Apollo and History

The set of judgments that led President John F. Kennedy to decide to send Americans to the Moon combined lasting characteristics of the American people, a conviction of American exceptionalism and a mission derived from that conviction, the geopolitical situation of early 1961, and the individual values and style that Kennedy brought to the White House. Apollo was a product of a particular moment in time. Apollo is also a piece of lasting human history. Its most important significance may well be simply that it happened. Humans did travel to and explore another celestial body. Apollo will forever be a milestone in human experience, and particularly in the history of human exploration and perhaps eventual expansion. Because the first steps on the Moon were seen simultaneously in every part of the globe (with a few exceptions such as the Soviet Union), Apollo 11 was the first great exploratory voyage that was a shared human experience—what historian Daniel Boorstin called “public discovery.”30 John Kennedy’s name will forever be linked with those first steps. Like other ventures into unknown territory, Apollo may not have followed the best route nor have been motivated by the same concerns that will stimulate future space exploration. But without someone going first, there can be no followers. In this sense, the Apollo astronauts were true pioneers.

|

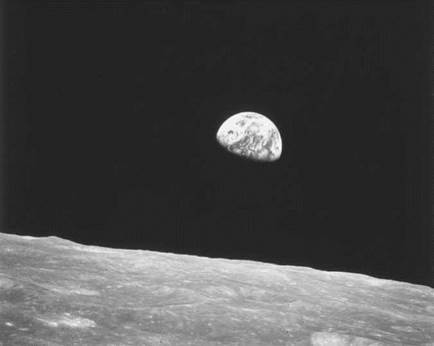

The iconic “Earthrise” picture taken on Christmas Eve 1968 by Apollo 8 astronaut Bill Anders as he and his crewmates became the first humans to orbit the Moon and to look back at their home planet from 240,000 miles away. (NASA photograph). |

Leaving the Earth gave the Apollo astronauts the unique opportunity to look back at Earth and to share what they saw. The Apollo 8 “Earthrise” picture is surely one of the iconic images of the twentieth century. It allowed us, as poet Archibald McLeish noted at the time, “to see earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats” and “to see ourselves as riders on the earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold—brothers who truly know that they are brothers.”31 That perception alone cannot justify the costs of going to the Moon, but it stands as a major benefit from going there, one that has influenced human behavior in many ways.

I hope that sometime in the future—if not in the coming decades then in the coming centuries—humans will once again choose to venture beyond the immediate vicinity of Earth. I believe that the urge to explore—to see what is over the next hill—is a fundamental attribute of at least some human cultures. Michael Collins, the Apollo 11 astronaut who remained in orbit as Armstrong and Aldrin experienced being on the Moon, has commented that the lasting justification for human space flight is “leaving”—going away from Earth to some distant destination. As future voyages of exploration are planned, I also hope that the United States chooses to be in the vanguard of a cooperative exploration effort involving countries from around the globe. There are two things I judge as certain, whenever those voyages take place. One is that they will not be like Apollo, a grand but costly unilateral effort racing against a firm deadline to reach a distant and challenging goal. The other is that President Kennedy’s name will be evoked as humans once again begin to travel away from Earth. As he said in September 1962, “We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people.” John F. Kennedy, like the astronauts who traveled to the Moon during Apollo, was a true space pioneer.

[1] have asked Jim Webb, Dr. Wiesner, Secretary McNamara and other responsible officials to cooperate with you fully. I would appreciate a report on this at the earliest possible moment.

[2] “The pace at which the manned lunar landing should proceed, in view of the budgetary implications and other considerations,” and

2. “The approach that should be taken to other space programs in the 1964 budget, i. e., should they as a matter of policy be exempted from or

[3] think the President had three objectives in space. One was to ensure its demilitarization. The second was to prevent the field to be occupied to the Russians to the exclusion of the United States. And the third was to make certain that American scientific prestige and American scientific effort were at the top. Those three goals all would have been assured in a space effort which culminated in our beating the Russians to the moon. All three of them would have been endangered had the Russians continued to outpace us in their space effort and beat us to the moon. But I believe all three of those goals would also have been assured by a joint Soviet-American venture to the moon.

The difficulty was that in 1961, although the President favored the joint effort, we had comparatively few chips to offer. Obviously the Russians were well ahead of us at that time. . . But by 1963, our effort had accelerated considerably. There was a very real chance we were even with the Soviets in this effort. In addition, our relations with the Soviets, following the Cuban missile crisis and the test ban treaty, were much improved—so the President felt that, without harming any of those three goals, we now were in a position to ask the Soviets to join us and make it efficient and economical for both countries.7

[4] think the President had three objectives in space. One was to ensure its demilitarization. The second was to prevent the field to be occupied to the Russians to the exclusion of the United States. And the third was to make certain that American scientific prestige and American scientific effort were at the top. Those three goals all would have been assured in a space effort which culminated in our beating the Russians to the moon. All three of them would have been endangered had the Russians continued to outpace us in their space effort and beat us to the moon. But I believe all three of those goals would also have been assured by a joint Soviet-American venture to the moon.

The difficulty was that in 1961, although the President favored the joint effort, we had comparatively few chips to offer. Obviously the Russians were well ahead of us at that time. . . But by 1963, our effort had accelerated considerably. There was a very real chance we were even with the Soviets in this effort. In