A heartbreaking failed launch attempt

A satellite launch operation was (and remains today) a carefully choreographed ballet, with dozens of key performers and hundreds of supporting personnel. The common

|

CHAPTER 10 • DEAL II AND EXPLORERS II AND III 273

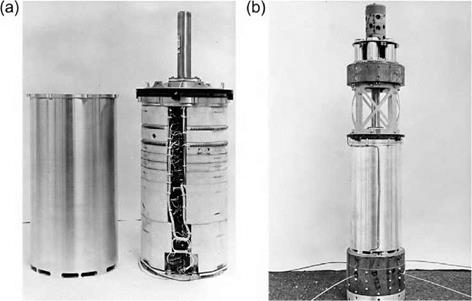

FIGURE 10.4 The completed Explorer II (Deal Ila) satellite payload. (a) The cosmic ray instrument is exposed beside its cylindrical housing. The GM counter protrudes from the top. (b) The fully stacked satellite payload, with its outer shell and cone removed to show the complete structure. The cosmic ray instrument cylinder is mounted atop the bottom antenna insulator gap. The low-power assembly, with its antenna gap, ring of batteries, and central electronics stack, appears above the GM counter. The aluminum ring at the bottom of the lower antenna gap served as the threaded attachment to the fourth rocket stage. Explorer III (Deal IIb) looked the same, except that the antenna whips at the bottom were eliminated. (Courtesy of NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute ofTechnology.) |

media portrayal of countdowns, with their final “three-two-one” and terse “liftoff,” is the climax of an extremely long and arduous process. Each tiny action is minutely defined, timed, and documented ahead of time, and many detailed lists of steps (countdown lists) are assembled and pretested. Each such list terminates in a go/no – go decision, and all lists are linked to form the whole. For the Deal II launch there were, in addition to the master countdown conducted by the launch director in the blockhouse, separate countdowns for activating the blockhouse, activating the launch pad, activating each of the rocket subsystems, fueling, and so on. Closer to my own area of activity, there were countdowns for the final preparation of the satellite instrument package, for attaching it to the final rocket stage, for activating the backup Spare Payload in case it was needed at the last moment, for readying the Microlock ground station, for activating the interrogation ground transmitter, and so on. Just one, the countdown list for preparing the payload for its mating to the final rocket stage, occupied a number of pages.

OPENING SPACE RESEARCH

![]() For rocket launches until the time of the later, much more massive Saturn 5 Moon rockets, the launch activities were centered in blockhouses near the pads. Those were an outgrowth of simple barriers used during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s to protect launch crews from possible explosions and other mishaps. The blockhouse used for the Jupiter C launches was representative of those employed during that period. It was located only a few hundred feet from the launch pad so that the two sites could be coupled through conduits and tunnels by hundreds of wires carrying power, control, and monitoring signals.

For rocket launches until the time of the later, much more massive Saturn 5 Moon rockets, the launch activities were centered in blockhouses near the pads. Those were an outgrowth of simple barriers used during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s to protect launch crews from possible explosions and other mishaps. The blockhouse used for the Jupiter C launches was representative of those employed during that period. It was located only a few hundred feet from the launch pad so that the two sites could be coupled through conduits and tunnels by hundreds of wires carrying power, control, and monitoring signals.

The blockhouse was dome shaped, with a very thick concrete and earth-covered shell to protect against direct impacts of wayward rockets. It was sealed against liquids and fumes in case the rocket’s load of fuel should spill on its top and ignite. Massive blast doors were sealed before liftoff, and the heating and air-conditioning systems were closed off from the outside world. The entire complex was switched over to internal electrical power generators to guard against failure of the main Cape Canaveral power or severance of the supply lines. The blockhouse was as nearly self-sufficient as it was possible to make it.

As the director of Von Braun’s Launch Operations Laboratory at Cape Canaveral, Kurt Debus served as the launch director for ABMA launches during that period. For the Deal II launch, he was at his usual station in the blockhouse, where he could have eye contact with all of the senior engineers at their separate launch consoles. He was one of the few who could actually see the rocket through one of the periscopes that poked through the roof of the blockhouse. For this launch, Von Braun was at his favorite blockhouse observation post, with his own periscope. I was located in the rear of the blockhouse at a rack of equipment that received and displayed the signals as they were received from the satellite payload. We were all able to switch our earphones between several special telephone and intercom circuits. One permitted those of us monitoring the instrument to talk to crews at the Microlock receiving station in its trailer some distance away, to the RIG site where the command transmitter was located, and to other locations. A narrator kept all apprised of progress via a public address system.

Unlike the Deal I situation, I was fully integrated into the prelaunch activities for Deal II. Of course, the JPL payload manager had the overall responsibility for the satellite payload, but I was directly involved in all decisions dealing with the performance of the cosmic ray instrument. I monitored every step of the payload assembly and checkout, performed numerous counting rate checks, and read and evaluated the many tape recordings of our instrument’s signals.

My journal entry at 4:20 AM on 5 March 1958 stated:

Have the [blockhouse] equipment turned on. Payload activation in 40 minutes. Sky is light cloudy and broken—rather high. This is the day for which I have been working since January

CHAPTER 10 • DEAL II AND EXPLORERS II AND III 275

1956. If successful, this is to provide my Ph. D. dissertation. I’ll have to give that payload a

goodbye pat.10

There were some difficulties during the countdown. At a check at X – 300 minutes, the onboard tape recorder double-stepped. That is, for each drive pulse, the recorder tape advanced two steps. All later operation was normal in that regard.

The most serious problem was the difficulty in commanding playback of the tape recorder during the final countdown. When spin-up of the upper rocket stages was started at X – 11 minutes, the recorder operated normally. But when the spin rate reached 550 rpm, we were unable to command playback. The launch director interrupted the spin-up, slowed the rotating tub, and then had its rate increased gradually. Playback was successful at 450 rpm but not at 500.

All of that occurred within the final few minutes of the countdown, while the rocket sat there fully fueled and ready to go. The pressure for a final go/no – go decision was intense, as further delay would have meant canceling the launch for that evening and recycling for the following day or later. While we held up the launch for 18 minutes, the payload manager, other payload engineers, and I had a lively discussion and concluded that the problem was with the on – pad commanding link, not with the recorder itself. Specifically, we believed that there was a problem with the grounding path for the interrogating signal and that operation would be normal once the rocket was free of the cluttered pad environment. I gave my go-ahead based on that assessment, and the countdown continued.

The official launch time was 1:28 PM EST on Wednesday, 5 March 1958. At my post in the blockhouse, I monitored the signal from the cosmic ray counter until it faded out downrange.

Later analyses indicated that the firing of stages one, two, and three were all normal. However, the fourth stage apparently failed to ignite, for reasons that were never completely determined, and the launch attempt failed. The satellite payload plummeted into the Atlantic Ocean about 1900 miles downrange from Cape Canaveral.11

As the payload passed over the island of Antigua, British West Indies, that station attempted to interrogate the onboard tape recorder to reset the tape to its starting point in preparation for the first orbit. That interrogation attempt failed to elicit a response. We were never able to ascertain whether that was because of a failure of the onboard instrument, a problem with the ground station, or the result of some catastrophic failure of the final rocket stage.

Even though it did not go into orbit, the payload received an Explorer II designation.

OPENING SPACE RESEARCH