Final Flax Committee Meeting

To that end, Low and Dale Myers met with Flax on November 12, in advance of the November 17-18 meeting of Flax’s committee. It was still Flax’s view that “the next manned space flight program should involve some technological advance and that operational costs are not all that important,” since whatever system was chosen would not be flown frequently. Throughout the shuttle decision process, neither NASA nor the White House and its external advisors gave careful attention to how much it would cost to operate the shuttle; this would turn out to be the program’s Achilles heel. Flax also suggested “that it is Ed David’s view that the shuttle is dead unless David saves it and that the only way he can save it for us is by supporting something that is much less than the previously proposed shuttle; namely, the glider.”

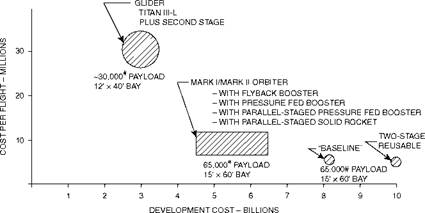

Low by this point had developed a diagram showing a cost curve that compared the development and operating costs of various shuttle designs and the space glider; he was to use a version of that diagram and the trade-off between development and operational costs it depicted as a major selling tool in his frequent meetings during November and December. He drew the curve on Flax’s blackboard and made the point that NASA “now had some very interesting developments in the range of development costs between $4.5 billion and $6 billion, with operating costs around $10 million per flight.” Flax thought that “some” of his committee members might be willing to support a shuttle with those characteristics, and Low and Myers agreed that Myers would present, for the first time, “the small orbiter, together with the parallel-staged pressure-fed booster” at the November 17 Flax committee meeting. This would be the first time the TAOS configuration, the shuttle design ultimately selected, would be briefed to anyone outside of NASA. Low agreed to come to the second day of the committee’s meeting to make the point that “we can buy the kind of shuttle that we are now proposing within a reasonable total NASA budget, while still at the same time having a strong science and applications program.”28

Before the Flax committee meeting Low also interacted with committee members Fubini and Lewis Branscomb. He found Fubini “on the side of a small glider” on the grounds that “the United States should be satisfied with two or three flights per year. He sees no need for routine operations with men.” That perspective, thought Low, “strongly reflects Ed David’s view.” By contrast, Branscomb was “very much on the other side,” believing that “the United States needs routine operations, and to get these it needs a new recoverable space transportation system.” Branscomb didn’t care “whether or not men are on board, but. . . NASA has told a convincing story that men should be on board.” In connection with the Flax committee session, Low also met with DOD’s Johnny Foster, who had been charged with developing a statement of the rationale behind DOD as well as NASA support of the shuttle, only to discover that “Foster had not yet made up his mind on the value of the shuttle” because it was not a response to “the hiatus in United States space activity during a time that the Soviet Union was bound to have major demonstrable advances in their space flights.” Low’s counterargument was that “having the shuttle well under development and on the horizon. . . will be a far better position to be in than not having anything to show for the future.” He added “once the shuttle is available, we ought to be able to whip the pants off anybody that does not have this kind of a quick reaction, routine capability.” Given his own ambivalence, Foster had made no progress in developing the shuttle rationale statement that NASA and DOD a month earlier had agreed to prepare.29

As Low attended the second day of the Flax committee meeting on November 18, he drew his operations costs versus development costs curve on the blackboard to make the point that “over the past six months the shuttle has become a much more reasonable vehicle in terms of development costs,” since NASA was “now focusing on a shuttle that will cost between $5 and $6 billion to develop” and from $6-1/2 to $12 million to operate. Low argued that the “smaller, and much lower in development costs, glider should not be considered because it will be so terribly expensive to operate.” The main questions, he suggested, were “whether the shuttle should be small or large and whether it should provide for routine operations or one or two flights per year.” Low thought that most committee members understood his argument, “but if a vote had been taken right then, they would have still voted for the small glider simply because they don’t believe in routine space flight operations.”30

|

SPACE SHUTTLE COST COMPARISON

The development cost versus operating cost curve developed by George Low in fall 1971 as he attempted to gain White House support for the shuttle. What is designated as the “baseline” shuttle in this diagram is a two-stage shuttle with expendable hydrogen tanks mounted next to the shuttle orbiter’s fuselage. (Diagram courtesy of Dennis Jenkins) |

This was the final meeting of the Flax committee, and the group never issued a formal report. Perhaps the committee’s most significant contribution was crystallizing the central issue in the shuttle debate. By this point, there was agreement that some new space transportation system was needed. The committee’s deliberations focused attention on the basic issue of whether that system would include a full capability vehicle capable of launching all U. S. payloads on a routine basis or a smaller vehicle, either a powered shuttle or a glider, to be flown occasionally to test various technologies while also keeping a U. S. program of human space flight alive. As the Flax committee met for the last time, that question remained very much undecided.