, Hughes specifically asked him to exaggerate the aircraft’s wingspan and distance of the engines outboard from the fuselage. Here is the result! (Mike Machat Collection)

new paradigm in airport design and aircraft operations would be required to cope with the pending onslaught of new commercial jetliners. Until that happened, however, jets and props would have to be operated in a “best of both worlds” environment. To paraphrase the famous line from Dickens, “It was the best of times” for the final generation of propliners, and “the worst of times” realizing the jets were coming, and not being quite ready to cope with the expected changes.