The 367-80: Boeing’s $15 Million Gamble

First, as previously noted, the de Havilland Comet entered service in May 1952, but was subsequently grounded within two years, after its infamous series of accidents. Second, Boeing froze the design for its new “prototype jet transport” into a sleeker configuration with four jet engines, each in their own separate underwing nacelle, a stubbier vertical fin, and a more airlinerlike cockpit design. Disguised with a deceptive “Model 367” designation (used internally by the company for its KC-97 military tanker/transport version of the Stratocruiser), this larger, faster, and more powerful design was the eightieth configuration considered. Hence, the official name for Boeing’s new jet prototype became the 367-80.

Constructed in a special walled-off and highly secure area of Boeing’s historic Renton, Washington, facility, the “Dash 80” was built in only 18 months, and was rolled out for Boeing employees and industry representatives

on May 15, 1954. This one-of-a-kind proof of concept demonstrator was unlike any other airplane ever seen at that time. Painted in a striking school-bus-yellow and chocolate-brown color scheme, the jet was 128 feet long with a 130-foot wingspan and a tail height of 38 feet. The engines were Pratt & Whitney’s new J57 turbojets, and the airplane’s main landing gear sported four wheels on each side instead of the traditional two. Anyone who saw the Dash 80 knew it was something special. What they didn’t know was that this airplane would change air travel forever by siring an entire family of jet transports that would reduce travel times between any two places on earth by a staggering 50 percent.

Christened by Mrs. William Boeing as the “airplane of tomorrow,” the 367-80 soon underwent preparation for its first flight. After a series of rigorous systems checks and taxi tests, the giant craft lifted off from Renton’s runway for the first time on July 15, 1954,

piloted by Boeings Chief Test Pilot, A. M. “Tex” Johnston. The unique thing about that first flight is that there had been no airline orders placed for the airplane whatsoever. Not one! Then, as the new prototype began to demonstrate what a large jet-powered transport could do, the world began to take notice. So did the United States Air Force, which was in dire need of a faster aerial-refueling aircraft to service its new fleet of jet-powered strategic bombers and tactical fighters just then entering the inventory.

Boeing quickly “put its money where its mouth was” by flying the Dash 80 on a series of impressive demonstration flights, taking any number of special industry guests and aviation luminaries for their first rides in a jet-powered aircraft. Names like USAF Chief of Staff, General Curtis LeMay soon graced the passenger roster as he evaluated the airplane for its impending role as the Air Force’s new “flying gas station,” to be known as the КС-135 Stratotanker. Excitement was building around the new jet, as the publics anticipation of flying in America’s first jet airliner grew in magnitude. The Dash 80 was catapulted to national attention when Tex Johnston performed not one, but two barrel rolls while flying over the famed Gold Cup speed-boat races at Seattle’s Sea Fair in August 1955. Asked later by Bill Boeing why he did it, Johnston replied in his typical droll manner, “I was selling airplanes.”

On one memorable demonstration flight, Johnston was told by the Boeing Field tower to remain in position on the ramp with engines running. It was a typical rainy spring day in Seattle, and Tex noticed a company car racing out to the airplane. Emerging from the back seat was a tall, slim figure clutching his raincoat tightly to his body. Rushing up the boarding stairs, the gentleman walked into the cockpit and unceremoniously took his place in the airplane’s jump seat. Tex turned around to greet him, and shook hands with none other than Charles A. Lindbergh, acting in an advisory capacity for Pan American World Airways. According to Johnston, Lindbergh later sat in the co-pilot’s seat and even took the controls of the Dash 80 while flying over Portland, Oregon, at 600 mph. Johnston marveled at how much aviation progress had been made in the less- than-thirty-year time span since Lindbergh’s epic solo transatlantic flight in 1927!

On October 16, 1955, with William Boeing and other VIP guests on board, Johnston flew the Dash 80 from Boeing Field in Seattle to Washington D. C., reaching a top speed of 620 mph and arriving at Andrews Air Force Base in only 3 hours 48 minutes. The fact that this flight established a new U. S. coast-to – coast cross-country record did not go unnoticed by the world’s airlines, and orders for a slightly larger production version of the new jet, called the 707, started coming in to Boeing in impressive numbers.

Boeing’s first airline order was from Pan American when its President, Juan Trippe, ordered 20 of the new jets. American’s C. R. Smith ordered 30, and then came Continental and Braniff orders. Surprisingly, the first foreign air carrier to order the 707 was Belgium’s Sabena, followed by Air France. Bringing up the rear in this initial batch was TWA with its pivotal order for 8 of the new jetliners, bringing the total 707 order book to 81 airplanes. Although this will be covered in more detail later, it should be mentioned that by this time, rival manufacturer Douglas Aircraft, still king of the airliner builders, had recorded 124 orders for its similarlooking, but yet-to-be-flown DC-8 Jetliner.

For awhile, it appeared that Boeing would never be able to break the decades-old stigma of being in Douglas’s shadow as an airliner builder, but when BOAC, Lufthansa, El Al, and Air India lined up to order longer-range versions of the 707, Boeing’s tally grew to 145 before the DC-8 ever flew, and the race was on. As we will see later, both of these jetliners evolved into larger and more improved airplanes, but once Boeing gained the advantage and pulled ahead of Douglas, there was no turning back. With its Dash 80, Boeing literally “bet the company” that this revolutionary new aircraft would eventually become a commercial success, and it will be considered for all of history to be one gutsy $15 million gamble that paid off quite handsomely.

|

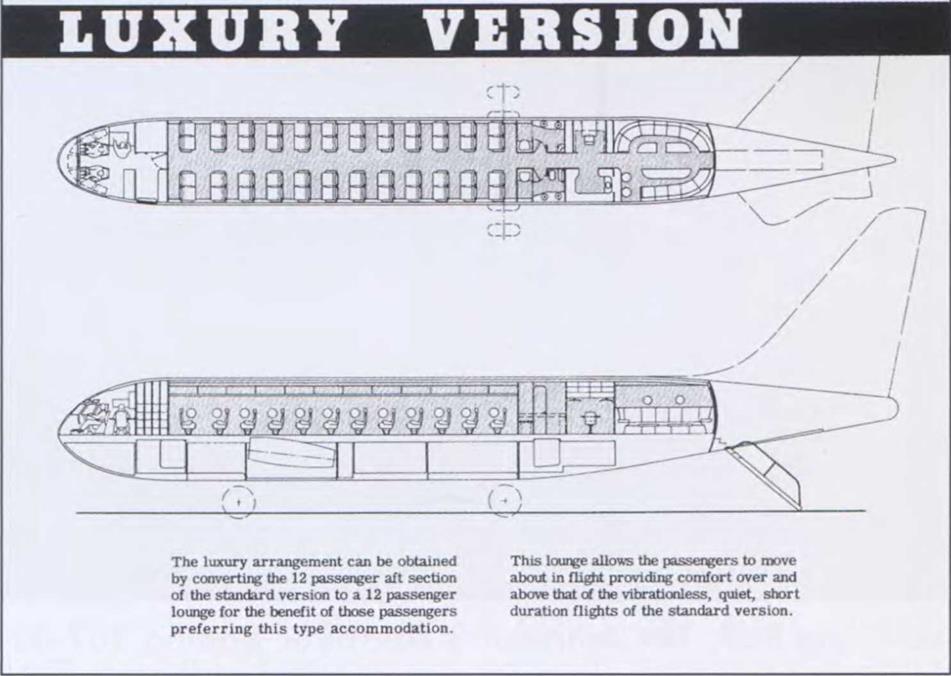

mercial jet travel would be like for the privileged passengers who would someday fly aboard a later production version of the airplane. As with any radical new design, countless engineering studies resulting in numerous aircraft concepts are winnowed down to a smaller number of final configurations from which the actual prototype design is chosen. Emerging from this design process in October 1950 was the Boeing Model 473, an airliner featuring a double-lobed and truncated Stratocruiser-type fuselage. Swept and tapered vertical and horizontal stabilizers from the B-47 were mounted on the rear fuselage, while double-podded engines were slung from its swept wing at mid-span, one pod per side. Similar in size to the largest DC-7s and Constellations of the time, this distinctive new design looked arresting to the casual viewer but somehow appeared “not quite ready for prime time.” Conceived from the outset as more of a marketing study than an actual “hard” design concept, the 473 was to have a gross weight of 135,000 pounds and a cruising speed of 500 mph at 40,000 feet. This was unheard-of performance for its day, especially with Britain’s Comet still two years away from entering passenger service. Cargo capacity of the 473 was to be 5,000 pounds distributed in two separate lower-fuselage baggage compartments, one fore and one aft of the wing. Powerplants were to be four unspecified turbojets in the 9,500-pound-thrust category, and with its military – type drag chute, the airplane was intended to be able to operate from existing runways at any major airport in the world. By 1954, however, two major developments had a profound effect on the future of commercial air travel. |

|

This airplane’s shape didn’t just suggest the Jet Age, it was the Jet Age. With design features such as a rakish 35-degree swept wing and podded turbojets lifted directly from Boeing’s new B-47 strategic bomber, the Model 367-80 prototype, or “Dash 80” as it came to be known in industry circles, epitomized jet travel, and left Britain’s formerly cutting-edge de Havilland Comet in the dust. Cruising high in the stratosphere at almost transonic speed, the Dash 80 symbolized what com- |

|

mORE RULES PER HOUR CREW, INSURANCE, DEPRECIATION ENGINE, AIRCRAFT |

|

This chart graphically shows the fuel cost and time advantage of the Model 473 over existing propeller – driven airliners. Although this particular airplane was never produced, the writing was on the wall for a new generation of jet-powered transports to take the airline industry to its next level. (Craig Kodera Collection) |

|

Artist’s rendering of the Model 473 in flight shows the influence of Boeing’s С-97/Stratocruiser with its similarlooking nose section and double-lobe fuselage. Engine pod design was lifted directly from the B-52 Stratofortress. (Craig Kodera Collection) |

|

Model 473 Inboard Profile shows the passenger cabin arrangement to best advantage. Considering that airliners of this time period carried a payload of about 50 passengers, this concept must have seemed gigantic by comparison. (Craig Kodera Collection) |