Safe Return

Splashdown was set for just after 1:00 p. m. on the afternoon of April 17. Haldeman gives a vivid description of the events of the day:

Apollo 13 day. They made it back and the P [President Nixon] was really elated! Started out in the morning with some general details, then into a lot of planning, etc., for his participation in the Apollo return. Had TV, squawk box, and [former astronauts] Collins and Anders set up in Alex’s [Nixon aide Alexander Butterfield] office to keep him posted. Kind of anxious about results but basically confident that they’d make it, and all wrapped up on little specifics about the trip, which we have very well set up on contingency basis.

[material deleted]

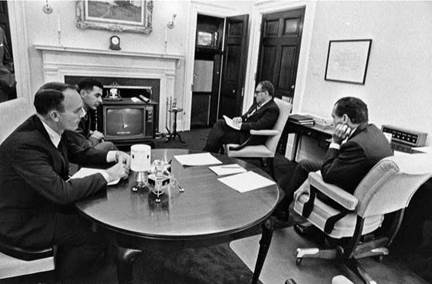

For splashdown, P watched in Alex Butterfield’s office with Alex, me, Anders, Collins and K [Henry Kissinger]. Was very cranked up. Ordered cigars for all on success when learned that was Chris Kraft tradition at NASA. Put through call to wives immediately, then waited to call astronauts till they were aboard Iwo Jima [the recovery aircraft carrier] and had called wives. Meanwhile P called all the Congressional leaders and George Meany, saying to all, “Isn’t this a great day.” He was really excited. . . Then talked to astronauts and told them of trip plans, then out to press to do likewise, then over to the EOB [Executive Office Building] at about 3:30, with no lunch. Took a nap.

Nixon biographer Richard Reeves adds an additional detail to the day’s account. He suggests that as Nixon talked to the Congressional leaders after the splashdown, he was “having one drink after another,” and that soon after he reached his hideaway office in the Executive Office Building, “the President was drunk, falling asleep on the couch.” If that were indeed the

|

Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins (foreground) and Space Council Executive Secretary Bill Anders join President Nixon and Henry Kissinger to watch as the Apollo 13 command module parachutes to a safe return. (National Archives photo WHPO 3359-7A) |

case, Nixon recovered quickly; that evening he hosted a White House performance by country music singer Johnny Cash.28

On April 18, President Nixon flew to Houston. At the Manned Spacecraft Center, he presented the Medal of Freedom to the Apollo 13 mission operations team. Then he flew to Hickham Air Force Base in Honolulu, Hawaii. There he presented the Medal of Freedom to Lovell, Haise, and Swigert. He told the crew that “this was a successful mission, a great mission on behalf of your country. . . You did not reach the moon, but you reached the hearts of millions of people on earth by what you did. . . We realize that greatness comes not simply in triumph, but in adversity.”29

Richard Nixon’s associates never passed up an opportunity to portray the president in a positive light. Even as they planned how the president would deal with the unfolding crisis, they made sure that his involvement would reflect well on Nixon as a national leader. In the days after the safe return of the Apollo 13 crew, the White House approached Life magazine senior correspondent Hugh Sidey about “doing an inside story on the President’s involvement in and the attitudes, etc. during the Apollo 13 crisis.” It took several months for this suggestion to bear fruit, but eventually Sidey wrote a very positive account, saying that “the near tragedy of Apollo 13, a deeply emotional drama for all Americans, was even more so for the President.” The Apollo astronauts, Sidey suggested, were an “obsession” for Nixon, who viewed them “as more than heroes.” According to Sidey, Nixon, “in his single-minded manner. . . seems to be trying to assess and grasp the spirit of the astronauts.”30

Richard Nixon’s involvement with Apollo 13 has been discussed in some detail because the episode reinforced to his associates the reality that Nixon would never accept a future U. S. space program not including human space flight as an important element. In addition, Nixon’s concern for the astronauts’ safety became linked to a political calculus in his mind regarding possible negative political fallout from a similar problem on a future Apollo flight. When he got the impression that Apollo 17 was particularly risky, it is not surprising that Nixon’s first instinct was to cancel the flight.