Richard Nixon Meets the Space Shuttle

John Ehrlichman joined the president for the meeting with Fletcher and Low. Fletcher had suggested that Peter Flanigan also be at the meeting, given his important role in the shuttle decision, but Flanigan was not present. As the two NASA officials waited to enter the president’s office with a shuttle model, Ehrlichman asked whether it was the NASA shuttle or the OMB shuttle. Low’s reply was “it is the United States’ shuttle.”24

Ehrlichman took detailed notes during the meeting; there was no taping system in Nixon’s San Clemente office. Several days later, George Low

|

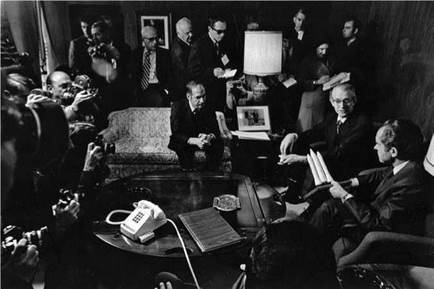

Press photographers and reporters capture the moment as NASA’s Jim Fletcher and George Low show President Nixon a model of the space shuttle in the president’s San Clemente, California, office on January 5, 1972. The top of John Ehrlichman’s head is in the foreground. (Photograph WHPO 8172-4, courtesy of Richard Nixon Presidential Library & Museum) |

also prepared a “memorandum for the record” regarding the meeting and discussed it in one of his “personal notes.” Ehrlichman also prepared a “Memorandum for the President’s File” summarizing the meeting. So there is a good record of what transpired as the meeting stretched from its scheduled 15 minutes to over half an hour. Low reported that “it soon became apparent that he [Nixon] was interested in the shuttle and in the space program as a whole and wanted to spend more time with us. The discussion was warm, friendly, and productive.”

First, reporters and press photographers were briefly present to see Fletcher present the shuttle model to President Nixon. After they left, the first order of business was whether to adopt Space Clipper as the new name for the shuttle program. Nixon decided to defer the decision to a later time; this led to a rapid modification of the planned presidential statement to remove any mention of the Space Clipper designation. (The name of course was never changed—space shuttle it would remain.) Nixon asked if the shuttle was really worth a $7 billion investment. Fletcher and Low replied in the affirmative. Fletcher said that the shuttle was a necessary step to future space exploration, that it was too expensive to explore and do other things in space using existing launchers, that the shuttle was useful for military purposes such as a “sudden need” and interception and inspection of others’ satellites, and that it was part of the “new frontiers of the mind” with “unpredictable” impacts. Fletcher also mentioned speculative future uses of the shuttle such as facilitating solar power from space and nuclear waste disposal; Nixon’s reaction was that “these kinds of things tend to happen much more quickly than we now expect and that we should not hesitate to talk about them now.” Nixon observed that the shuttle would “open up entirely new fields” and was not a “$7 billion toy,” since it would “cut operations costs by a factor of 10.” He added that even if the shuttle “were not a good investment, we would have to do it anyway, because space flight is here to stay. Men are flying in space now and will continue to fly in space, and we’d best be a part of it.” The president was very interested in the status of planning for a docking between U. S. and Soviet spacecraft, and suggested that Ehrlichman ask Henry Kissinger to be sure to add a discussion of that possibility to the draft agenda for the May 1972 U. S.-Soviet summit meeting in Moscow.

Ehrlichman’s brief summary of the meeting said: “After the press and photographers left the NASA representatives explained the Shuttle to the President and the President asked questions about the Russian rendezvous, the Sky Lab, the use of solar power, the recent AEC [Atomic Energy Commission] proposal for the disposal of waste in space and other technical matters.” Low recorded that Nixon told him and Fletcher that NASA “should stress civilian applications but not to the exclusion of military applications.” However, Ehrlichman’s notes say that Nixon’s guidance was to “downplay” the shuttle’s military aspects, particularly in the context of future international cooperation. Nixon stressed that from the start of his presidency he had “an interest in international peaceful applications of space programs.” Low records Nixon as saying that “he was disappointed that we had been unable to fly foreign astronauts on Apollo. . . He understood that foreign astronauts of all nations could fly on the shuttle and appeared to be particularly interested in Eastern European participation in the flight program.” Nixon was “not only interested in flying foreign astronauts, but also in other types of meaningful participation.” Fletcher told Nixon that the shuttle program would have a “big job impact,” with 3,500 jobs in 1972, 14,000 by 1973, and 50,000 at its peak. (Commenting on a draft of Low’s memorandum for the record regarding the meeting, Fletcher noted that the president “wanted to be sure that aerospace employment was mentioned, particularly on [the] West Coast.” But Fletcher thought that because of the political sensitivity of Nixon’s indicating in the meeting that the shuttle prime contract should go to a California company, Low should not mention this interest in his memorandum.) Nixon stressed that it was his view that the United States needed to be “No. 1” in all fields of space activity. “Like the new world,” he said, “someone will explore.” And it was important for the United States to be in the vanguard.25

Ehrlichman commented on “Nixon’s fascination with the [shuttle] model. He held it and, in fact, I wasn’t sure Fletcher was going to be able to get it away from him” when the meeting was over. Actually, Fletcher and Low left the model behind for possible display in Nixon’s White House office.26

After the meeting was concluded, the White House press office issued the presidential statement, quickly revised to delete any mention of Space

Clipper. In contrast to John Kennedy’s high-profile speech before a joint session of Congress announcing his decision to go to the Moon, Richard Nixon did not speak to the press about his shuttle decision. In the statement, which based on a draft prepared by Bill Anders, Nixon declared “I have decided was today that the United States should proceed at once with the development of an entirely new type of space transportation system designed to help transform the space frontier of the 1970’s into familiar territory.” The statement added “the space shuttle will give us routine access to space by sharply reducing costs in dollars and preparation time. . . Most of the new system will be recovered and used again and again—up to 100 times. The resulting economies may bring operating costs down to as low as one-tenth of those for present launch vehicles.” The shuttle would “take the place of all present launch vehicles except the very smallest and the very largest.” It suggested that “we can have the shuttle in manned flight by 1978, and operational a short time later.” The space shuttle, the statement suggested, “will revolutionize transportation into near space by routinizing it. It will take the astronomical costs out of astronautics.”27

There were a number of loose ends to tie up over the next two months before NASA would be ready to announce the final configuration of the space shuttle and invite aerospace firms to bid on a contract to develop it. In particular, the choice of how the shuttle orbiter would be boosted off the launch pad had not been made; both liquid-fueled and solid-fueled boosters remained in contention. But with his January 5, 1972, statement, President Richard Nixon had formally approved the space shuttle program; the shuttle would be the centerpiece of U. S. human space flight activities for the next four decades.