Explorer III data acquisition

The first recordings of the Explorer III low-power telemetered data were obtained near the end of the first orbit by the JPL, Earthquake Valley, and Temple City Microlock stations, beginning at about 19:38 UT on 26 March. The next pass (pass 2) provided useful data at about 21:40 UT from Temple City. Pass 3 was received at Temple City at about 00:37 UT on 27 March, and Patrick Air Force Base (PAFB) received it a short time later. For the next five orbits, the satellite passed out of range south of the Microlock stations, and low-power telemetered data were not obtained. But when the orbit passes reappeared over the United States, Temple City immediately recorded a long 15 minute pass beginning at about 12:25 UT, and PAFB received the signal a short time later. And so it continued, with the Microlock stations receiving useful low-power data during essentially every orbit that carried the satellite over their locations.

A complete tabulation of the low-power continuously transmitted data similar to that for Explorer I was never assembled. Although the low-power data were used at JPL for engineering assessment, at Cambridge for the micrometeorite data, and for cursory examinations of the cosmic ray data, the primary focus of the data analysis efforts in our laboratory quickly turned to the tape recorder dumps telemetered by the high-power system.

The high-power system was completely new with Deal II. The satellite transmitter was turned on by ground command, and it remained on only long enough to transmit the data that had been stored on the onboard recorder since its previous readout. Typically, for a dump of the data from a full orbit of recording, the transmitter was turned on, the tape readout began after about two seconds, and it lasted for about six seconds. The transmitter was turned off by the onboard programmer immediately after completion of the readout to conserve battery power.

The first attempts to recover the onboard-recorded data from Explorer III were disappointing, as described earlier. It was not until I arrived in Huntsville the day after the launch that I was able to get an encouraging summary of the first 11 passes from Jack Mengel in Washington. There were at least hints of proper operation of the complete system during passes 2, 4, 6, 7, 10, and 13.11 It was only shortly after that, a full day after launch, that anything approaching the expected performance was achieved. On pass 14, Quito, Ecuador made the first completely successful singlecommand interrogation that resulted in the successful recording of data that had been accumulated over a full satellite orbit. That result was achieved increasingly as the stations became more proficient.

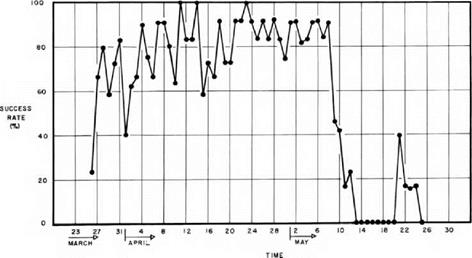

During the 44 day period of normal operation of the onboard storage and readout system, the satellite completed 523 orbits, and recorder interrogations were attempted

|

|

||

|

on 504 of them. Of those, 408, or 81 percent, resulted in useful data. The success rate was only about 23 percent on the first day but climbed steadily throughout the operating lifetime. By the third day of operation, the average daily success rate reached about 80 percent, and by the end of the operating lifetime, the rate was consistently averaging more than that figure. The interrogation success rate for the entire operational period is shown graphically in Figure 11.2.

There were several reasons for the disappointing initial performance. In the first place, this was the first use of the ground station command transmitters, and it took some time for the operators to resolve equipment issues and to fine-tune the procedures. Adding to the problem was the fact that the high-power system used a completely different and more complex operational mode than had been used for both the low – and high-power systems on Explorer I, and for the low-power system on Explorer III. After the interrogation command was transmitted, the responding data flow began after only two seconds. Thus, all equipment had to be pretuned, and the ground tape recorder had to be running before the command was sent. It took time for the operators to become proficient in this new and somewhat complex operation.

A second problem aggravated the data acquisition problem. It took time for the Vanguard Computing Center to accumulate enough tracking data to produce orbital predictions accurate enough to prealign the antennas. Since the entire high-power operation had to take place in a matter of seconds, there was no time to realign the

|

CHAPTER 11 • OPERATIONS AND DATA HANDLING

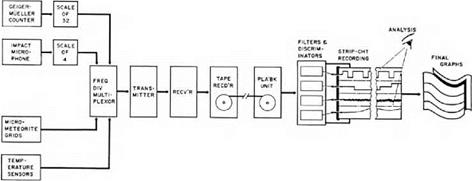

FIGURE 11.3 Greatly simplified diagram showing the flow of data forthe low – and high-power system on Explorer I, and for the low-power system on Explorer III. There were minor differences in the sensor complements on those systems. The sensors, scalers, multiplexers, and transmitters shown in this drawing were located in the satellites. The receivers and ground tape recorders were located at the tracking and data acquisition stations. The break between the tape recorder and playback unit represents tape shipment, quality control, and tape duplication. The playback unit and the rest of the equipment were located in the physics building at the University of Iowa. |

antenna if it had not been properly preset. By the end of the first day, the orbital prediction accuracy improved, thus contributing to the improved data recovery.