Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson Leads. Space Program Review

It had been assumed since the March meetings on the NASA budget that Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson as the new chairman of the National Aeronautics and Space Council would, once he formally assumed that position, lead a comprehensive review of the U. S. space program that would provide the basis for decisions in fall 1961 on the future of that program, and especially the future of the human space flight effort. But the events of April 1961 drastically shortened the time allotted to that review. Johnson did not attend the April 14 White House meetings on the space program. He was returning from his first overseas trip as vice president, to the West African nation of Senegal, which was celebrating the first anniversary of its independence from France, with stops in Geneva and Paris on the way home. But on April 19, after President Kennedy had in the early hours of the day walked disconsolately with Ted Sorensen and then alone on the south lawn of the White House in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs failure, he met later in the day with Lyndon Johnson and James Webb to discuss the organization of the accelerated review he had decided was needed. Johnson suggested that he would “have hearings, lay a background and create a platform for a recommendation to Congress.” He asked Kennedy to give him a memorandum “that would provide a charter for those hearings” and would be an “outline of what concerned him.”29

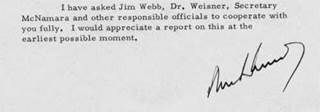

Ted Sorensen drafted a one-page memorandum, and President Kennedy signed it and sent it to Johnson the next day, April 20. The memorandum stands as a historic document; it spelled out the requirements that led directly to the decision to go to the Moon as the centerpiece of an accelerated U. S. space effort. It said:

In accordance with our conversation I would like for you as Chairman of the Space Council to be in charge of making an overall survey of where we stand in space.

1. Do we have a chance of beating the Soviets by putting a laboratory in space, or by a trip around the moon, or by a rocket to land on the moon, or by a rocket to go to the moon and back with a man. Is there any other space program which promises dramatic results in which we could win?

2. How much additional would it cost?

3. Are we working 24 hours a day on existing programs? If not, why not? If not, will you make recommendations to me as to how work can be speeded up.

4. In building large boosters should we put our emphasis on nuclear, chemical, or liquid fuel, or a combination of these?

5. Are we making maximum effort? Are we achieving necessary results? [1]

THE WHITE HOUSE

WASHINGTON

April 20, 1961

MEMORANDUM FOR

VICE PRESIDENT

In accordance with our conversation I would like for you as Chairman of the Space Council to be in charge of making an overall survey of where we stand in space.

1. Do we have a chance of beating the Soviets by putting a laboratory in space, or by a trip around the moon, or by a rocket to land on the moon, or by a rocket to go to the moon and back with a man. Is there any other space program which promises dramatic results in which we could win?

2. How much additional would it cost?

3. Are we working 24 hours a day on existing programs. If not, why not? If not, will you make recommendations to me as to how work can be speeded up.

4. In building large boosters should we put out emphasis on nuclear, chemical or liquid fuel, or a combination of these three?

5. Are we making maximum effort? Are we achieving necessary results?

|

|

The April 20, 1961, memorandum that led to the decision to go to the Moon (LBJ Library image).

The Kennedy memorandum both contained a very clear statement of a requirement—“a space program which promises dramatic results in which we could win”—and a sense of urgency. Kennedy wanted Johnson’s report “at the earliest possible moment.” Budget director Bell suggests that “the President would not have made such a request unless he expected a positive answer and a strong program, and therefore he was pretty sure before he made that request that that was what he intended to do.” At an April 21 press conference, Kennedy was asked: “Mr. President, you don’t seem to be pushing the space program nearly as energetically now as you suggested during the campaign that you thought it should be pushed. In view of the feeling of many people in this country that we must do everything we can to catch up with the Russians as soon as possible, do you anticipate applying any sort of crash program?” Kennedy replied:

We are attempting to make a determination as to which program offers the best hope before we embark on it, because you may commit a relatively small sum of money now for a result in 1967, ‘68, or ‘69, which will cost you billions of dollars, and therefore the Congress passed yesterday the bill providing for a Space Council which will be chaired by the Vice President. We are attempting to make a determination as to which of these various proposals offers the best hope. When that determination is made we will then make a recommendation to the Congress.

In addition, we have to consider whether there is any program now, regardless of its cost, which offers us hope of being pioneers in a project. It is possible to spend billions of dollars in this project in space to the detriment of other programs and still not be successful. We are behind, as I said before, in large boosters.

We have to make a determination whether there is any effort we could make in time or money which could put us first in any new area. Now, I don’t want to start spending the kind of money that I am talking about without making a determination based on careful scientific judgment as to whether a real success can be achieved, or whether because we are so far behind now in this particular race we are going to be second in this decade.

So I would say to you that it’s a matter of great concern, but I think before we break through and begin a program which would not reach a completion, as you know, until the end of this decade—for example, trips to the moon, maybe 10 years off, maybe a little less, but are quite far away and involve, as I say, enormous sums—I don’t think we ought to rush into it and begin them until we really know where we are going to end up. And that study is now being undertaken under the direction of the Vice President.

Then, for the first time in public, Kennedy said: “If we can get to the moon before the Russians, then we should.”30