The Diminishing Role of LBJ and the Space Council

On April 20, 1961, President Kennedy asked Johnson, as chairman of the Space Council, to carry out a survey of the status of the space program. Johnson did indeed take charge of the review, but on a highly personal basis. There were no formal meetings of the National Aeronautics and Space Council before Johnson forwarded the May 8 Webb-McNamara recommendations to Kennedy with his endorsement, and in the April-May 1961 time period, there was only one Space Council staff person, executive secretary Edward Welsh.

Kennedy made the final decision to approve the recommendations of the Webb-McNamara report and to announce them before a joint session of Congress while the vice president, at Kennedy’s request, was traveling in Asia. The absence of Johnson during this critical period was symbolic of his declining role after May 1961 as the first among equals with respect to advising the president on NASA’s programs. It is very likely that Johnson’s urging Kennedy to approve a major acceleration of the civilian space program was an important influence on JFK’s decision to go to the Moon. However, once Kennedy had made the basic decision, he relied primarily on his White House policy, technical, national security, and budgetary staff and on the NASA leadership to provide him information on the implementation of that decision and to relay his concerns and decisions to the NASA workforce. Kennedy soon realized that what he was likely to get from Johnson and the Space Council staff was unquestioning advocacy for a strong space effort, not the kind of dispassionate analysis that he most welcomed. Science adviser Jerome Wiesner and his staff and David Bell and his BOB staff thought it was their role, whatever their personal views, to raise questions about the choices NASA was making with respect to various aspects of the space effort. The predictability of the positions that Lyndon Johnson and the Space Council staff would take on most space issues limited their influence on Kennedy’s policy choices.

Thus—with one important exception, developing during 1961 the administration’s approach to bring communications satellites into early practical use—the Space Council as a body was not central to any of the civilian space decisions of the Kennedy administration. James Webb characterized the council’s role as different from “the popular image that the president had turned everything over to the vice president” with respect to space; that was “simply . . . not true.” Rather, Kennedy “wanted to control the agenda of the council” and did not want “to abandon the normal budgetary process by having the Space Council make the space budget.” On the other hand, Kennedy was “very happy” to have Johnson “to take the lead in talking about things and making speeches and participating actively in carrying out things that the president decided he wanted.” Johnson may have wanted “different instructions” from Kennedy about his responsibilities for the space program, but in practice Webb “never saw him go beyond what Kennedy had indicated he wanted done.”5

In his role as chairman of the Space Council, Vice President Lyndon Johnson “appeared to take his duties seriously, even if his responsibilities were only advisory and minimal.” Johnson had originally hoped that the budget for the Space Council staff would be $1 million; “the bigger the budget, the bigger empire Johnson could build.” But Congress, sensing “that Johnson’s role in the space effort was not a significant one,” cut the budget request in half; this left Johnson “bitter and hurt.” Even so, by the end of 1962, the council staff had grown to twelve professional staff members, several consultants, and a large support staff; the total staff complement was twenty-eight. This made the council a sizeable element of the executive office of the president, comparable in size to the Office of Science and Technology, which had been created in 1962 to give an organizational foundation for Kennedy’s science adviser Jerome Wiesner and which dealt with all other areas of science and technology. The Space Council budget during the Kennedy administration grew to just over $500,000 per year.6

The main role of the council during the Kennedy administration “was to keep a dialogue going between the people responsible for the military, peaceful and diplomatic uses of space. . . If there was a dispute between any of the Council members and between their agencies, Johnson was to umpire that dispute.” Johnson and the council staff in practice seldom intervened in disputes between operating agencies, especially NASA and the Department of Defense (DOD). In addition to this mediating role, Johnson saw the Space Council as a vehicle for explaining to the American public the importance of the U. S. effort in space; he suggested to Welsh that the council should enlist “the cooperation of the various agencies to produce a series of comprehensive reports to inform the public upon the actualities of the space program.” When Welsh responded, suggesting a series of “Vice President’s Reports on Space,” Johnson’s reaction was “I sure like that. Get on it.” There were fourteen formal meetings of the Space Council during the Kennedy administration, but most were devoted to discussion of already-decided activities, rather than to formulating recommendations for presidential decision or for settling disagreements. During 1962 and early 1963, the council staff devoted a great deal of time and effort to drafting a statement of national space policy, but this initiative was abandoned when both NASA and the Department of Defense opposed issuing such a statement.

In the fall of 1961 Johnson toured a number of space installations, “trying to seek out problems and to boost morale.” Johnson had been advised by his press secretary George Reedy that such a tour “would attract tremendous attention” and “provide a natural basis for a series of reports which would be extremely helpful in informing the public and clarifying the program.” Johnson frequently gave speeches prepared by the Space Council staff on space issues and allowed staff-prepared articles to appear under his name in various publications. At White House breakfasts before presidential

|

|

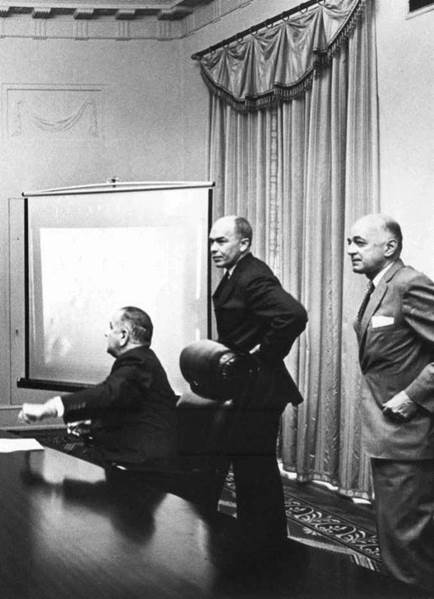

Chairman of the National Aeronautics and Space Council Lyndon Johnson (seated) listens to a space program briefing. Standing are (left) Space Council member and chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission Glenn Seaborg and (right) Space Council executive secretary Edward C. Welsh (NASA photo).

press conferences, Johnson came prepared with responses to potential press questions. The vice president was eager to associate himself with the public attention given to the Mercury astronauts; these occasions “were important to him because they were almost the only times he received national attention and he wanted to keep his name before the public.”7 As Johnson biographer Merle Miller suggests, “the Space Council chairmanship was. . . only briefly satisfying for Lyndon. Once the present program had been evaluated, new directives issued and the revised program set in motion, there was little for him to do.”8

Kennedy’s approach to governance placed heavy responsibility on the line officials in charge of the executive agencies of government; in the case of space, that meant that Kennedy delegated most decision-making authority for the civilian space program to NASA administrator James Webb, and backed Webb up when Webb’s choices were challenged by JFK’s White House advisers. As a veteran of Washington bureaucratic politics and as the head of an agency newly charged with an effort that was a top presidential priority, administrator Webb was insistent on having direct access to the president. Webb was scrupulous in keeping Johnson informed, but he made it clear that he worked for the president, not the vice president. This also left little room for the vice president and the Space Council staff to play a central role in most of the decisions on how best to move forward in sending Americans to the Moon.