Mercury-Redstone 3: A Necessary Success

From the start of Project Mercury in 1958, the project’s plan called for several brief suborbital flights with an astronaut aboard before committing a human to an orbital mission. The first such flight could have come in March 1961 if it had not been for the combination of some relatively minor problems on the January 31 Mercury-Redstone-2 flight carrying the chimpanzee Ham and the biomedical concerns raised by PSAC about an astronaut’s ability to withstand the stresses of spaceflight. An additional test flight without an astronaut (or chimpanzee) aboard was inserted in the Mercury schedule, and the first crewed flight, Mercury/Redstone-3 (MR-3), was slipped until the end of April or early May; to some, that flight seemed rather anticlimactic when Yuri Gagarin orbited the Earth on April 12.

Beginning with the Wiesner task group report in January and extending almost to the day of the flight, there were White House fears that the risks of the MR-3 mission outweighed its benefits. These fears were only amplified by the failure at the Bay of Pigs in mid-April; the possibility that a U. S. astronaut might perish in the full light of the television and other media coverage of the mission so soon after the United States had looked so weak in its unwillingness to support the invasion force it had trained was very troubling to President Kennedy and his top advisers. Sorensen remembers that while “gloating Russians, undecided Third World neutrals, and concerned allies” awaited the outcome of the flight, “untold numbers of the American press insisted for weeks that all their reporters must receive passes to be present.” At the same time, there was insistence that “their editorial writers and columnists must be free to deplore the media circus atmosphere resulting from so many reporters being present.” The White House concern was “that such a big buildup would worsen our national humiliation [the Bay of Pigs] if the flight were a failure.”34

Jerome Wiesner had raised similar concerns as far back as March 9. In a memorandum to McGeorge Bundy, Wiesner expressed his worry about the pressure for live TV and press coverage of the MR-3 launch, fearing that there was a danger of the event tuning into a “Hollywood production” that “could jeopardize the success of the entire mission.” He suggested that the government should meet such pressures “with firmness.” Wiesner on the other hand was concerned about how best to exploit the public relations value of a successful mission to serve administration interests, since “in the imagination of many” the mission would “be viewed in the same category as Columbus’ discovery of the new world.”35 Wiesner’s hope for a historic first was definitively dashed by the Soviet orbital flight in April.

At the March 22 meeting on the NASA budget, President Kennedy had asked about the risks associated with the first Mercury flight. Hugh Dryden assured him that “no unwarranted risks would be involved” and that “the decision to ‘go’ was being made by project managers best qualified to assess the operational hazards.” The PSAC panel on Mercury agreed with this assessment, saying the flight would be “a high risk undertaking but not higher than we are accustomed to taking in other ventures.”36

Still, doubts about the wisdom of going ahead with the mission, at least so soon after the Soviet orbital flight and the Bay of Pigs fiasco, persisted. The person who had led the PSAC review of Mercury, Donald Hornig, on April 18 sent a memorandum to Sorensen raising two questions: (1) “Is MR-3 still justified, in view of the risks, after the Russian flight?” and (2) “If so, should the present schedule be maintained or should it be carried out at a later time?” Hornig noted that after the Gagarin flight “the fact that one human can withstand these conditions [of spaceflight] is now established.” Hornig’s conclusion was that “it seems likely that we should proceed on schedule, particularly since the world already knows that schedule,” but that “our estimate of the risk is still that it cannot presently be demonstrated that the likelihood of disaster is less than one in ten or one in twenty.”37

On April 26, Wiesner told the Space Council’s Welsh that his office had been receiving messages from “some of the scientists whom he knows raising a question about the advisability of our going forward with the Mercury man-in-space shots.” Their concern, said Wiesner, was that “if these shots were successful, they would still look relatively small compared with what the Russians have done, and, if the shots failed, the damage to our prestige would be serious.” In reporting this message to Vice President Johnson, Welsh said that he believed “we should go ahead. . . Having announced that we were going to make the efforts, I believe that we would suffer seriously if we did not go ahead.”38 Concerns about the wisdom of proceeding were not limited to the White House. Senators John Williams (R-DE) and William Fulbright (D-AK) suggested “that the flight should be postponed and then conducted in secret lest it become a well-publicized failure.”39

The MR-3 flight was scheduled to lift off on the morning of May 2. In the preceding days, Ted Sorensen and the president’s brother Robert Kennedy discussed whether it was worse to postpone the flight after the press buildup had reached such a peak or to go ahead with the flight and run the risks of failure.40 President Kennedy made the final decision on whether to go ahead with the flight in an Oval Office meeting on April 29. Present at the meeting were Wiesner, Sorensen, Bundy, and Welsh, among others. One of those present raised the point of “maybe we should postpone the Shepard flight, maybe we shouldn’t take this risk, something might go bad, there might be a casualty, and we’ve had a number of things go rather poorly here and maybe we shouldn’t do this right now.” The majority of the group favored postponing the flight, but Welsh argued that it was no riskier than flying from Washington to Los Angeles in bad weather, and asked the president, “why postpone a success?” According to Welsh, “that ended the discussion.”41 On May 1, the day before the flight was scheduled, James Webb and White House press secretary Pierre Salinger met with Kennedy for a final review of the press arrangements for covering the launch. Webb assured the president that all precautions had been taken and the flight should go forward as scheduled. Kennedy asked his secretary to place a call to NASA’s public information officer in Florida, Paul Haney, to discuss plans for television coverage and to discuss the reliability of the Mercury capsule’s escape system. Salinger talked to Haney from the Oval Office and, after Haney reviewed the history of the launch escape system, told Kennedy that he felt that JFK’s questions had been adequately answered.42

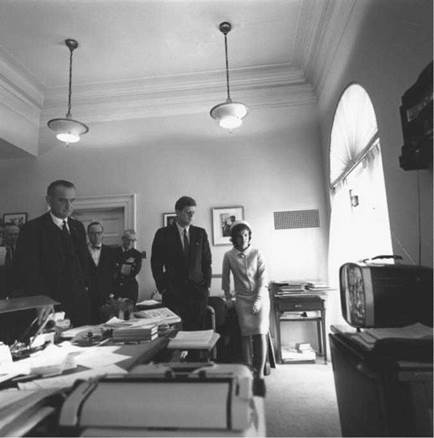

Because of poor weather, the MR-3 flight was postponed on May 2 and again on May 4. Finally, on May 5, astronaut Alan Shepard was launched on what he described as a “pleasant ride.” A wave of national relief and pride over an American success swept the country, from the White House down to the person in the street. At the White House, Kennedy’s secretary Evelyn Lincoln interrupted a National Security Council meeting to tell the president that Shepard was about to be launched. Kennedy, joined by Lyndon Johnson, Robert Kennedy, Robert McNamara, Dean Rusk, Ted Sorensen, McGeorge Bundy, Arthur Schlesinger, and others crowded around a small black and white television set in Lincoln’s office to watch the takeoff. As Jacqueline Kennedy walked by, the president said: “Come in and watch this.” Sorensen suggests that the group watching the flight in Lincoln’s office “heaved a sigh of relief, and cheered” as Shepard and his spacecraft were pulled from the Atlantic Ocean.43 After Shepard was safely aboard the recovery ship, Kennedy called him, saying, “I want to congratulate you very much. We watched you on television, of course, and we are awfully pleased and proud of what you did.”44 The decision to carry out the Shepard flight in full view of the world seems to have paid off. A May 1961 report of the U. S. Information Agency comparing international reactions to the Gagarin and Shepard flights noted that in terms of public reaction “the U. S. reaped a significant psychological advantage over the Soviet Union.” This was due in large part to the “openness” surrounding the Shepard flight, plus the flight’s “technological refinements and the poise and humility of the U. S. astronaut.” People around the world contrasted this “critically to Soviet secrecy and blatant propaganda exploitation, as well as the obviously politically controlled behavior of Gagarin.” The report went on to say that “without question the greatest impact on expressed opinion in the Free World was made by the openness of the U. S. both as to the flight itself and to the release of scientific information.” In contrast, “Soviet secrecy was deplored and even continued to

|

President Kennedy in his secretary’s office watching the May 5, 1961, launch of the first U. S. astronaut, Alan Shepard. Also visible are Vice President Lyndon Johnson, national security adviser McGeorge Bundy (over Johnson’s right shoulder), presidential assistant Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. (in bowtie), chief of Naval operations Admiral Arleigh Burke, and Jacqueline Kennedy (JFK Library photograph). |

arouse some skepticism.” Some of the commentary “showed a significant tendency to identify itself with the U. S. success.”45

If the Shepard flight had been a catastrophic failure, it is very unlikely that President Kennedy would have, or politically could have, soon afterward set as a national goal the flight of Americans to the Moon. However, the unqualified success of the flight in both technical and political terms likely swept away any of Kennedy’s lingering reservations with respect to the benefits of an accelerated space effort with human space flights as its centerpiece. In a formal statement issued after the flight, Kennedy said: “All America rejoices in this successful flight of Astronaut Shepard. This is an historic milestone in our own exploration into space. But America still needs to work with the utmost speed and vigor in the further development of our space program. Today’s flight should provide incentive to everyone in our nation concerned with this program to redouble their efforts in this vital field. Important scientific material has been obtained during this flight and this will be made available to the world’s scientific community.” At a press conference later in the day, Kennedy announced that he planned to undertake “a substantially larger effort in space.”46